Nueva New Orleans

The role of Latino/as in rebuilding New Orleans

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photo by Cheryl Gerber.

Clean-up workers for Hurricane Katrina clean out Tulane University's School of Tropical Medicine on Canal Street in New Orleans, October 5, 2005.

New Orleans’ location on the Mississippi River and its access to the Gulf of Mexico made the city a major port with strong ties to Central America and the Caribbean, especially with Cuba. In 1778, the first group of Isleños, from the Canary Islands, settled in the area, and more continued to arrive until 1783. Gálvez was then governor and provided housing and financial subsidies from the Spanish government. Los Isleños became self-sustaining in St. Bernard Parish, due to their hard work in fishing, fur trapping, and hunting, and many of their descendants continue to live in the New Orleans area. New Orleans was home to the nation’s first Spanish-language newspaper, El Misisipi, which began publishing in 1808 and was mostly written for Spanish colonials who had remained after the Louisiana Purchase.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Latin Americans began arriving, mostly due to trade between New Orleans and Central American fruit companies, especially ones in Honduras. The migration of Latino/as increased in the 1960s as some sought refuge from dictatorial regimes while others pursued better economic opportunities. For many years, New Orleans was known as the Gateway to the Americas. In recognition of the bonds between New Orleans and Latin America, Mayor Chep Morrison conceived the Latin American corridor on Basin Street, with monuments erected between 1957 and 1966 to three Latin American heroes: Venezuelan military and political leader Simón Bolívar; Mexican president Benito Juárez; and Honduran political leader Francisco Morazán. As other cities competed for trade and tourism, New Orleans lost its gateway status, and many of the Latin American consulates in the city closed between 1980 and 2000.

Menu board at Taqueria Guerrero, one of two Latin American restaurants to open in the same Mid-City block after Hurricane Katrina. Photo by Zack Smith

Nevertheless, unlike other cities where Latino/as are concentrated in particular neighborhoods, or barrios, New Orleans had and still has a heterogeneous Central American population scattered throughout different neighborhoods. Hondurans make up the majority of the Central American population in New Orleans and constitute the largest Honduran community in the United States; Mexicans, Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Cubans are other significant groups that make up the Latino/a community. The 2000 Census registered 58,545 Latino/as in the New Orleans area, with most living in Kenner, followed by Mid-City and the West Bank.

When I arrived in New Orleans in 1979, there were few Latin American restaurants. My family and I frequented the legendary Cuban restaurant Liborio in the Central Business District, owned by the Cortizas family, and shopped at Union Supermarket in Mid-City. The growth of the Latino/a population after Hurricane Katrina brought about a significant increase in the array of available Latin American food products in local supermarkets, as well as a surge in typical Latin American restaurants across various neighborhoods.

In the aftermath of Katrina, Latino/as moved to New Orleans in record numbers to work in rebuilding the city. Men and women, documented and undocumented, came from Mexico, Central America, and Brazil, as well as from other cities in the United States. The federal government suspended many labor regulations in order to speed up the city’s recovery, and workers lived in terrible conditions—some in abandoned buildings, others in motels on Airline Highway, and some on the streets. Laborers gathered in the parking lots of supermarkets and home improvement stores, waiting to be picked up by contractors or home and business owners, and sometimes by unscrupulous people who underpaid or did not pay them at all. If workers confronted them for payment, some contractors threatened to call the police or immigration authorities.

Juan Arroyo, who is Mexican, was one of the so-called “storm chasers”; he came to New Orleans from Orlando, Florida, in September 2005 with three other friends, tools, and a dump truck to work in the reconstruction of homes, mostly in roofing. “There were signs everywhere from homeowners asking for roofers and construction workers,” he said. “There was a horrible smell, like the stench of death, all over the city.” He and his crew ended up renting a room in Slidell, because there were no places to stay in the New Orleans area after the extensive flooding.

He fell from the roof in one of his jobs, broke a foot and an elbow, and sought medical care in one of the clinic tents set up inside of the convention center for emergency situations. “There was a scarcity of medical services,” he explained. He was later sent to Baton Rouge for surgery. After his recovery, Arroyo went back to work, deciding to stay in New Orleans because of labor opportunities. Despite the devastation, there was hope. Taco trucks appeared throughout the city. Spanish radio could be heard everywhere.

Services began to spring up to help the growing community. In December 2005, Luz Molina, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, formed the Workplace Justice Project to defend workers’ rights and provide free legal assistance to low-wage workers. She also helped establish the Wage Claims Clinic in partnership with Catholic Charities and the Pro Bono Project. In 2006, community organizers founded the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice, an organization dedicated to organizing workers across racial and industry lines to empower them in the post-Katrina landscape and ensure their dignity and rights. The Congreso de Jornaleros (Congress of Day Laborers) is one of its branches, aiding workers who look for jobs at sites like Lowe’s and Home Depot. Workers meet weekly and learn how to defend their rights. The Congreso is involved in campaigns for justice, speaking on behalf of immigrants targeted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and facing risks such as deportation. Congreso members are involved in education projects, including street theatre, to educate others about their rights, and radionovelas, recording the stories of undocumented workers in the United States. Honduran laborer Santos Alvarado was one of the senior organizers and represented Congreso on August 20, 2015, when the New Orleans City Council honored the organization for the workers’ role in our city’s reconstruction after Hurricane Katrina.

In the aftermath of Katrina, Latino/as moved to New Orleans in record numbers to work in rebuilding the city. Men and women, documented and undocumented, came from Mexico, Central America, and Brazil, as well as from other cities in the United States.

Before Katrina, the Hispanic Apostolate, a division of the Archdiocese of New Orleans, addressed the needs of the Latino/a population. Nicaraguan-born Martin Gutierrez served as Executive Director of a staff of five, providing emergency assistance, immigration services, help finding jobs, health care, counseling, and educational programs. “When Katrina struck, the city looked like a war zone,” said Gutierrez, who returned two weeks after the storm to examine the needs of Latino/as living in the area. “The workers were living in abandoned warehouses and had all kinds of problems and health issues.” He said there were limited resources available for previous residents of the city, but the situation was worse for those who had come from other places to work in the reconstruction.

In the two years following the storm, the Hispanic Apostolate, working with Catholic Charities, had to increase its staff to fifty people, assisting not only the pre-Katrina population that had returned to New Orleans but also the newcomers who had been working in rebuilding the city. Gutierrez, in addition to his job as Executive Director of the Apostolate, took on the role of Director of Immigration and Refugee Services at Catholic Charities from 2005 to 2008. “With the unexpected growth of the Latino/a community, there was a space that needed to be filled that the existing organizations could not handle,” emphasized Gutierrez. In 2007, he and Hispanic Apostolate volunteers Salvador Longoria and Berta Montenegro envisioned a new entity called Puentes New Orleans to look after the needs of the growing Latino/a community. Puentes means “bridges” in Spanish; the organization’s mission is to build bridges connecting Latin American immigrants and their children to the greater New Orleans community.

Since 2008, Puentes has worked to promote social change through policy research, advocacy, and civic engagement in the areas of education, health, housing, and economic asset building, providing Latin American families in our area with resources to thrive. “It is a secular agency to empower Latinos and to integrate them fully into the mainstream,” said Longoria, a Cuban-born attorney, who serves as Executive Director. A graduate of Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, he has extensive experience working with indigent people and immigration detainees in Louisiana, representing them at court hearings. “Puentes has successfully bridged the gap for many Latinos,” emphasized Longoria. He added that the educational component, known as Escalera (“ladder”), and the Youth Action Council are currently the main focus of the organization.

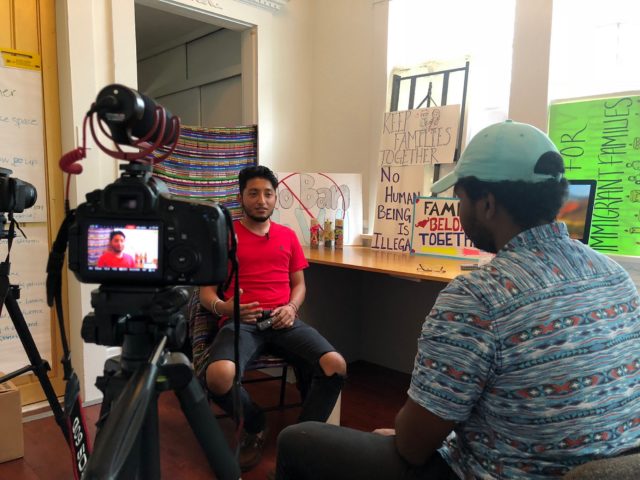

Bryan Gonzales, a University of New Orleans student from Mexico, shares his testimonio with Fredy Tejada during a Puentes Filmmaking and Storytelling workshop. Photo by Jenn Miller Scarnato

As a resident of Mid-City, Longoria noticed other positive developments with regard to Latino/a resources in New Orleans. Along the Mid-City corridor, Latin American restaurants like El Rinconcito and Taqueria Guerrero opened to feed the large number of Latino/as living in the area. Maria Luisa Barrera, native of Guatemala and owner of El Rinconcito, designed the restaurant with a bar and snack tables in the front “so the workers could stop by, have drinks and authentic food like at home,” said Barrera’s son, Mervin Duque, who manages the restaurant. They have added a large family dining area in the back. The same year, Methodist Reverend Oscar Ramos-Gallardo and his wife Reverend Juanita Ramos, who had come to New Orleans from Indiana to minister to the needs of the Latino/a community following the storm, founded La Semilla (The Seed) at United Methodist Church, a non-profit Hispanic-Latino/a center for educational development, offering English classes, helping families navigate the US educational system, and providing other assistance for immigrants.

Other additions to local resources serving the Hispanic community followed. New Orleans Children’s Health Project at Tulane University partnered with the Apostolate to establish mobile health clinics staffed with bilingual professionals at school and church sites. With the arrival of many Mexicans, the Consulate of Mexico in New Orleans, which had closed in 2002 due to budget cuts by the Mexican government, reopened in 2008. The Hispanic Forum surged as a network of groups serving the Hispanic community that saw the need for increased communication and collaboration. Currently coordinated by Daesy Behrhorst and Karla Sikaffy duPlantier, the Hispanic Forum has evolved into an information clearinghouse for local Latino/a organizations. And in order to respond to language access needs identified after Hurricane Katrina, the Louisiana Language Access Coalition was created to eliminate language barriers and promote full and meaningful participation in public life for all people.

As workers brought their families to settle in New Orleans, many public schools saw an increase in Spanish-speaking children needing English as a Second Language programs. Esperanza Charter School emerged as the school of choice for the majority of Spanish-speaking children living in the Mid-City neighborhood. The New Orleans Hispanic Heritage Foundation, founded in 1989, increased the number of scholarships available for Latino/a students, including college scholarships for deserving students in the public schools; in 2018, sixty-three Latino/a students from eighteen public, private, and parochial high schools in the New Orleans area received scholarships.

Despite the devastation, there was hope. Taco trucks appeared throughout the city. Spanish radio could be heard everywhere.

The city gradually returned to normalcy, though with a new outlook on education and business. Revitalization is evident in the boom of startup businesses. According to the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce in Louisiana (HCCL), Latino/a-owned businesses nationwide grew 47 percent—compared to the non-Latino/a increase of 14.5 percent—in the decade after Katrina and are generating billions in revenue. “Many of the reconstruction workers became entrepreneurs,” said Mayra Pineda, President and CEO of HCCL.

Arroyo, for one, saw his business prosper. “From cleaning up mold and lead and putting up roofs in 2005, I have now a well-established construction company with a very good clientele, and I am happy to be in a multicultural city with fair working practices,” he affirmed, although he notes that some people never paid him for his work during the post-Katrina reconstruction. After these successes, the HCCL shifted its focus from providing services for businesses to reaching out to the underserved; they have opened the Bilingual Workforce Training and Business Development Center in Kenner, offering classes in English, citizenship, business, and technology. In addition, HCCL organizes women’s symposia and town hall–style round tables, and its young business members have created the Hispanic Young Professionals of Louisiana group. Because of its growth, the United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce presented HCCL with the Chamber of the Year Award for 2017.

Programs continue to emerge to serve the Latino/a community in New Orleans. In 2010, the New Orleans Police Department started a program titled “El Protector” in recognition of the numbers of Hispanic workers who were vulnerable to assault and theft, since they were paid in cash, and often suffered employer abuse, but could not report crimes because of a lack of Spanish speakers on police staff. El Protector aimed to protect Latino/a residents and empower them to report crimes and abuses by helping them trust local police. Officer Janssen Valencia was assigned to act as liaison with the Spanish-speaking population; he also taught basic Spanish to some of his fellow officers so they could respond better to Latino/as’ needs. In 2014, Mary Moran and Henry Jones co-founded Our Voice/Nuestra Voz, which helps parents of Hispanic children in Orleans Parish public schools access the education system and serve as advocates for their children. In Kenner, the Hispanic Resource Center, established in 2003, has increased its free services such as legal clinics and health fairs. The latest challenge is to protect the rights of new immigrants to New Orleans, including unaccompanied children who have fled rampant violence in their native countries. Local lawyers and the groups Immigration Services and Legal Advocacy (ISLA) and Project Ishmael are committed to working pro bono with these children and immigrants detained in centers in Louisiana.

Cultural events and entertainment related to the Latino/a community have also flourished, with more Spanish radio stations and newspapers, as well as Hispanic festivals like the Que Pasa Fest appearing on the local scene. One week before Katrina struck, the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra hired Mexican conductor Carlos Miguel Prieto as its musical director. After the storm, he advocated for the cultural renewal of the city, conducting concerts in other venues, while the LPO’s usual venue, the Orpheum Theater downtown, lay damaged. In March 2006, world-renowned Spanish singer Plácido Domingo sang at a benefit concert for the New Orleans Opera.

Latino/as are producing art with social import as well; Ecuadorian-born artist José Torres-Tama has provided a strong voice for immigrants through his ALIENS Taco Truck Theater Project, exploring the myth of the American dream and the Latino/a immigrant experience and portraying it in bilingual poems and theatre performances. His goal is to honor the Latino/a immigrant workers who helped rebuild New Orleans after Katrina and to bring attention to the variety of Latino/a creative artists who have contributed to the city’s post-storm arts renaissance.

Challenges remain. One of the most significant is to engage Latino/a residents in the civic and political life of the city in order to secure better representation among elected officials. New Orleans is fortunate to have Veracruz, Mexico-born Helena Moreno, Vice President of the New Orleans City Council and First Division Councilmember-at-Large. An award-winning investigative reporter for NBC affiliate WDSU-TV who covered the devastation after Katrina, Moreno developed a strong voice as a Louisiana legislator before being elected to the New Orleans City Council. “A big debt and recognition is due to the Latino/a workers who worked so hard in the reconstruction of New Orleans,” said Moreno at the dedication of a Crescent Park monument erected in November 2018 in their honor; their sacrifices made it possible for all of us to return to our homes and build a better future for our city and our children.

A path to a bright future is in the making. The latest studies predict the US Latino/a population will reach thirty percent of the total population by 2050, making the United States the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. Latino/as already constitute the nation’s largest ethnic group, and according to researchers with the Peterson Institute for International Economics, they are and “will continue to be a huge economic driver for decades,” due mainly to the great increase in the number of Latino/as in the US workforce and the quality of their participation. Though progress continues to be made, challenges remain ahead for New Orleans’ Latino/a community. As HCCL’s Pineda said, “The Hispanic community is powerful and noble. However, we still need to continue to find our voices, our passion, and purpose to reach our goals with excellence and be recognized as important contributors to the economic development of the State of Louisiana.”

Ana Ester Gershanik, the writer of the “Nuestro Pueblo” weekly column for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, was born in Rosario, Argentina. She is a Fellow of the Institute of Politics at Loyola University and has been the recipient of numerous awards. She is a member and past officer of many civic and charitable organizations at city, state and national levels.