Summer 2021

Plantation Gothic

The first published short story by an African American author and its Louisiana roots

Published: May 28, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

David A. Barnes / Alamy Stock Photo

Odéon Théâtre de L’Europe, Paris.

“Le Mulâtre” takes place on the French colony of Saint-Domingue sometime before the island’s rebirth as Haiti in 1804. By adopting a historical setting, Séjour invites readers of his tale to examine the legacies of slavery and colonialism that link Saint-Domingue with other former French colonies, including Séjour’s home state of Louisiana.

Throughout the story, Séjour takes particular aim at the Code Noir, the French colonial laws that defined conditions of race, slavery, and freedom. Depending on the time period, different “Black Codes” applied to Saint-Domingue and Louisiana, but all versions shored up a white social world structured by the exclusion of Black and Indigenous peoples. In “Le Mulâtre,” Séjour demonstrates how the lingering effects of the 1724 Code—particularly its restrictions concerning interracial relationships and the inheritance of property—erode kinship ties within families than span colonial racial categories. At key moments, however, he also invokes Vodou—another shared cultural feature of Saint-Domingue and Louisiana—to call attention to social networks and sources of power that exist outside the colonial order.

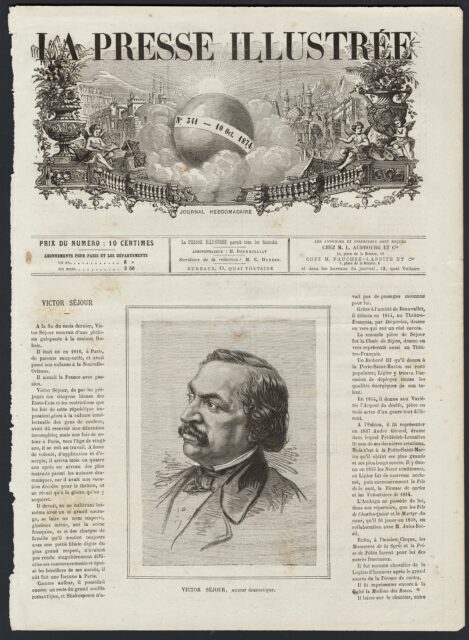

October 10, 1874, edition of the Paris newspaper La Presse Illustrée, featuring Séjour’s portrait and obituary. The Historic New Orleans Collection

From New Orleans to Paris

Séjour was born in New Orleans—a city shaped, like Saint-Domingue, by the collision of French colonial and African diasporic cultures. His mother Eloise Ferrand was a free woman of color descended from a New Orleans Creole family, while his father Louis Victor Séjour was a free Black man who immigrated to New Orleans from Haiti and ran a series of successful businesses, including a dry goods store on the corner of St. Philip and Bourbon Streets. As a budding writer, the young Séjour studied alongside other free Black children at the Académie Sainte-Barbe, which was located just blocks from where enslaved people gathered to socialize and trade goods in Congo Square. At the Académie, Séjour read and wrote under the direction of journalist Michel Séligny, and he attended Creole literary salons, including those hosted by the Société des Artisans, an organization of free men of color to which his father also belonged.

Séjour’s education and affluence, however, could not protect him from the increasingly oppressive restrictions that Black New Orleanians faced during the early nineteenth century. New laws influenced by the Code Noir (which, though technically expired, continued to shape state policies) tightened restrictions around interracial contact and free Black people’s access to public spaces. Meanwhile, an 1830 law that banned the circulation of so-called incendiary writing narrowed avenues for public protest.

Perhaps in response to this attack against the free press, a teenaged Séjour left New Orleans for Paris, where he remained until his death in 1874. In Paris, Séjour befriended other writers of African descent, including Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers. He also began writing for the theater, becoming—as the Times-Picayune reported on May 10, 1874—“one of our prominent dramatists,” whose plays appeared on stages throughout Europe and the United States. By the time of his death from tuberculosis, Séjour had authored over twenty plays as well as poems (including a piece in the 1845 Creole anthology Les Cenelles), part of a serialized novel, and “Le Mulâtre.”

“Le Mulâtre” is the only text in which Séjour deals explicitly with slavery. Most of his extant works take up historical themes or contemporary European affairs, which may reflect his attempts to evade the censorship of the French public. Yet throughout his writing, Séjour returns again and again to the power struggles that attend the transfer of family names and wealth. While his plays leave America behind, his persistent interest in questions of identity and inheritance suggests that Séjour did not turn away from the social problems he introduces in “Le Mulâtre.” Newspapers report that near the end of his life Séjour had begun work on a play titled “L’Esclave” (“The Slave”) and planned to write another about the life of abolitionist John Brown. Though archival manuscripts have yet to surface, the trace evidence of these plays hints at a more explicitly political orientation that Séjour may have returned to late in his career.

A Father’s Denial

Like many of the dramas Séjour would go on to write, the plot of “Le Mulâtre” advances through repeated family tragedy. Following a brief frame narrative, which introduces an elderly Black man named Antoine as the story’s narrator, the tale begins with the sale of Laïsa, Georges’s mother, to Alfred, a wealthy young colonial landowner. After Laïsa is forced to bear Alfred’s child, we are told that Alfred “refuse[s] to recognize” Georges; soon thereafter the enslaver banishes mother and son to the far corner of his plantation. When Laïsa dies, Georges finds himself growing closer to Alfred, though he remains unaware of his enslaver’s true identity. His loyalty is shaken when Alfred assaults Georges’s wife, Zélie, who resists, wounds Alfred, and—by order of the Code Noir—is sentenced to death for her attempt on her enslaver’s life. Distraught, George flees to a community of maroons, people who have self-liberated from slavery, but returns to seek revenge for Zélie’s murder once Alfred marries and has another child. In the story’s climactic final scene, Georges beheads Alfred—who at the very same moment admits he is Georges’s father.

The 1830 incendiary literature law prevented Séjour from publicly circulating his text in Louisiana, though in Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition scholar Caryn Cossé Bell suggests that Séjour’s family members may have shared copies in private. Any Louisianans who did get hold of the story would likely have recognized the specter of the 1724 Code Noir in the tale’s defining act: Alfred’s refusal to recognize Georges as his son.

Like other Black Codes, the 1724 Code Noir sought to regulate intimate relations between white and Black people, in part because colonial leaders feared the shift of power that might occur if children of interracial unions could inherit from white parents. Among its restrictions, the Code banned marriage between Black and white subjects, as well as inheritance across the color line. This did not stop some white enslaver fathers from finding ways to grant their Black children property, but in “Le Mulâtre,” Alfred refuses to entertain this possibility.

Instead, by denying that Georges is his son, Alfred holds on to his wealth in more ways than one. Georges is both potential inheritor of family property and, as an enslaved person, inheritable property himself. According to Article 40 of the 1724 Code, slaves were “meubles”—a French word meaning “movables” or portable goods. In the frame narrative that begins “Le Mulâtre,” Séjour underscores the dehumanizing nature of this statute through Antoine, the narrator of Georges’s story, who describes slavery as a condition under which “free men . . . become, through violence, the goods, the property of their fellow creatures.” Highlighting the violence of treating people as property, Antoine’s words encourage readers to see Alfred’s refusal to recognize his son for the violent act it is.

Portrait miniature of William C. C. Claiborne, ca. 1805. Painting by Ambrose Duval, The Historic New Orleans Collection

A Child’s Inheritance

Séjour exposes the desire for wealth that motivates Alfred to disavow his enslaved child through the image of a small portrait—an object described as Georges’s “sole inheritance.” Laïsa gives her son a bag containing this portrait shortly before her death. Although she tells Georges that the portrait depicts his father, she makes him promise not to open the bag and learn his father’s identity until he turns twenty-five, fearing for Georges’s safety if he learns the truth before he is grown and “able to keep such a secret.”

Small portraits like the one Georges carries were common nineteenth-century accessories, particularly among the wealthy. Sometimes described as “portrait miniatures,” these images range in size from a few centimeters to a few inches tall. Users typically exchanged portrait miniatures to assert social status and strengthen close relationships. Such objects often helped users cement family belonging; in at least one nineteenth-century court case, a judge admitted a miniature as proof of identity in a major family inheritance lawsuit.

Séjour does not reveal how Laïsa comes to acquire Alfred’s portrait. But portrait miniatures’ association with wealth and intimate family attachment make the object an ironic one for Georges to carry. If the hidden portrait is, as Séjour writes, Georges’s “sole inheritance,” it’s because Georges stands to inherit little else from his father. Unseen by Georges, the portrait calls to mind the very relationship and potential inheritance that Alfred keeps from his son.

The portrait’s status as Georges’s “inheritance” also suggests that Laïsa’s reluctance to let Georges view his father’s image before he comes of age may reflect an attempt to counter the violence of Alfred’s greed. As Laïsa tells her son, “he [Alfred] forbade me to talk to you of him, under the threat of his hating you, and, you see, Georges . . . the hatred of that man is death.” Proof of a bond both Alfred and colonial society wish to repress, the portrait is a dangerous object.

A Mother’s Gift

Although the concealed portrait in “Le Mulâtre” is evidence of one family relationship severed under the Code, the leather bag containing the object attests to another family member’s enduring affection. The “little buckskin bag” that Laïsa gifts her son along with the portrait evokes amulets used throughout Africa and its diaspora. These amulets, which are known by names including gris-gris and conjure bags, vary in function but commonly offer wearers forms of personal protection. Viewing the bagged portrait as a gris-gris opens room within “Le Mulâtre” to reconsider Laïsa as a character who wields more agency than might seem apparent at first glance—and whose care for her son is felt even beyond the grave.

In the early Americas, gris-gris functioned as protective objects but over time came to spell resistance, often in connection with Vodou practice. During the late eighteenth century, several enslaved men in New Orleans were put on trial for allegedly conspiring to use gris-gris to kill their enslaver. City authorities responded to the incident by revising the Code to prohibit certain African rites and burial practices.

Like portrait miniatures, gris-gris could link users to broader communities; unlike miniatures, they operated outside the colonial regime. In “Le Mulâtre,” the buckskin bag is one of multiple moments of revolution and resistance in which Georges encounters sources of authority outside his father’s control. Most obvious is the group of maroons, to whom Georges escapes following his wife Zélie’s death, who greet each other with the phrase “Africa and liberty” and end the story lying in wait, their presence hinting at the coming Haitian Revolution. But there is also the scene in which Georges arrives to seek his revenge on Alfred. As Séjour writes, Georges rises up before Alfred as “a sort of motionless shadow, its arms crossed on its breast, and two burning eyes” and speaks to his father with “a voice that seemed to rise from the tomb.”

This deliberately ambiguous passage suggests a moment of spirit possession—worked, perhaps, through the power of Laïsa’s gris-gris. “Given over to his terrible role,” Georges seeks revenge against his enslaver’s crimes, bringing down the ax as Alfred speaks: “Strike, executioner . . . strike . . . you may as well kill your fa—” (the ax strikes, the head rolls) “—ther.”

In a Gothic twist, Alfred’s head appears to speak even after it falls to the ground. The moment registers the otherworldly horrors of the slave plantation and a issues reminder that seemingly immutable systems—slavery, colonialism, the authority of fathers—are possible to reimagine, to overturn.

Audiences and Afterlives

Modern audiences thought little about “Le Mulâtre” until 1997, when Philip Barnard’s English translation of the tale appeared in the inaugural edition of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature. But Séjour’s earliest readers spanned the globe. The Revue des colonies, the journal in which the story first appeared, circulated in France, Haiti, French Senegal, the French Indian Ocean colony Île Bourbon (now Réunion), French and British Mauritius, and seven Caribbean colonies. Audiences read “Le Mulâtre” alongside poems, anti-slavery letters, and articles about current events, all commissioned and edited by Cyrille Bissette, a free man of color from Martinique.

In 1836, Bissette had been accused during a political trial on Île Bourbon of using his publication to incite revolution. Although Bissette denied the charge, the March 1837 issue of the Revue contained reporting critical of the Bourbon trial as well as the debut of Séjour’s “Le Mulâtre.” Bissette’s choice to publish Séjour’s tale suggests a desire to promote its revolutionary spirit and willingness to call colonial abuses to account, even as Bissette was careful not to call for revolution outright in the Revue’s pages. Sometimes fiction, with its ability to sustain ambiguity, is the right tool for change; and in “Le Mulâtre,” Séjour shows just how powerfully the imagination can unsettle.

Madeline Zehnder is completing her PhD in nineteenth-century American literature at the University of Virginia.