Disturbance in Your Mind

Sinister Scenesters

A brief history of Process Church's time in the French Quarter

Published: March 8, 2017

Last Updated: November 2, 2020

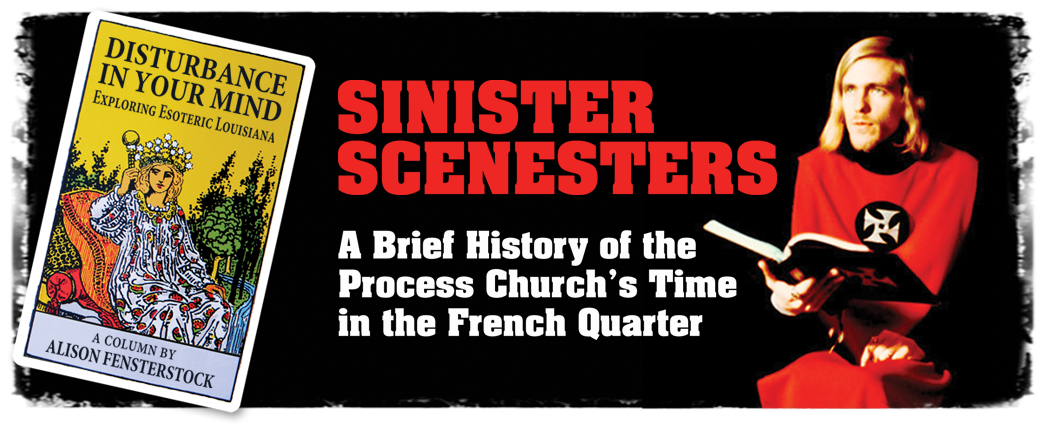

Father Christian, aka Father Gabriel, reads the Holy Missal. From: Love, Sex, Fear, Death: The Inside Story of The Process Church of The Final Judgment.

Between the late fifties and the mid-sixties, L. Ron Hubbard presided over the fast-growing worldwide Church of Scientology from an eighteenth-century manor house in Sussex, about an hour’s travel from London. Among the Britons attracted to the movement’s eccentric teachings were Robert Moor, a young architecture student at the Royal Polytechnic Institution in London, and his future wife, a Glasgow native named Mary Ann MacLean. MacLean in particular seems to have excelled at Scientology coursework, soon becoming an auditor—a counselor leading one-on-one sessions with “preclears,” or beginner Scientologists—but after less than two years, the couple broke with the group. They had not, however, lost interest in the idea of an alternative route to psychological and spiritual growth and developed a therapy technique called Compulsions Analysis, which was modeled in part on auditing and also made use of the E-meter, the polygraph-like device Scientologists employ during auditing sessions. (The off-label usage got Moor and MacLean declared Suppressive Persons—toxic personalities to be avoided—by Hubbard himself.)

Moor and McLean changed their last name to the rather lordly and mystical-sounding de Grimston and set up shop in swinging London, where Compulsions Analysis morphed into the Process Church of the Final Judgment and took on, as the new name implied, a more faith-driven tone. The Process’s theology was based around a trio of god figures, Jehovah, Lucifer, and Satan, plus their emissary Christ. Each, as an archetype, represented different personality elements that acolytes, of which there were soon many, might identify with. The Processeans produced radio and TV shows, as well as newsletters, books, and magazines espousing an increasingly apocalyptic philosophy that members sold in the streets as they proselytized to potential converts and donors. They spent the rest of the sixties and seventies moving from London to Nassau to Mexico to the United States, eventually establishing chapters in multiple cities throughout Europe, the United Kingdom, and Canada—and in 1967, they set up shop in New Orleans.

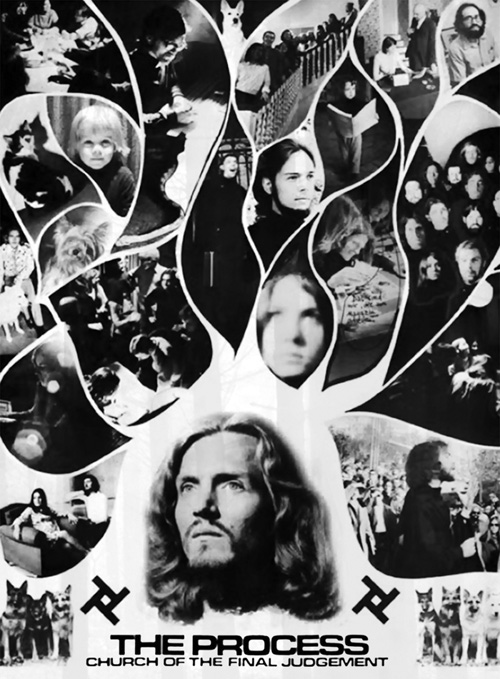

An image from Love, Sex, Fear, Death. Courtesy of Feral House

The de Grimstons, who were known together as the Omega, settled into a house in Slidell, but the bulk of the church’s activity took place in the French Quarter, in rented spaces on Royal Street and later, at 627 Ursulines Street. Even in their distinctive black and purple robes, ornamented with big, clunky pendants in the shape of four interlocking stylized P’s, rather evocative of a swastika, they fit in well to the colorful French Quarter scene of the late sixties, which was rife with bohemian activity.

They even had competition in their evangelizing. D. Eric Bookhardt, the New Orleans art critic and photojournalist, was a philosophy major at the University of New Orleans at the time and living in the Quarter, where a group called the Bodhi Sala—Buddhists with a psychedelic bent—had established a stronghold among hippie seekers before the Processeans arrived. The Bodhi Sala were “LSD Buddhists with a strongly localized flair, a much more cohesive, community-grounded organization [than the Process],” Bookhardt recalled. “Their rituals were always great parties in the French Quarter, ostensibly religious rituals with drumming and dancing into the night, it was great. The Process was clearly a much more sinister invasion, uptight acid-freak would-be messiahs. They weren’t very successful in recruiting; they didn’t have any of the grassroots appeal Bodhi Sala had.” He liked the main Processeans he met—Englishmen Hugh Mountain and Timothy Wyllie, the art director for Process publications, who published a memoir of his time with the cult in 2009—well enough, but wasn’t sold on the teachings.

“Their unity of Satan, Lucifer, and Jehovah philosophy was really a just simplistic rehash of Carl Jung,” he said. “But I think they liked the theatrics of the nomenclature.”

The Process Church incorporated in New Orleans in 1967, though the Omega and other core members continued to travel the world setting up new chapters. Whoever was left in New Orleans apparently continued to do fairly standard church work: mentions of the Process in mainstream local news from the early seventies include a party for patients at a children’s hospital, a Thanksgiving meal served to the needy, and a Christmas caroling party. According to Wyllie’s book, Love Sex Fear Death: The Inside Story of the Process Church of the Final Judgment, the de Grimstons—living just outside New York City at the time—divorced in 1975, and Robert returned to New Orleans alone to focus on hosting seminars. A 1977 brief in the Times-Picayune advertised Process-run courses on hypnotism, nutrition, t’ai chi, and “life after death” at the Ursulines Street address. Around the same time, the church was listed as a resource for substance abusers in an ad sponsored by Whitney Bank.

Glasgow native Mary Ann MacLean and partner Robert Moor brought the Process Church to the French Quarter.

The Process did have a couple of tenuous connections to Charles Manson. One, Wyllie notes in his memoir, was that the church’s chapter house in San Francisco was only a few blocks from Manson’s known address there at the same time, in early 1967. “This unhappy coincidence has long fed the conspiracy theorists,” Wyllie wrote. Less coincidental was the fact that in its 1971 Death issue, the Process magazine published an interview with an imprisoned Manson. “After all, we naively reasoned,” he wrote, “wouldn’t he have some extreme comments to make about death?”

The magazines, full of such interviews and Robert de Grimston’s esoteric writings, maintained a steady pop-culture cult interest for decades. Maybe most famously, the 1971 Funkadelic album Maggot Brain has a long excerpt from the Fear issue as its liner notes. Much later, in 1996, Skinny Puppy released a concept album, The Process, based on the group and its teachings. The musician and performer Genesis P-Orridge had introduced the band to the Process; he’d drawn heavily himself on its ideology when conceiving his own artistic/occult collective Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, or TOPY, in the eighties. P-Orridge contributed an essay to Love Sex Fear Death—which took its title from different Process magazine themes—as well as to a follow-up collection from Wyllie’s publisher Feral House reproducing several issues of the magazine, which, besides the dramatic written content, was notable for trippy, innovative design courtesy of the core Process team’s architecture-school graphics skills. (Forty years later, Eric Bookhardt, the art critic, remembered the style as “quite brilliant,” explaining over email, “[It] employed some sort of color saturation technique that Tim developed for its psychedelic fascist art nouveau graphics that was fairly innovative for the time.”)

After establishing chapters throughout Europe and the U.K., the Process Church set up shop in New Orleans in 1967.

Several active Facebook pages and a website exist today under the name The Process Church of the Final Judgment. The original entity changed its name multiple times after it first officially incorporated in New Orleans in 1968, becoming, in chronological order, the Foundation Church of the Millennium, the Foundation Faith of the Millennium, and the Foundation Faith of God before it arrived at its current official title: the Best Friends Animal Society. In most reports about the group, the multiple German shepherds kept by the members at any given base are a recurring detail, cast in some as a sinister one. Many more in-depth accounts, though, reveal that alongside their end-times philosophy and four-sided Judeo-Christian godhead, the Processeans were simply devoted dog lovers. Wyllie’s book in particular contains several stories about the antics of his beloved dog Ishmael who, like many Process dogs, were subject to therapeutic counseling sessions based on the Scientology-derived techniques the cult used for humans, but (necessarily) modified. “Unlike sessions for the humans,” Wyllie wrote, after therapy “there was no period for discussion.”

Because the Best Friends Animal Society simply changed its name instead of incorporating as a new business, it was easy to link to its odd origins, and in 2004, the Rocky Mountain News published a lengthy, rather amused-sounding article about the whole thing. Eric Bookhardt’s old French Quarter acquaintance Hugh Mountain, who had changed his name to Michael Mountain, was quoted in it as the president of Best Friends, headquartered on several thousand acres in southern Utah. The group is still based on the same land, which is open to tourists (the Best Friends Animal Sanctuary has 980 reviews on TripAdvisor, with an average 5-star rating) and is, according to its website, the nation’s largest sanctuary for homeless pets, offering spay-and-neuter services and adoption.

At the time of the Rocky Mountain News feature, Mary Ann de Grimston, who had remarried (to another longtime Processean) was living in a house on the sanctuary’s land. She passed away the following year—just two months after the group returned to its old stomping grounds in New Orleans, to help pets affected by Hurricane Katrina.

Alison Fensterstock writes about American culture for outlets including NPR, Pitchfork, the Oxford American and others. She has served as the music critic for both Gambit and the Times-Picayune in New Orleans and was the founding program director for the Ponderosa Stomp Foundation.