Shreveport Sluggers

The history of professional baseball in Shreveport

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

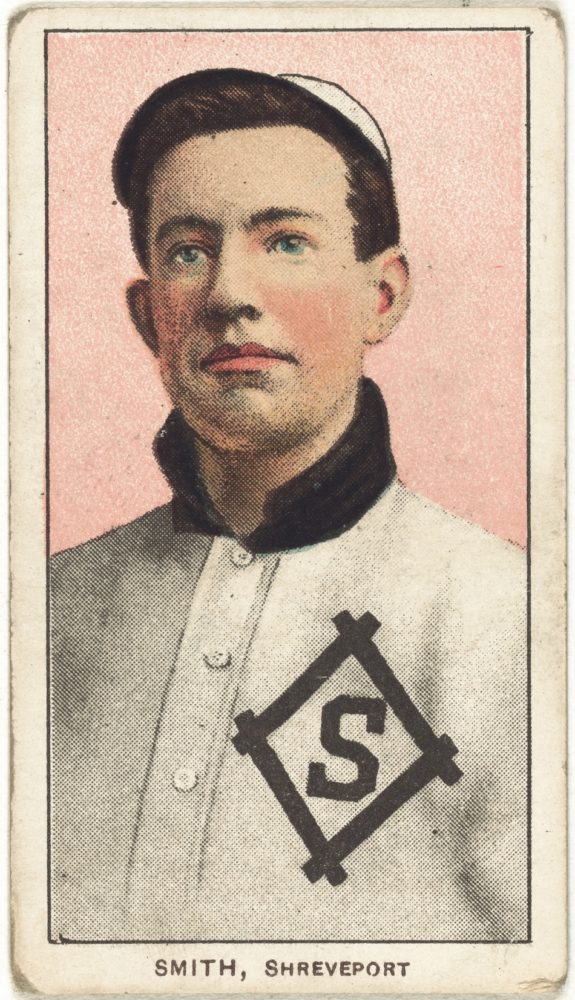

Benjamin K. Edwards Collection, Library of Congress

American Tobacco Company baseball card of Carlos Smith, a Shreveport Pirate in 1909–1910.

By 1895 the Shreveport Grays were active in the Texas–Southern League along with seven teams from Texas. However, as was commonplace during the tenuous early days of baseball, four teams, including Shreveport, fell upon hard times and disbanded by mid-summer, and the league collapsed. Three years later the Grays were back and holding their own in the Southwestern League at 58–38 when the league ceased operations in the late summer.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Shreveport became an inaugural member of the Southern Association and embarked upon a new and notable era in baseball with a team first known as the Giants (1901–1903) and then as the Pirates (1904–1907). The city fielded a succession of winning teams in the Texas League beginning with the Pirates (1908–1910), the Gassers (1915–1924), and finally the Sports (1925–1961, with some gaps). During this time Shreveport became firmly situated in the national baseball landscape. Following their 1919 Texas League championship under legendary manager Billy Smith, the city played host to Babe Ruth and the vaunted New York Yankees during their spring training camp in 1921.

The period from 1925 through 1961 was the heyday of the Shreveport Sports. Their popular club garnered Texas League championships in 1942, 1952, and 1955. They would claim three more championships between 1990 and 1995 as the Shreveport Captains, with a final title coming in 2010 in the American Association as the Shreveport–Bossier Captains.

Like scores of other cities across the country, Shreveport reveled in its time in the spotlight and was an integral and vital member of the national minor league system, whose defining characteristic is that their players are either on their way up to, or on the way back from, the major leagues. The parade of talented players that passed through Shreveport over the years is remarkable.

In 1908, a twenty-year-old Zack Wheat starred as Shreveport’s boss flycatcher before embarking on a seventeen-year career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Then there was Bill Terry, who was Shreveport’s first baseman in 1916 and 1917 before moving up to the majors for the next fourteen seasons. Outfielder Al Simmons patrolled the gardens of Gasser Park in 1923, then spent the next twenty years in the majors, including three All-Star Game and two World Series appearances. And human hit-machine George Sisler compiled 2,812 career hits during fifteen years with the St. Louis Browns and the Boston Red Sox before coming to Shreveport in 1932 as their player–manager. For Wheat, Terry, Simmons, and Sisler, the road to baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, ran through Shreveport. But they are only four of the thirty-seven notable Shreveport veterans who spent time in the major leagues. Others include such fan favorites as Tony Peña, Chili Davis, Dusty Baker, Rick Honeycutt, Rich Aurilia, and Joe Nathan.

Unfortunately, in 2011 Shreveport came face-to-face with the underlying economic realities of minor league baseball. The franchise was sold and relocated to Laredo, Texas. Declining attendance was a by-product of an endless turnstile that sent the team’s best players up the line from AAA to the Show. Fans did not always have the time to become familiar with players before they were gone. Today’s business model consists of extracting more and more revenue from smaller stadiums with lower ticket prices, while player salaries for those not included on the team’s forty-man roster are only sometimes paid by their major league affiliates. In a world of rising operating costs, this strategy faces stiff competition for the consumer’s entertainment dollar. Bearing in mind that baseball is a game of failure—even a good hitter is only right less than one-third of the time—many communities are constructing new baseball stadiums as the centerpiece of their revitalization efforts.

Does this strategy work? For those communities that survive the sticker shock of capital improvements and are willing to accept the risks, the answer would be affirmative. Neighboring states that have thrived in the current economic environment include Texas, with two major league and fourteen minor league teams, Florida, with two major league clubs and a staggering thirty-two minor league teams, and five other adjacent states with twenty-five minor league franchises between them. But consider this: the Shreveport Captains played their final season in 2011 and the Baby Cakes left New Orleans at the end of the 2019 season for Wichita. Louisiana is now one of the largest states in the country without professional baseball at any level. Fair Grounds Field in Shreveport now sits empty, home to a colony of endangered bats that makes updating the ballpark difficult.

The future of professional baseball in Shreveport and New Orleans has become more complicated by the recent proposal from Major League Baseball to reduce minor league baseball by as many as forty-two teams by the end of the 2020 season. Such a move would not only devastate smaller communities but would also diminish the value of surviving franchises. If this proposal is accepted, cash-rich major league franchises could acquire the devalued minor league clubs for a fraction of their worth, and smaller communities will think twice before expending millions of dollars on facilities. As baseball’s 2020 season gets underway, baseball fans in Shreveport can commiserate with their counterparts in New Orleans in wondering if the current state of baseball has passed them by or if their communities will ever get another shot at hosting a minor league team. Indeed, the National Pastime is in peril not just in Shreveport and New Orleans, but throughout America.

S. Derby Gisclair is a sports historian and author.