Poetry by Brad Richard

Racial violence in New Orleans in 1900 and 2005

Published: September 1, 2020

Last Updated: November 30, 2020

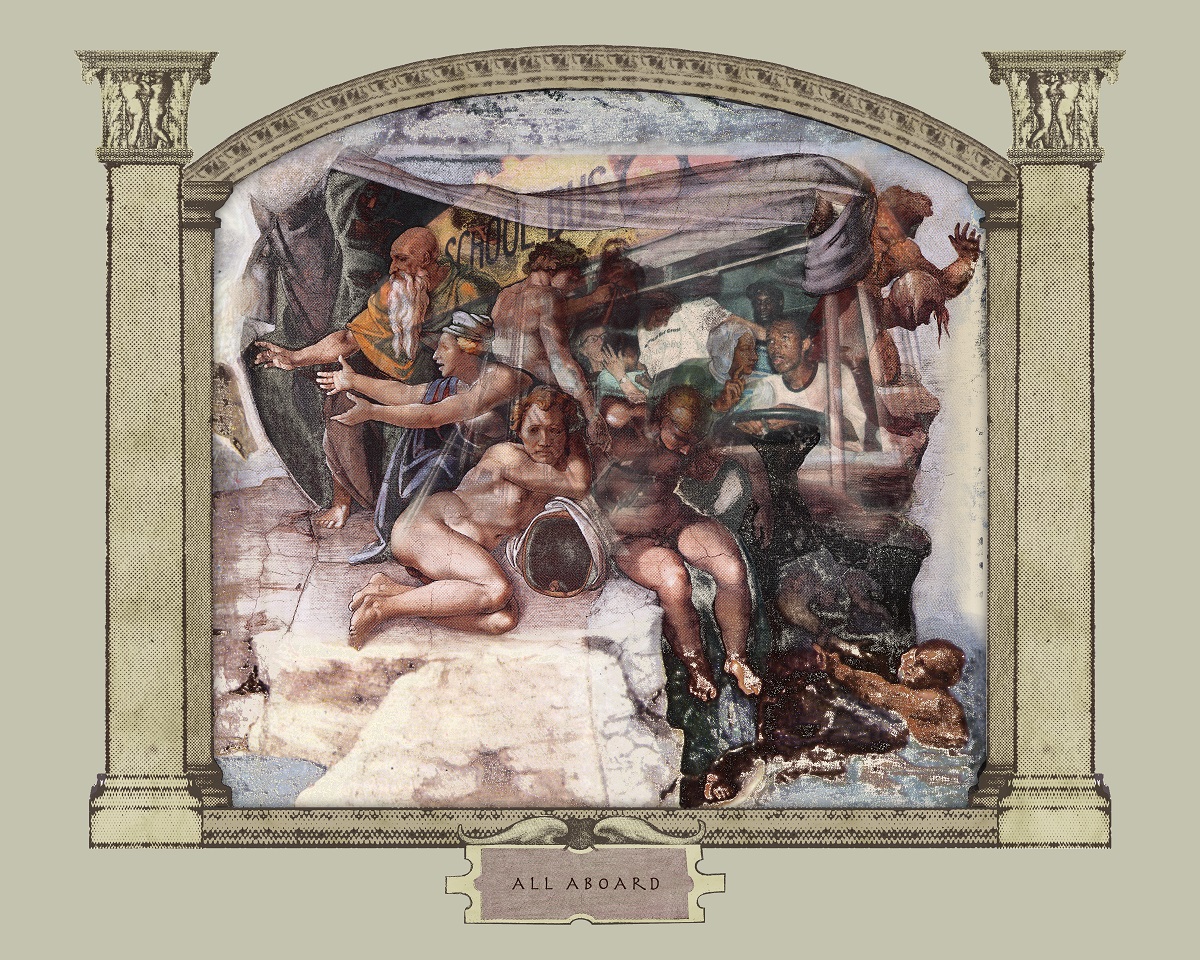

Lou Blackwell

All Aboard, digital collage, 2016.

In the spirit of Jake Adam York, Brad Richard’s poems uncover and bear witness to horrific racial injustices that have been long forgotten. Richard’s voice is a camera, providing gut-stirring details of incidents of racial brutality. His finely crafted poems speak truth that is relevant and truly necessary for contemporary discourse.

—John Warner Smith

The Missing Skull

Where is his skull? a man’s mother asked.

The man was burned in a car. Two men found it

by the river, the corpse shot in the head.

The police did this. After the autopsy, what remained

fit in two vinyl bags.

But how could you lose his skull?

How can I bury my son? She had to bury her son

without his head.

Henry Glover. His skull, wrapped

in newspaper, in a box, in an attic winter and summer

I can’t stop imagining, now

ten winters and summers

among holiday ornaments, old uniforms, trophies.

The plates, the jaw, the teeth, the bullet hole.

Roaches and silverfish have eaten the box.

Wasps have chewed the newspaper

for nests built elsewhere.

And this is as far

as I can go, ant haunting this broken dome.

Landscape with Burning Car

New Orleans, five days after Hurricane Katrina

From the Patterson Drive levee,

all we could have witnessed:

sunset, the sky wrung-out hues.

No seagull’s cry, ferry’s horn, siren.

A calm river. Nothing

in the willows at the water’s edge,

one charred place

where smoke and gasoline

and blistered metal and charred

body and vapored flesh

and a policeman’s spent flare

and his shirt bloody

and a hole in his head

in a white Chevy Malibu

Henry Glover

Night already come down

in the willows at our water’s edge.

For Robert Charles

New Orleans Race Riot, 1900

After you killed the two cops who came for you

and the white mob didn’t know where you’d run,

they got drunk and started hunting down blacks

in gaslit streets, even tried to snatch an old man

from under a white woman’s skirts on the streetcar,

even shot an old fruit seller dead. “Oh,” said the killer,

“he’s an old negro. I’m sorry that I shot him.”

Meantime, in the room you’d fled, while the mayor

passed his evening at the Turkish baths, nosy white folks

poked around for clues. Found the Voice of Missions

bundled near pamphlets preaching “Back to Africa.”

Found pencil-marked textbooks, your name inside.

Found a box of morphine (they said) or cocaine.

Soap scraps, a bullet mold on your mantel—

a thief, a killer. Found, too, in your trunk,

composition books you’d filled, your mind bent—

so claimed a reporter—on learning only

to conquer the white race. Long gone, those notebooks,

with your tailored suits, your Winchester.

The ladies next door thought you a scholar.

“There was an air of elegance about Mr. Charles.”

Ten thousand white men swarmed the boarding house

you’d holed up in, finally smoked you out

when they tired of you picking them off.

Tossed your riddled corpse in a wagon. Your head,

dangling off the edge, bounced hard on the ride

across town to the deadhouse. Jelly Roll

said Storyville had a sorrow song for you,

but “that song never did get very far.”

Brad Richard is the author of four collections of poetry: Habitations, Motion Studies, Butcher’s Sugar, and Parasite Kingdom, winner of the 2018 Tenth Gate Prize from The Word Works. He lives and writes in New Orleans, where he taught talented high school students for twenty-eight years. More at bradrichard.org.