Refugee Revolution

Covering the crisis that more than doubled New Orleans’s population

Published: May 29, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

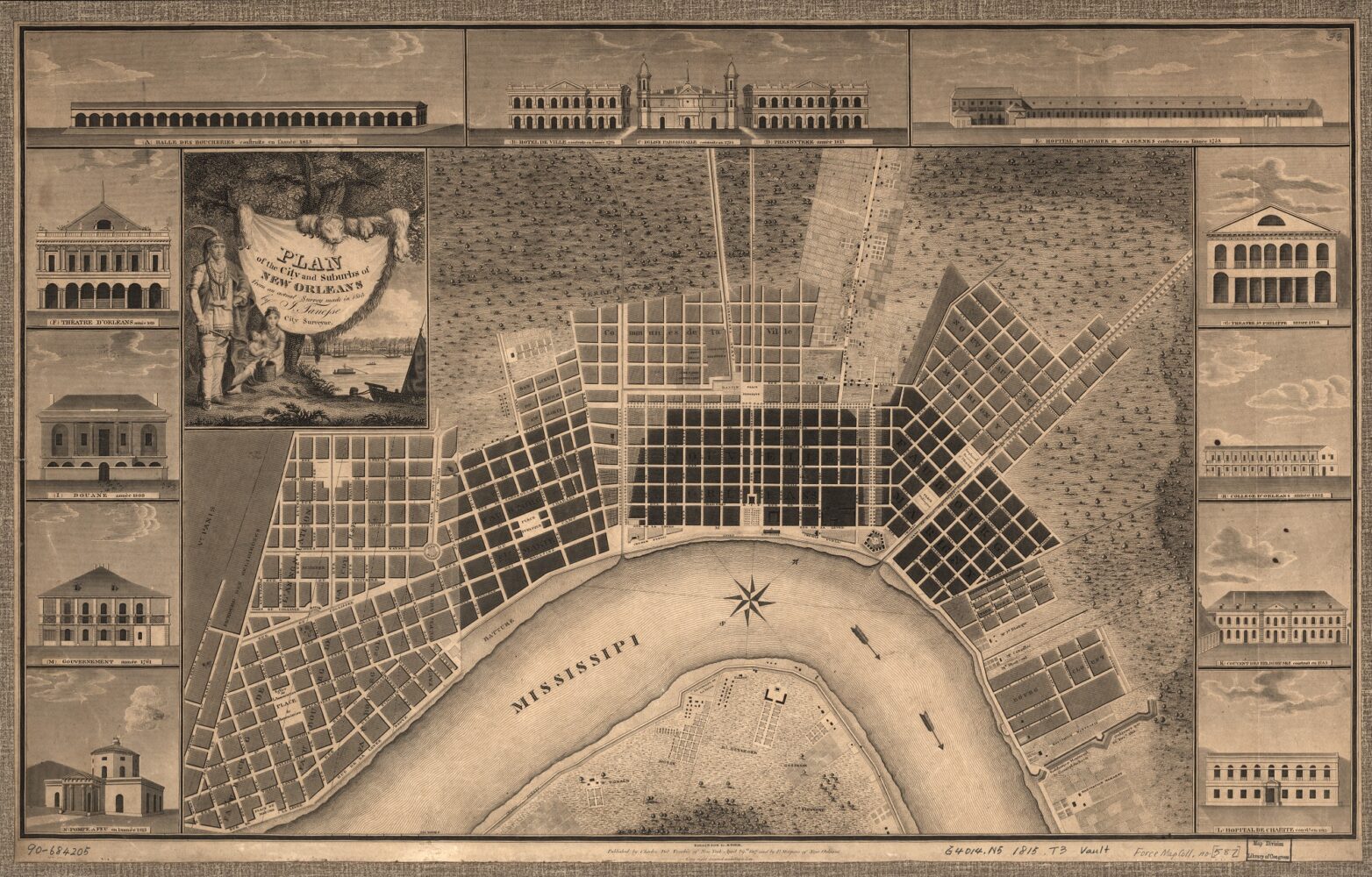

Library of Congress

Detail from the 1815 Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans by I. Tanesse showing two neighborhoods where many refugees settled: Faubourgs Marigny and Tremé.

A city of roughly eight thousand residents in 1805, New Orleans immediately felt the demographic impact of the refugees’ arrival. The city had seen previous waves of Saint-Domingue refugees in the 1790s and again in 1803–1804, but their numbers were slight compared to the influx from Cuba, which doubled the city’s total population in nine months. Mayor James Mather provided his official tally of the refugees in January 1810, which included a breakdown by race and status. The number of individuals in each group—white people, free people of African descent, and enslaved people of African descent—was almost evenly divided into thirds. Although their numbers were roughly equal, the initial reception of each group was decidedly not. A look at the way newspapers covered the Saint-Domingue refugee crisis in New Orleans reveals how the political perception around their arrival was conditioned by the refugees’ race, status, and gender.

The Saint-Domingue émigrés landed in New Orleans during the territorial period (1803–1812), a transitional time for Louisiana. Governor William C. C. Claiborne strived to maintain control over a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, and multi-lingual population navigating the new terrain of American rule. More than half of New Orleans’s residents were French-speaking people of African descent, two-thirds of whom were enslaved. The free population included recently arrived Anglo-Americans who vied with white Creoles for political power and free people of color who sought to maintain their rights under the new government. The refugees from Cuba introduced into this fractious population another affinity group (Saint-Dominguans) that at once augmented three French-speaking social groups in New Orleans. Their presence also raised the specter of the Haitian Revolution, a bloody war that began with a major slave uprising in 1791 and ended with the creation of the independent nation of Haiti, following the defeat of the French by people of African descent.

The arrival of the Saint-Domingue refugees elicited a divided public response among white residents of New Orleans. These divisions mainly fell along ethnic/language lines. Governor Claiborne explained in a letter that “[t]he foreign Frenchmen residing among us take great interest in favour of their Countrymen, and the sympathies of the Creoles of the Country (the descendants of the French) seem also to be much excited.” English speakers, however, “appear to be prejudiced against these Strangers, and express great dissatisfaction that an Asylum in this Territory was afforded them.” While exceptions could be found within both groups, articles in newspapers in New Orleans and other US cities support Claiborne’s general depiction.

The white-controlled press promoted these differing viewpoints through editorials, letters, and notices for and about the refugees. By 1809, New Orleans had several newspapers, including the French-language Moniteur and Courrier de la Louisiane as well as the English-language Louisiana Gazette and Orleans Gazette. While all four of these newspapers printed information about the refugees’ arrival, the French-language papers dedicated far more coverage to the influx from Cuba. The Courrier presented white refugees as hardworking planters who were destitute through no fault of their own. Editorials in the English-language papers often offered sympathy for white refugees, but they lamented the fact that an influx of Francophone émigrés bolstered New Orleans’s white Creole population to the detriment of Anglo-Americans moving to Louisiana from other states.

Papers also printed negative depictions of the refugees. In a letter to the editor of New York’s Freeman’s Journal (reprinted in a Virginia paper), a New Orleanian portrayed the refugees as a “motley collection” of white pirates with “mulatto mistresses,” “blood-thirsty miscreants” of color, and “negroes . . . such as you generally find in the West Indies.” While white newspapers expressed differing opinions about white refugees according to the language of their readership, they aligned more closely in regards to the racial status of refugees and looming stresses on city resources.

The arrival of the Saint-Domingue refugees presented New Orleans authorities with an immediate humanitarian crisis. Many people arriving from Cuba had few resources with which to support themselves. The refugees’ relocation to Louisiana was at the very least the second time they had been displaced from their homes; for many, this move was just one of a series they had made since the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution. Those who had acquired Cuban real estate were forced to sell it before sailing to New Orleans. The refugees needed food, housing, and a way to earn a living. Although Claiborne had faith that New Orleanians would provide “the most friendly hospitality” to the refugees seeking “asylum” in Louisiana, he worried “that so great and sudden an Emigration to this Territory, will be a source of serious inconvenience and embarrassment to our own Citizens.”

Whether the viewpoint was pro- or anti-refugee, most articles expressed concern not for the people trapped on small ships docked along the banks of the Mississippi River but for their white enslavers.

New Orleans authorities took immediate steps to manage the refugee situation. On May 17, the mayor requested that the city council create a committee to raise money and find work for the refugees. Following city council approval, notices about the newly formed Welfare Committee appeared in the English- and French-language papers. The committee selected a list of citizens, almost all French speakers, who were responsible for collecting financial donations and other offers of assistance from residents. By August, more than five thousand dollars had been raised and distributed, with another round of fundraising announced. The Moniteur also printed opportunities for employment and offers of land leases for refugees. Not long after the first Welfare Committee notification was published, a previously organized Welfare Society announced a collection “in the name of suffering humanity, to renew their efforts to provide the means to come to the aid of these unfortunate people.”

The Moniteur printed recurring notices about these charity organizations, but none of the articles refer to the race or status of the intended recipients. A statement published on May 24, however, makes clear that refugees of African descent were not included in these first two collections. On June 24, the Moniteur published an announcement from Mayor Mather that asked free people of color in the city to hold a voluntary fundraiser for the “women of color, recently arrived from Santiago de Cuba, and overburdened with young children.” If they could not organize a collection quickly, charitable free people of color could donate directly to Mather who would make sure the money was used to assist “people of their own class.” By essentially creating segregated welfare committees, Mather indicated that white New Orleanians, whether Creoles or Anglo-Americans, did not feel a responsibility, at least on a public level, to provide assistance to free refugees of African descent arriving in great numbers from Cuba.

The mayor’s offer to distribute money raised by free people of color proved unnecessary. Before the notice was published on June 24, Charlot Brulé and Baptiste Hardy organized a collection to support refugees of color. Within days they had raised enough to rent a house on Bourbon Street to provide temporary “refuge to the unfortunate people of color without means and unable to earn a living.” Brulé and Hardy were prominent members of the city’s free people of color population. Both men were property owners, artisans, and natives of New Orleans. They served together in the free black militia under the Spanish, which linked them to a strong social network from which to raise funds. In answering the mayor’s call for charity, Brulé and Hardy demonstrated that free people of color were not only generous and sympathetic to the refugees’ plight but had the means to raise money and take action.

The gender of free refugees of color tempered white reactions to their arrival. According to the mayor’s official numbers, the vast majority of nonwhite refugees who arrived from Cuba were women and children. Among free people of color, 1,377 women and 1,237 children substantially outnumbered 428 men. These numbers may well reflect the overall pattern of migration among free refugees of color, as more men lost their lives in the war and women and children more easily gained permission to leave the island. Fearing a potential rebellion, the Louisiana legislature further circumscribed the movements of free men of color from Saint-Domingue by banning their entrance into the territory in 1806. Women and children, considered by lawmakers to be innocent victims rather than instigators of the Haitian Revolution, did not face this restriction. The law remained in place in 1809, but Mather admitted to Claiborne that it was difficult to enforce. In an attempt to do so, city authorities required free men of color arriving from Cuba to post a bond guaranteeing their stay was temporary. Very few men actually did this. By August, Claiborne attempted to stop the flow of Saint-Dominguans of color from the source by instructing the American Consul in Cuba “to discourage free people of Colour of every description from emigrating to the Territory of Orleans; We have already a much greater proportion of that population, than comports with the general interest.” Despite these efforts, free refugees of color continued to arrive from Cuba, ultimately tripling the total number of free people of color in New Orleans.

The arrival of more than three thousand enslaved Saint-Dominguans also proved controversial. For reasons similar to those given to justify the ban on free men of color from entering New Orleans, some white residents viewed enslaved people from Saint-Domingue as “dangerous enemies.” Evoking Haiti’s founding fathers, one writer in the Orleans Gazette asked, “Are we to be charged with unfeeling cruelty, for excluding the followers of Toussaint, Dessalines, Christophe, and Pétion from our shores?” Indeed, the possibility that the experiences of refugees of African descent during the revolution would lead to a similar cooperation of enslaved and free people of color against white enslavers in Louisiana made many white people in New Orleans nervous.

A legal issue concerning enslaved Saint-Dominguans added to the controversy and further exacerbated the refugee crisis. The landing of enslaved people from Cuba violated the federal ban on the international slave trade. The 1808 law prohibited the importation of an enslaved person of African descent from any foreign country. Upon learning that the first ship from Cuba carrying refugees had reached Fort Plaquemine, a required stop for vessels entering the mouth of the Mississippi, Claiborne instructed the commanding officer to allow the ship to continue to New Orleans but that the Saint-Dominguans designated as “slaves” on the manifest could not disembark.

White refugees immediately pressured Claiborne to allow their slaves to come ashore. He explained in a letter, “I am assailed every day with entreaties to interfere in [the white refugees’] favour . . . With all my Heart do I sympathise with those poor people; But . . . Congress can alone give them relief, as relates to their slaves.” When appeals to Claiborne did not work, white refugees and their supporters turned to the newspaper. An article in the Courrier argued that allowing refugee slave owners to enter New Orleans without their human property “deprive[d] them of the means of procuring subsistence, and they may become a burthen to the country, to which, if admitted with their slaves, they would be useful.” As for the enslaved people themselves, the Courrier piece described them as “faithful servants who have preferred the horrors of exile and misery to a separation from their masters.”

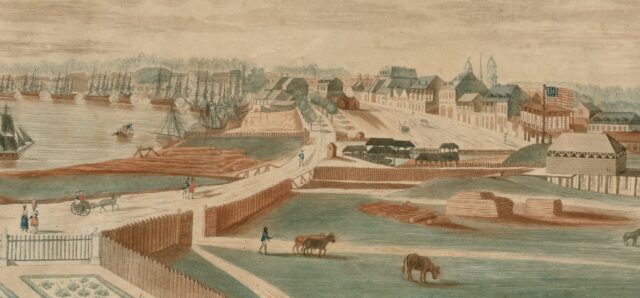

Detail from John L. Boqueta de Woiseri’s 1803 A View of New Orleans, depicting the riverfront looking upriver from the perspective of Bernard de Marigny’s plantation (today’s Faubourg Marigny).

The Historic New Orleans Collection

For white people in New Orleans who opposed the entrance of the Saint-Domingue refugees, the law prohibiting the importation of “foreign slaves” clearly applied in this situation and should be upheld. An editorial in the Orleans Gazette explained this as a matter of public security: “whilst our hearts sympathize with the sufferings of the unfortunate, our own safety may compel us to pursue measures that are not sanctioned by our feelings.” Other editorials portrayed white refugees as cruel slave owners who gambled away the earnings of the rented labor of their slaves.

Whether the viewpoint was pro- or anti-refugee, most articles expressed concern not for the people trapped on small ships docked along the banks of the Mississippi River but for their white enslavers. However, one author in a Philadelphia newspaper used the news of enslaved Saint-Dominguans as an opportunity to make an abolitionist statement. The author, “H.,” lamented “the condition of these unhappy Black People.” H. felt sorry for the refugee slave owners displaced from their homes but reminded readers that circumstances for “the slaves, which at home, and in their best state, are much more miserable than the present condition of the masters.” H. concluded the piece with a call for the end of slavery in the United States.

New Orleans newspapers did not express such sentiments, but by mid-June, it was clear that Claiborne’s detainment solution had become untenable. Having not received a response from Congress, the governor came up with his own plan. He allowed enslaved refugees to disembark and required their owners to post a bond, promising to hand them over to government officials at Congress’s request. Within days of releasing the enslaved refugees, the Moniteur published a letter from five white Saint-Dominguans thanking Claiborne for “allowing them to disembark their negroes on bond.” Meanwhile in Washington, Congress briefly debated and passed a bill that exempted Saint-Domingue refugees from the 1808 foreign slave trade ban. News of the bill’s passage reached New Orleans in late July. The Moniteur published the text of the law alongside a letter to Congress from Edward Livingston in support of the white refugees. With no irony, Livingston wrote: “Forced a second time to abandon the plantations created by their industry, they naturally fixed their hopes on that country which from its earliest existence has been the refuge of the unhappy and an asylum for the victims of oppression.”

The Saint-Domingue refugee crisis in New Orleans is a formative event in our country’s early history that helped establish a national narrative of the United States as a land of welcome. For many Americans, this idea remains one of our nation’s core values. An examination of the politics surrounding the arrival and reception of Saint-Domiguans, however, suggests that not everyone seeking an asylum on US shores finds that welcome offered equally. Although the specific circumstances change, broad patterns illustrated by the example of Saint-Dominguans in New Orleans can be observed in the coverage of more modern refugee crises. Decisions about who deserves assistance and sympathy and who does not continue to be shaped by refugees’ race, gender, and status, while debates over their economic, political, and cultural impact on the host community persist. In the response to a refugee crisis that occurred over two hundred years ago, we see the expression of an American ideal and the obstacles that make it difficult to achieve.

Elizabeth C. Neidenbach earned her PhD in American Studies from the College of William and Mary. She is currently the visitor services trainer at The Historic New Orleans Collection and is revising her manuscript, “The Life and Legacy of Marie Couvent: Social Networks, Property Ownership, and the Making of a Free People of Color Community in New Orleans.”

This article is part of Split Press: Democracy, Race, and Media in Black and White, a four-part multimedia series exploring the relationship between the media and African American and Afro-Creole experiences of citizenship and civil rights in Louisiana. Part of the Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative, Split Press is a project of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities made possible by a grant from the Federation of State Humanities Councils with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For additional Split Press coverage, stay tuned to 89.9 WWNO New Orleans and 89.3 WRKF Baton Rouge.