Latest

Not Worth the Paper They Were Printed On

Louisiana’s state debt default of 1843

Published: May 23, 2023

Last Updated: May 25, 2023

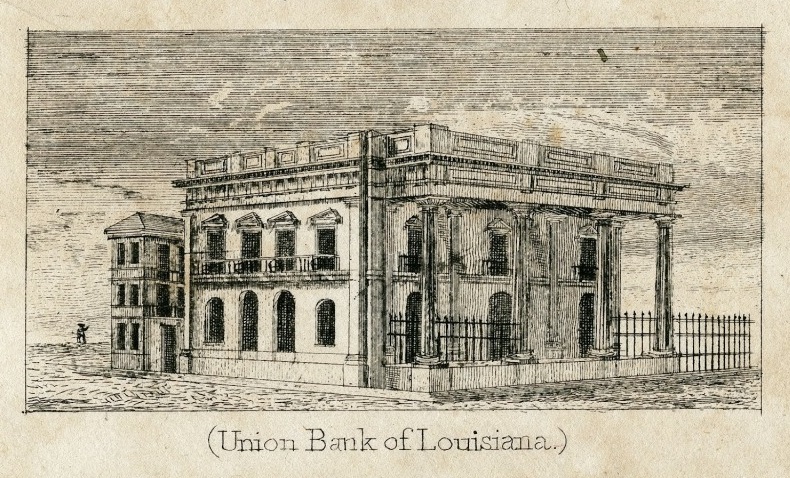

Print by William Lemuel Greene, The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Union Bank of Louisiana, ca. 1835.

Editor’s Note: At this article’s publication in late May 2023, negotiators persist in their attempts to reach an agreement that will raise the federal debt ceiling and allow the United States government to continue issuing debt to fund its operations. All sides have emphasized that the United States has never defaulted on its debt, and academics and policymakers generally agree that to do so risks enormous financial consequences. While the federal government has never defaulted, individual states have failed to honor debts their governments incurred: Arkansas during the Great Depression, Confederate state governments after their defeat in the Civil War, and a group of states caught in the turmoil following the financial panic of 1837. Louisiana was among these, defaulting on its obligations in February 1843.

Most of us know the story of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, published in December 1843 and set in nineteenth-century London. Ebenezer Scrooge, through the visits of three ghosts, comes to appreciate the true meaning of Christmas and the value of family, friendship, and love. Missing from the many film adaptations—but present in the text itself—is a subtle, yet poignant, financial reference. In one critical scene, Scrooge has a dream, a nightmare in fact, in which he sleeps through an entire day thereby rendering his investments so worthless to be but a mere “United States security.” The reference was abundantly clear to those who followed international finance. While the United States had briefly paid off its national debt in full within the past decade, the financial infidelities of specific states had become a story of global concern. By 1843 American states faced a significant debt problem—perhaps none more so than Louisiana.The United States underwent significant economic expansion in the 1820s and 1830s. Americans moved across the Appalachian Mountains to farm on fertile soil, reaching into the American South as cotton and sugar cultivation took hold. New Orleans proved pivotal to this growth. Cotton’s emergence and the related increase in credit demand led to the creation in several southern states of “property banks,” state-chartered banking institutions that collateralized plantations and the enslaved persons who worked them. Various states engineered state-backed mortgage bonds that accepted plantations and enslaved persons as collateral to help planters finance an expansion of their enslaved-centric businesses. In other words, these banks directly helped to expand slavery.

Perhaps no state demonstrated this operation so clearly and on such a large scale as Louisiana. Louisiana chartered three property banks between 1827 and 1833, all based in New Orleans: the Consolidated Association of the Planters of Louisiana (CAPL), chartered with capital of $2.5 million; Union Bank, with $7 million; and Citizens Bank, with $12 million. These reflected a new form of banking in the South, referred to by one contemporary as a combination of a “state loan office and an ordinary banking institution.”

CAPL, the first of these banks, received a charter in March 1827. Planters in Louisiana mortgaged their plantations and enslaved persons to become shareholders in CAPL. Once done, these planters could borrow from the bank up to 50 percent of their property value in the form of local CAPL banknotes. These banknotes were supported by a line of credit from Barings Bank in London. In return, Barings issued bonds (sent to them by CAPL) to sell to clients in Europe to cover the credit line. These 5 percent interest bearing bonds came in denominations of $500 and $1,000. Finally, and perhaps most crucially, while CAPL operated as a private bank, the bonds it issued were backed by the State of Louisiana, which acted as a guarantor against mortgages on property. As highlighted by historian Ed Baptist in his 2014 book The Half Has Never Been Told, the purchase of a CAPL bond reflected “really the purchase of a completely commodified slave: not a particular individual, but a tiny percentage of the income flows derived from each one of thousands of slaves. The investor, of course, escaped the risk inherent in owning an individual slave, who might die, run away, or become rebellious.”

The 1832 charter of the Union Bank as well as the Citizens Bank largely operated under the same mechanisms. The fact that Louisiana secured these loans eased the concern of many investors and led to widespread investment across the Atlantic. Because a relatively small percentage of people in the state were tax-paying citizens relative to the enslaved population, and slavery was central to Louisiana’s economy, no American state relied on foreign capital as much as Louisiana. These state-issued bonds found wild success in London, Paris, Amsterdam, and beyond.

American state debt increased in the aftermath of the Panic of 1837. A perfect storm of depressed cotton prices, a real estate bubble, restrictive lending policies in Great Britain, and speculative lending practices aligned to create a transatlantic financial panic. This fiscal anxiety ushered in a depression lasting into the middle part of the 1840s. Many American states looked to Europe to pursue new lines of capital during the depression. However, the Panic of 1837 and its subsequent fallout proved to be one of the first real challenges for European investors in American indebtedness. Many of the European banks remained concerned regarding the financial situation across the Atlantic and its potential impact on their own portfolios and those of their clients, but a vibrant market for these bonds remained. A flurry of debt sales abroad in the late 1830s meant states faced interest payments they could not make without significant changes to their revenue streams. The debt issuance had reached stratospheric levels. These Louisiana bonds acted as part of a larger US state debt issuance that, by 1840, reached more than $170 million.

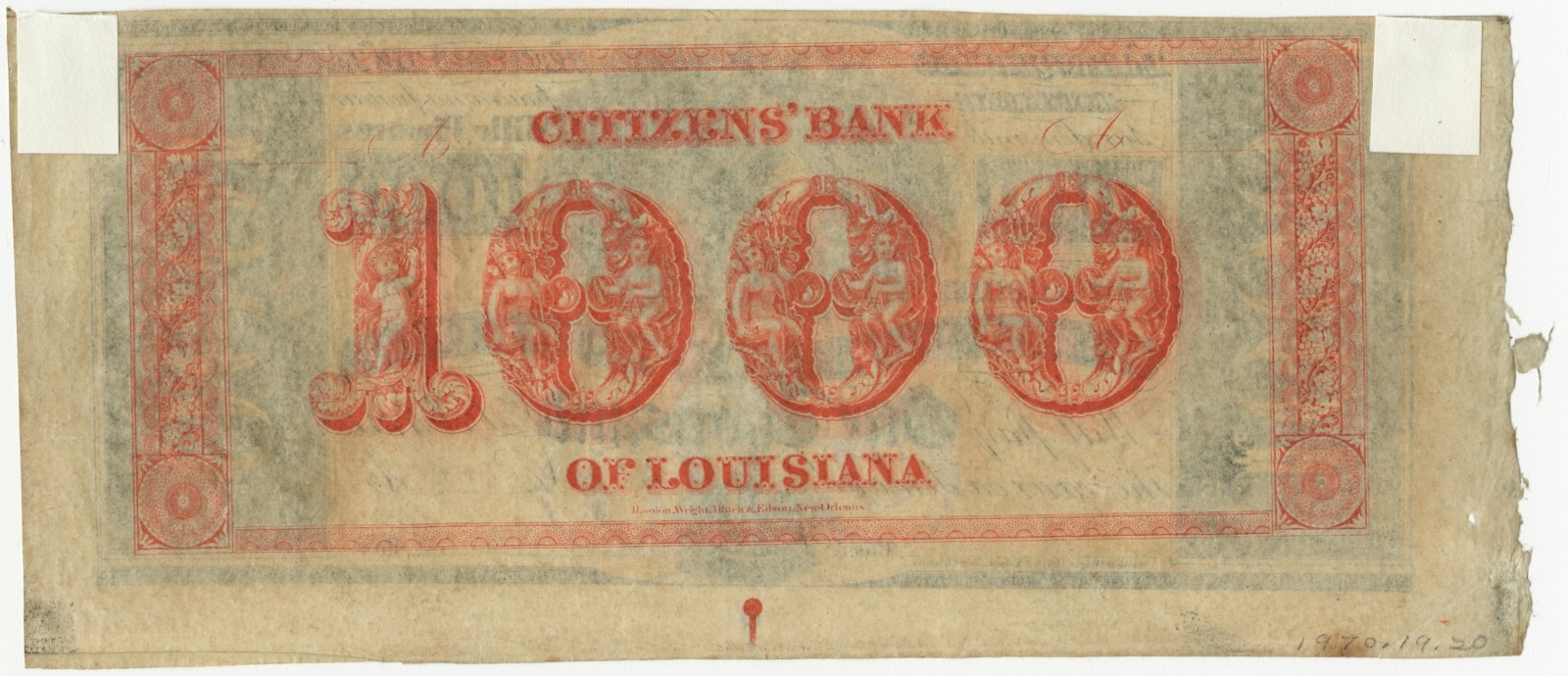

A one-thousand-dollar note issued by Citizens Bank of Louisiana, ca. 1840 (recto). The Historic New Orleans Collection.

But then it came crashing down. Overextended states could no longer make their interest payments to creditors, and legislatures refused to address the issue by taking actions such as raising sufficient taxes. These facts only complicated matters. What happened afterwards troubled investors within the United States and abroad. Eight US states and one future state (the Territory of Florida) defaulted on their debts while another five states barely avoided default.

In February 1843, Louisiana became one of the eight states to formally default.

The issues of financial infidelity on the part of various states through default in both the North and South hit property banks hard. The prominent banking journal Circular to Bankers claimed that Louisiana tended to be “politic and wise in borrowing,” and Barings circulated a glowing bond prospectus—but the reality was something entirely different. Louisiana’s tax revenue in the late 1820s amounted to only $263,000 (roughly $8 million in today’s money), a sum that could barely cover the government’s expenditures. By comparison, in the same period, the State of Pennsylvania had government expenditures of approximately $6 million that it also serviced with large amounts of debt alongside tax revenue. The tax base in Louisiana remained small; the 1830 census placed the overall population at 215,739 (of whom more than 50 percent were enslaved persons and therefore not tax-paying citizens.)

Despite what appeared to be critical issues in financing their debt, the legislature continued to permit the sale of bonds—amounting to $21 million by 1841. By the fall of 1839, however, all but one New Orleans bank suspended specie payment (the payment of hard coin or “specie” in exchange for bank notes) in the wake of the Panic of 1837. Internal bank controls that encouraged independent audits affirmed the supposed stability of Louisiana property banks through the 1830s, even during the early troubled days following the Panic of 1837. A state commissioner of currency, in conjunction with a board of bank presidents, likewise asserted this stability.

In his 1840 annual message, Governor Andre Bienvenu Roman of Louisiana recommended that smaller banks liquidate and blamed the financial situation on the banks’ increasing circulation (both of bank notes and bonds) beyond their means. The legislature paid no heed to Governor Roman, declining to push weaker and more vulnerable banks to liquidate. Instead, they passed new legislation authorizing additional bond issues, which increased the state’s liability should the banks fail to honor their payments. The hope was that new bond sales overseas could generate enough revenue for the banks to cover the previous bond issues. Roman vetoed virtually every single measure. A year later Governor Roman again tried to emphasize the state’s dire financial situation, but the legislature refused to act. Yet Roman continued to emphasize that Louisiana would honor its debts. According to Roman, “the honor of the people will be prompted by that very difficulty to observe conscientiously and religiously its pledged faith.”

Roman’s successor, however, put Louisiana on the path to default. Alexandre Mouton, a Democrat, had disdain for virtually all banks and played a key role in the state legislature passing a law in April 1843 that withdrew guaranteed state backing for bonds. Mouton knew the state could not cover more than $1.2 million in interest payments that the banks had failed to cover themselves and, in fact, the government of Louisiana exceeded its income at the time by more than $200,000 per year. The legislation that shifted “shares” into “certificates” of the banks that the state no longer guaranteed also permitted banks such as the CAPL (without consultation with bondholders) to extend their bond terms by fifteen years with the option to extend them even further.

The legislation led to a revolt by foreign bondholders and their banks. Barings Bank issued a circular to CAPL’s foreign creditors in April 1843 noting that the state of Louisiana failed to provide more than $750,000 (roughly $32 million in today’s money) owed Barings for the state bonds of June 30 as well as the interest payments on the same day. “The recent conduct of the legislature,” stated the circular, “has had the effect of embarrassing the banks, of depreciating the value of their assets, of lowering the credit of the state, and by the non-payment of the interest or capital of the bonds of greatly depreciating the prices of these securities.”

A one-thousand-dollar note issued by Citizens Bank of Louisiana, ca. 1840 (verso). The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Barings worked with other financial entities to “right” the financial path of this debt-laden state. Barings began an active campaign in Louisiana with op-eds in both French and English explaining the risks residents would face if the state did not honor its debts. Barings did not act alone; Hope & Co. of Amsterdam also presented a petition to the state legislature on behalf of Citizens Bank bond holders.

The end of property banks closed in. While the banks grew insolvent over the course of 1842, they did not disappear overnight. CAPL and Citizens Bank both operated as different banking entities known as liquidating banks until 1882 and 1902, respectively. Union Bank converted into a regular stock bank prior to the Civil War. But the days of property banks in Louisiana ended.

Such a far-fetched financial scheme backed by the state would not be sustained. While these property banks engendered much good will from the 1820s into the late 1830s as they assisted wealthy white landowners to expand slavery in Louisiana, such a financial system could not be maintained. Both sugar and cotton planters inflated their assets to gain increasing access to capital without necessarily the means to make payment back to the banks. Furthermore, the banks themselves did little to curtail this asset inflation, thereby exacerbating the problem. Even before the Panic of 1837, the stability of these institutions had been questioned, and the state’s lack of relative oversight ultimately came home to roost.

The defaults sparked a credit crisis throughout the United States. London financier and American expatriate George Peabody (himself kicked out of a London social club because of American debt defaults) succinctly proclaimed, “As long as there is one state in the Union in default no U.S. Government bonds can be negotiated.” American attempts to contract a federal loan abroad in 1842 and 1843 were firmly rebuffed in London, Paris, and Amsterdam. The American representative on the credit mission dejectedly reported to Washington, “The condition of American credit in Europe is a source of deep humiliation to every American who visits that section of the world.”

Regarding Pennsylvania, Sydney Smith, the canon of St. Paul’s Cathedral, perhaps shared the sentiments of many when he stated, in what effectively amounted to a letter to the editor, how he “never met a Pennsylvanian at a London dinner without feeling a disposition to seize and divide him.”

As the 1840s progressed, most but not all American states slowly resumed their debt payments. That included Louisiana, which performed a legislative about face in 1844 on its debt commitments. States implemented new forms of taxation alongside spending cuts. They also expedited the implementation of previously authorized taxes, and accelerated land sales with favorable terms for buyers to increase revenue in the short term.

Undoubtedly the financial world has changed drastically since the 1840s. Yet the state default sagas from this period offer an interesting parallel to the threat of federal debt default in 2023. A default in today’s America would likewise lead to market turmoil and a lack of credit access from foreign investors—an eerie reminder of the international ramifications of default for US public credit and standing on a global stage. As debt negotiations heat up, the financial legacy of Louisiana and a multitude of other states from the antebellum period offer a stark warning on the dangers of default.

David K. Thomson is an associate professor of history at Sacred Heart University and the author of Bonds of War: How Civil War Financial Agents Sold the World on the Union (University of North Carolina Press, 2022).