Bookstand

Rethinking Reconstruction

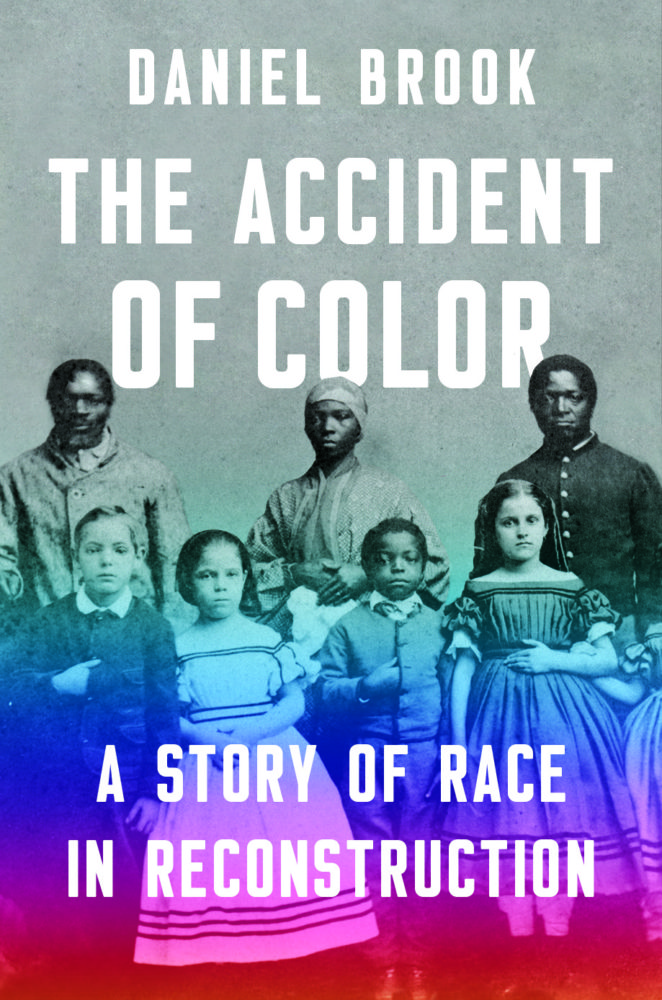

A new history of Reconstruction in Louisiana and South Carolina reveals an alternative path not taken for US race relations

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: August 30, 2019

W. W. Norton

That these two states produced and ratified such progressive governing documents was no accident, according to Daniel Brook in his book, The Accident of Color: A Story of Race in Reconstruction (W. W. Norton, 2019). In addition to having African American majorities (now able to vote per the 1866 Reconstruction Acts), both Louisiana and South Carolina had long-established populations of free people of color in the port cities of New Orleans and Charleston. Predominately of mixed race, the free colored communities in both cities included a significant number of educated property owners with familial connections to white elites. Many of these free black men (and some women) emerged as leaders and activists during Reconstruction, fighting for political and civil rights for all people of African descent.

In The Accident of Color, Brook presents an engaging narrative history of Reconstruction-era events that places mixed-race activists in New Orleans and Charleston at its center. He argues that the development of distinctive communities of free people of color—Francophone Creoles of color in New Orleans and “Browns” in Charleston—produced a generation of leaders who entered the post-Civil War period with the education, financial resources, and networks needed to secure civil rights. They also had experience using the court system and a long tradition of contesting restrictions placed on them because of race. In what should be considered the first civil rights movement, people of African descent fought on the local, state, and national level for the full slate of rights accorded citizens of the United States as well as equal access to public accommodations and transportation and integrated public schools. Although these rights were included in the 1868 Louisiana and South Carolina state constitutions, African Americans had to actively pursue the implementation and continued enforcement of laws that accorded them equality. They did so using tactics familiar to us today as hallmarks of the modern civil rights movement: sit-ins, mass protests, and legal test cases.

Yet, Brook argues that the mixed-race activists at the forefront of these efforts in New Orleans and Charleston envisioned a more radical future than that of activists in the 1950s and 1960s.

In their efforts to gain equal rights for all people, biracial leaders argued not only for the end of racial distinctions in access, treatment, and opportunity, but the end of racial classifications altogether.

Definitions of race were in flux after emancipation dissolved the main social dividing line between free and enslaved in the South. It was during this time that the notion of a “one-drop rule,” which coded all people of African descent as “black,” no matter their skin tone, degree of racial mixture, wealth, or status before the war, became increasingly prevalent. As white supremacists worked to enact a set of race-based rights that made clear distinctions between whites and blacks, the definition of whiteness expanded to include ethnicities and immigrant populations that had not always been viewed as “white” by native-born, Anglo-Americans. Creoles of color and Browns—with their own mixed existence, often having physical appearances that were racially indeterminate, and identities that were neither black nor white—challenged the entire concept of race, exposing its social construction in the process. Ultimately, activists’ successes in gaining rights were short-lived, while their quest to prevent a system of oppression that tied rights to race failed. With the introduction of Jim Crow segregation, racial boundaries between “whites” and “blacks” hardened to such a degree that they remain ingrained in Americans’ view of race today. Brook argues, however, that the legacy of widespread racial mixing makes the notion of separate races absurd because, “as New World people, we [are] too mixed up to sort back out” (296).

The book begins with the development of the substantial populations of free people of color in New Orleans and Charleston during the colonial and antebellum periods and the tripartite racial systems that set the cities apart from the more common black/white binary found in other parts of the United States. The narrative then moves chronologically from the Civil War to the dawn of Jim Crow at the turn of the twentieth century. The heart of the book traces the activism of mixed-race people in New Orleans and Charleston, as they navigated the changing currents of political power by building coalitions with freedmen and white Republicans and continually testing the state and federal governments’ support of their rights through the court system.

Along the way, Brook highlights the stories of a number of individuals like Louisiana’s Robert H. Isabelle and Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez. Isabelle fought for school integration as a constitutional delegate, state representative, and instigator of a test case to integrate the Fisk School in New Orleans’ Third Ward. Roudanez, who received his medical degree in Paris, founded, along with Paul Trevigne, two newspapers that served as the radical mouthpieces of the city’s Civil Rights activists. In South Carolina, leaders like Frances Lewis Cardozo, an educator with Jewish, African American, and Native American ancestry, chaired the Committee of Education for the constitutional convention, and eventually served as state treasurer. Cardozo was joined on the Education Committee by Henry Y. Hayne, a tailor from Charleston whose white uncle was an antebellum governor. Hayne served as state representative, land commissioner, and eventually secretary of state. He was also the first student of color to attend the University of South Carolina. Recognizing the achievements of these men and others whose civil rights activism has been obscured, Brook suggests, offers inspiration to think outside of the racial box.

In 1903, the street cars in New Orleans, which had been integrated since 1867, acquired moveable screens for segregated seating. That same year, W.E.B. DuBois declared, “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” As Brook demonstrates, Reconstruction-era mixed-race activists like Roudanez in New Orleans and Cardozo in Charleston offered a solution to this problem—albeit one so radical it is difficult to imagine today.

Elizabeth C. Neidenbach earned her MA and PhD in American Studies from the College of William and Mary. She has worked as a public historian for the National Park Service in Virginia and New Orleans and currently works for The Historic New Orleans Collection.