Magazine

Scorchers, Wheelmen, and Flyers

The brief but significant life of Audubon Driving Park.

Published: June 1, 2016

Last Updated: April 30, 2019

Cycling races had taken place in New Orleans for only a few years before beginning to rival boxing and baseball as spectator events. Contests of the city’s “wheelmen” got their start as popular entertainment in New Orleans in 1887, when the cycling races were first held at the short-lived and long-forgotten Audubon Driving Park—inside what is now Audubon Park. The Exposition Track, as it was originally called, was the site of not only the first bicycle track races in New Orleans but also the first strictly professional baseball games played in the city. Not a trace of the venue remains, but the Audubon Driving Park is where New Orleans took its first steps into the modern era of national-level interurban sports rivalry.

Sports at the American Exposition

The Exposition Track was built in 1885 as part of the North Central and South American Exposition. This was the dawn of the golden age of industrial expositions, or “world’s fairs,” that lasted into the early 20th century. As the United States rapidly urbanized, a spirit of “city pride” took hold, prompting municipal leaders to promote their cities in vigorous competition. Ambitious industrial fairs that displayed cultural marvels, scientific wonders and technological innovations from around the world alongside local cultural assets were held to show off a city’s success and modernity. New Orleans held its World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition from December 1884 to June 1885. Later that year, a new enterprise, known commonly as the American Exposition, was conceived as a remedy to the financial failure of the World’s Exposition.

Louisiana Cycling Club members gather outside their clubhouse, located at 1637 Octavia Street. Founded by railroad clerk Richie Betts, the LCC attracted younger members of the city’s middle class. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

The objective of the new American Exposition was to attract larger and more profitable crowds with a new vision for the industrial fair. As part of their plan, management proposed adding a baseball diamond. Although baseball had been around for a few decades, in the 1880s its popularity was booming as national rules were established and new railroad lines made the teams’ movements faster and cheaper, allowing for exciting contests between professional teams representing their cities.

In early October 1885, a month before the American Exposition’s November 10 opening, plans were announced to construct a diamond and grand stand for Exposition Ball Park in the area between the Main Building and the river. William F. Tracey, a representative of the American Exposition, was reported to be in Chicago negotiating to bring at least one professional “nine.” New Orleans had a number of amateur teams and semi-professional touring teams but lacked a professional nine to represent the city. The Exposition management faced a dilemma: either bring two professional teams to New Orleans at great expense or try to get together a formidable enough professional nine to represent New Orleans against the visitors.

As the plans for the baseball park were under discussion, a horseracing track was in the works on the northeast corner of the grounds, next to St. Charles Avenue. Exposition Race Track would be the first horse racing grounds at an industrial exposition. Organizers converted the central barn from the World’s Exposition’s agricultural exhibits into a grandstand, rolled a quarter-mile track and built stalls for 200 horses. The grandstand was an elaborate structure designed to seat 4,000 and included retiring and reception rooms for ladies, as well as a restaurant. Only a week after initial plans for the baseball park were laid out, the management decided to put the baseball diamond inside the racetrack, which gave the venue a dual purpose and spared the expense of constructing two grandstands. With the money saved, they could afford to bring two professional baseball teams to the city.

Cycling in New Orleans gained rapidly in popularity, especially with the young men of the Uptown bourgeoisie, as bicycles became more affordable.

A week after the official opening of the American Exposition, on November 16, 1885, the St. Louis Browns and the New York Giants played the first game at Exposition Ball Park—the first time two professional baseball teams had faced off in the Crescent City. This first series of games, held over several weeks, was a huge success. As the Daily Picayune wrote December 5, “The Exposition has created a more genuine and healthy interest in baseball and athletic sports generally than ever before existed in this community. Baseball, especially, has received a genuine boom, and business men have become as enthusiastic over it as the most steady patron.”

Afterwards, New Orleans’ appetite for professional baseball continued unabated, and fans clamored for a professional team of their own. For the 1887 season, New Orleans was awarded a city franchise team, nicknamed the Pelicans, in the all-professional Southern League. New Orleans caught “baseball fever,” and the Pelicans took the championship title in their first season.

The first horse racing season at the Exhibition Track, which promised “the grandest racing ever seen in the South,” opened with fanfare December 8. The new racing grounds attracted large crowds, and its stables brought in, according to the Picayune, “the finest collection of thoroughbreds ever known to New Orleans.” After the closing of the American Exposition in 1886, the racing facilities were sold but continued to operate as before.

By 1887, the Audubon Park Commission was trying to raise money to maintain and improve the old exhibition grounds, which had been renamed Audubon Park, for public use. To that end, special days of racing and other events were held as benefits for the park. In March 1887, such a benefit was held in the form of an entirely novel and modern spectacle: bicycle racing.

The Rise of Cycling in New Orleans

As in the rest of the United States and Europe, the very first bicycles, called “bone shakers,” appeared in New Orleans in the 1860s. These early models were so expensive that they were only accessible to the very wealthiest of citizens, as well as being heavy and cumbersome to ride. In 1869 and 1870, “velocipede” races were held at the Fair Grounds as novelty amusements for benevolent society picnics. Given the state of city streets, they were never practical as transportation and were relegated to specially built rinks as an indoor amusement. After a brief “craze,” they disappeared.

The first “high wheel” bicycles were brought from Europe to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. This new design consisted of a hollow frame and a large lightweight front wheel that allowed a rider to reach much greater speeds. Although difficult to ride at first, once a rider had gotten the hang of it these contraptions proved both useful for transportation on improved city streets and an intriguing new apparatus for athletic contests. New Orleans’ first adopter of this new bicycle, A.M. Hill—a prominent amateur athlete and wealthy jeweler of New Orleans, whose grand store stood at the corner of St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street—acquired his machine in 1880. A year later, he and a handful of other “wheelmen” formed the New Orleans Bicycle Club (NOBC).

The NOBC functioned as a franchise of sorts to the national cycling organization, the League of American Wheelmen (LAW) that formed in 1880, and began holding annual League tournaments for the LAW’s Louisiana Division in 1885. The first two meets were road races on the outskirts of the city in the West End and garnered little public interest. Cycling hadn’t quite caught on with the general public, and the format afforded no practical way for spectators to view the races.

In the spring of 1887, the NOBC came up with an idea, borrowed from cycling clubs of other cities: hold cycling races on a horse racing track. They chose the erstwhile Exposition Track, now called Audubon Driving Park, as their venue and held a cycling tournament to benefit Audubon Park.

In this sketch from the Olmsted Brothers landscape architecture firm, designers of Audubon Park, the track site is visible in green in the northeast corner of the park. Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

The Wheelmen at Audubon Park

Despite the fanfare in the press leading up to the event, this first cycling tournament at Audubon Park, in March 1887, was not well attended. As the year progressed, however, cycling’s popularity in New Orleans grew, especially with the young men of the Uptown bourgeoisie, as bicycles became more affordable. The Daily Picayune published a lengthy article that July on the rise in cycling’s prominence as both recreation and sport. “The recent asphalt pavement on St. Charles [A]venue has given new life to wheelings, and every afternoon and evening the avenue is crowded with wheelmen speeding to Carrolton and West End and other places of interest in the vicinity of the city.”

Interest in bicycle racing was also on the rise nationally. As The Picayune quoted from another paper, “A bicycle contest has largely become the people’s choice, close upon if not rivaling the horse race . . . for a contest of these beautiful steeds, the will-‘o’-the-wisps of modern speed, is indeed one of if not the finest of sights in American sports.”

In that same month, a sharp-witted teenaged railroad clerk named Richie Betts organized the Louisiana Cycling Club (LCC). Compared with the NOBC, this second cycling organization presented a youthful ethos, attracting the office workers and students of the Victorian middle class, who used bicycles as a means of transportation between their suburban homes and their occupations in the business district. Betts had a knack for public relations, penning lively missives on club activities to The Daily Picayune in a successful effort to drum up membership to his club and court public interest in the sport of cycling.

When the time came to hold the 3rd annual tournament of the LAW’s Louisiana Division, in September 1887, the NOBC and LCC worked together to secure the Audubon Driving Park as the venue. This time the turnout was far better—an estimated 4,000 people. To the surprise of the wheelmen, three-quarters of the attendees were young women. One member of the LCC wrote, “During one promenade past the grand stand, I was sure I had met my fate at least eleven times. Two of the boys withdrew from nearly all the races they had entered, and I verily believe the host of pretty girls was the cause.”

For the next few years, the annual cycling tournaments at Audubon Park were one of most important social events of the year, propelling cycling into the 1890s as one of New Orleans’ most popular spectator sports.

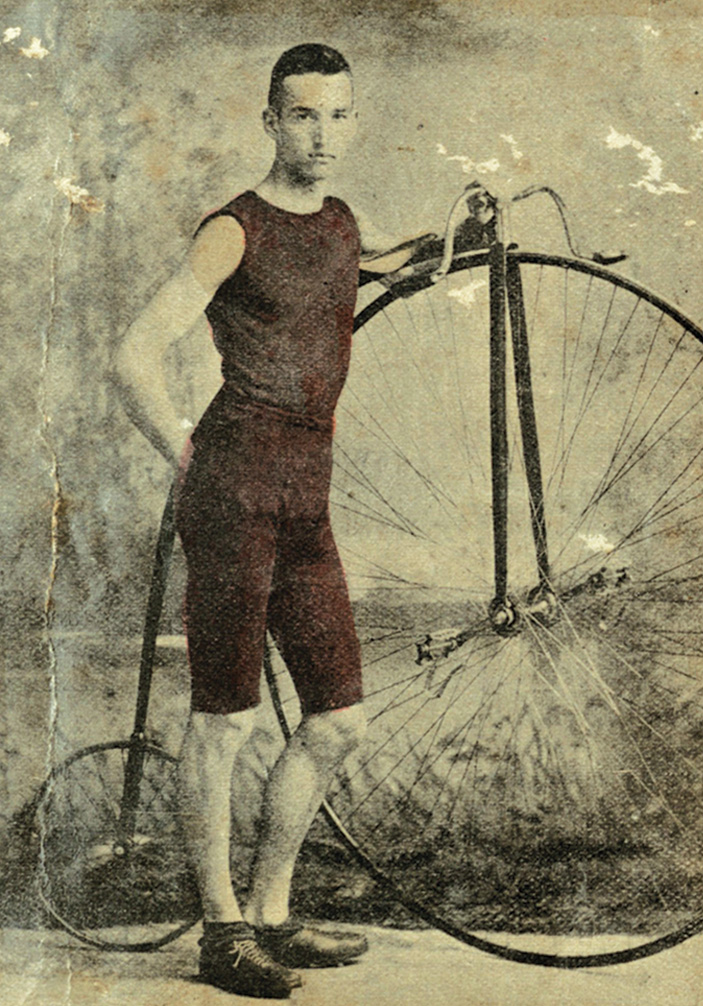

A cyclist poses with a penny-farthing, also known as a highwheel. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

Demise of Audubon Driving Park

The LAW tournament was held at Audubon Park for the last time in the fall of 1890. This was the first tournament of the newly organized Southern District League, as the national LAW had broken up the country into five racing districts that year. What precisely happened to the grand stand at Audubon Park is lost to history, but according to the mournful musings of The Tulane Collegiane in 1891, it was destroyed that winter. (The first spring games of the Tulane Athletic Association had also been held there, from 1887 to 1890.) The cyclists would find a new venue for their races at the Fair Grounds, but they lamented sorely the loss of their beloved original venue. As one wrote:

“What sad thoughts are suggested to one who gazes on the ruins of the Audubon Driving Park track, that familiar place where four of the most successful race meets have been held, the wreck of the immense grand stand upon which thousands of the fairest daughters and interested mothers have gathered to witness their brothers and sons contesting for glory and fame on their winged wheels . . .”

—–

Lacar Musgrove is a writer and historian who lives in New Orleans. She holds a BA in English from Boston University, an MFA in creative writing, and an MA in history, both from the University of New Orleans. She is the world’s leading expert on late 19th century cycling clubs in New Orleans.