Magazine

Southern Journey

During the Civil Rights years, blacks had achieved the miraculous by kicking open the doors — but once inside, well, there was hardly anything there

Published: February 16, 2016

Last Updated: January 31, 2019

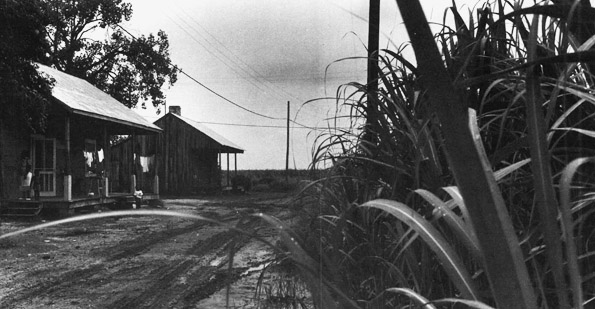

Photograph by Chandra McCormick, 1984.

"The Quarters," Ashland Plantation, Port Allen, River Road, Louisiana.

Then my father would head for the river at the foot of Canal Street. Here, at the docks, right beside the Louisville and Nashville train station, he would park and we would get out. I always raced to the edge of the dock to stare at the strange muddy currents of the river, which was wide enough to be a lake. I would look upriver and downriver, to the very edge of its sharp bends, as if I might fathom the past hidden beyond the curve downriver, the future upriver. To me, the river was the oldest living person in New Orleans. It was the great highway out into the world beyond the street comers, beyond the limitations and boredoms of the world I was growing up into. The sound of austere ships’ horns was enough to trigger my imaginary trips to more exciting places, for I knew the great river led to anywhere and to everywhere.

So did the sound of train whistles -in my early dream world, trains always ran beside the river, leading to more certain and appealing destinations. For me and others like me, those dream roads -fueled by books, movies, and legends -led to a nonracial world, where the color of our skin, our racial heritage, did not matter. But then, that was truly a dream world -a world, I have come to believe, that does not exist.

Those dream roads – fueled by books, movies, and legends – led to a nonracial world, where the color of our skin, our racial heritage, did not matter.

As a boy going to school in New Orleans in the late 1940s, I had had to sit in the rear of streetcars and buses behind a movable wooden barrier with the words For Colored Only stenciled upon it as if some sort of privileged section had been set aside for us. We were to sit in the first car of trains, in the balcony of movie theaters, and on the main commercial street, Canal Street, we were waited upon at the side counters of restaurants like the one in Woolworth’s. We had to master a knowledge of where the “for Colored” bathrooms were at the downtown stores, and which businesses maintained them, however poorly; where the “Colored” water fountains were, which stores we might enter, which places we must never enter, certainly not through the front door. If a large auditorium or waiting room served the entire public, we must know, as if by special divination if no sign existed, exactly where we must sit. For fear of the everroving police, we had to know for our own protection which streets to walk, which never to tread upon, which never even to ride through on our bicycles. Growing up with this was a burden, but a little bit laughable because it was so ridiculous. Defying these rules and restrictions, if we could get away with it, increased our, and my, pleasure. This maze of restrictions created a certain psychological racial solidarity; for no matter how well off we were, or how poor, each of us was proscribed by the same rules.

We didn’t think, or talk about, a mass rebellion, or active, deliberate, conscious resistance to these obstructions. Individuals, fed up or too egregiously insulted, did, from time to time, of course; they were jailed or worse. The attitude passed down from elders was: We should make out the best we could under the circumstances; someday a better time would come.

These were my own conclusions. My father was not one who enjoyed being asked “why” when it came to racial matters. You were supposed to become aware of the more subtle and unpleasant vagaries of race via osmosis. I eventually took to calling such undiscussed racial patterns “blues truths.”

A large part of why I remained in the South has to do with my experiences in Mississippi in the late 1960s. In Mississippi, I was able to experience more completely the civil rights movement, and learn what made it successful. The impetus for social change was rooted in a few courageous people, most of whom were black, some of whom were white, who were building upon the lonely spadework done by leaders from previous generations extending back to Emancipation. The sixties, including the civil rights movement, were an eruption of energy that had been building for some time.

I decided to undertake a long, and very possibly insane, leisurely drive through the South over a period of several months. My intent was to interview people in small towns or cities that experienced trauma over civil rights conflicts or racial disputes in the sixties or the period immediately following.

I decided not to confine my interviews to civil rights history, but to search out people’s impressions of their towns–as places to remain in, leave, or return to. I knew I would be talking mostly to blacks; they were the ones whom sudden change had most profoundly affected. I intended to talk to whites also, particularly newspaper people, who I believed were generally knowledgeable and relatively objective. I also knew that the views of Southern whites on race had received, and continue to receive, considerable exposure.

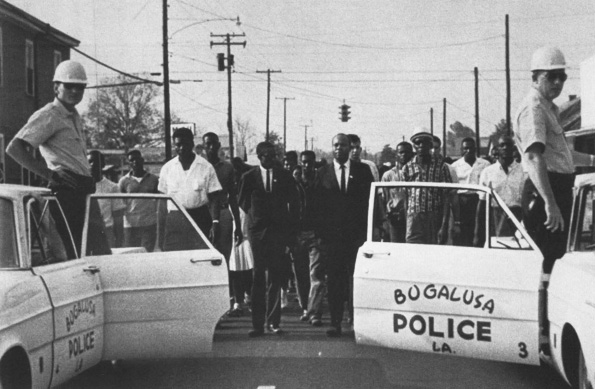

Civil rights march, Bogalusa, Louisiana. Courtesy of the Ronnie Moore Collection, Amistad Research Center at Tulane University.

Linking Past and Present

I headed for the tiny, all-black town called Mound Bayou, on U.S. 61 in the heart of the Delta, to see L.C Dorsey, who was administrator of the Delta Heath Center. Ms. Dorsey, now in her fifties, the mother of six children who has recently earned her doctorate in social work

L.C. Dorsey is truly a child of the Delta. Short in stature, but passionate in her convictions, she is one of the great Mississippi success-through-struggle stories. “I grew up living in four counties,” she told me, “Bolivar, Washington, Sunflower, and Leflore. I went to high school in Drew but never graduated.” Eventually, she ended up at the Stony Brook branch of the State University of New York, and enrolled in a social welfare program, where she wrote a paper on women incarcerated in Mississippi’s Parchman Penitentiary, the huge, infamous state prison. Back in Mississippi for a period, she worked in Head Start, attended the University of Mississippi Law School for a year, wrote articles for Charles Tisdale’s black weekly, the Jackson Advocate.

I first heard of L.C. Dorsey when she worked for the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, monitoring complaints at Parchman Penitentiary, a job she held for eight years and performed with such tenacity that her investigations and the legal suits that ensued virtually transformed the brutal Mississippi prisons into an acceptable modern system. Her doctorate is from Howard University, her dissertation on prisoners who had killed their mates.

I drove the fifty miles to Mound Bayou on US 61 from Leland, just a few miles east of Greenville, passing through Shaw and Cleveland. By now most of the cotton was picked and the plants were cleaned from their fields.

“We’re suffering,” Ms. Dorsey began, as we talked in her health center office, “from the demise of a sense of community. What used to hold us together was apprehension–churches, families, and extended families offered help to people in need. These were the units of community survival. The last time I remember this kind of support system existing was during the civil rights movement. Somehow our sense of family has broken down, felt all the more painfully in desolate areas like the Delta. Welfare was destructive because it forced women into a dependency role. Then there was housing built outside the inner cities, which broke up the neighborhoods. Recently, I moved back to the town of Shelby [just north of Mound Bayou]. But I don’t know people on my block. All this is new.

I could feel the spirit of the people who had once worked this land and have left, splintering families and memories.

“Now I worry about crime in a way I never did before. Crime is directly connected with unemployment, but there is also an alienation among young people -a concern with the materialistic: cars, sneakers, clothes. Drugs have accentuated this process by clouding and obscuring the concepts of success.

“What we have is a new group of people who have become dross. The prisons are their intended future, new and ever more glorious prisons, especially for young black males. Once,” she remembered, “I was visiting Parchman just a few miles from here on U.S. 49. These visits were always difficult because it was so painful I hated to go, and I heard prisoners laughing, enjoying themselves. It made me mad that they were laughing, when I felt maybe they should be crying. I asked Dwight Presley, who is now an associate warden, ‘Why are these people so happy in here?’ He answered, ‘You don’t realize. There’s whole families in here; they’re happy when they see each other.’ They’re also happy when they have a certified role in society, as criminals or prisoners, the natural conclusion to how they have been treated all their lives.”

“I agree with all that, L.C.,” I said. “Everything I’ve seen on this trip confirms those impressions. But what can we do to change some of this?”

“All I can see,” she replied, “is that our salvation has to come from looking back at what we’ve done in the past that worked. We’ve got to do something for ourselves; those of us who see what’s happening have to take more initiative. For one thing, we have to put money back into the black community. And we’ve got to do a better job with the education of our youngsters, both in and out of the public schools.”

Taking an Account

As I drove back down US 61 headed for Greenville, then over to Mississippi 1 and the Mississippi River, southward to Mayersville, where I would meet Unita Blackwell and bring this nine-month odyssey through the South to a conclusion, I reflected on the issues L.C. Dorsey had brought up. I felt there was a need for new, specialized organizations to deal with today’s complex issues of education, unemployment, drug abuse, and crime, and to monitor political officials, white or black. Relying on the NAACP as a catch-all was passe’. It seemed as if the black community in the South, which had been the brave protagonist for change in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, had now fallen behind, become less aggressive, and less able to assess what had happened after the momentous changes, or exchanges, of the ‘70s and ‘80s, had occurred. It was now time to take account.

As I drove southward into the waning day, I could see the moon rising above the fields; in the Delta the land is so awesomely flat. US 61 parallels the railroad tracks, the same railroads that help make so much of the agricultural South profitable, the same railroads that carried people away from these lands once they were no longer profitable. I flipped on the radio and picked up a blues music program from Clarksdale, twenty-five miles north of Mound Bayou. Somehow, through the force of that music, so much of it about parting and leaving, and the wistful sound of train whistles, the roaring rhythm of train wheels, I could feel the spirit of the people who had once worked this land and have left, splintering families and memories.

In my own family, on my father’s side based in Georgia, I could hardly trace my ancestors back beyond my father’s mother. My mother’s Texas roots were torn up, too. There was nothing left of her mother’s old village of Cheapeside, on the outskirts of Gonzales. Sure, some of the same structures were still there, the wind blowing through them, but there were no people. They had all died or left -endlessly searching for the ever illusory betterment of conditions–to California from Cheapeside, to Chicago from the Mississippi Delta.

On my mother’s side there was the legendary figure of my great-grandfather, Ben, the furthest we could go back into our hazy past. We had heard he was a stagecoach driver between Oklahoma and Mexico. It was his spirit, I had come to accept, that had possessed me, and was driving me along all these southern roads-from North Carolina to the Mississippi River. I shared with Ben a compulsive yearning for wandering. Now, amazingly, these fields I was driving through gave me a feeling of security, of at least temporary rest, as they have for so many others, particularly those of African descent. Can any of those people ever really be from Chicago, Detroit, or New York City? I didn’t think so.

Changing Positions

Mississippi 1 south of Greenville is one of the most isolated highways in the South. After about fifty miles I reached the Mayersville turnoff, a westward turn on Mississippi 14 that goes straight to the Mississippi River. There was not a soul in sight, hardly a farmhouse and no cars coming the other way.

Suddenly, a village appeared a mile or so ahead, a mirage it would seem. When I reached it -all one quarter of a square mile of it with its population of 475 persons–it was Mayersville. Behind the town is the Mississippi River levee and after a half mile or so of batture, the river itself.

The town exists because of the river. Before the Civil War Issaquena County was one of the most prosperous areas of cotton and slave plantations, with huge numbers of slaves per owner, more than any other area of Mississippi. In 1851 Issaquena was home to the largest plantation in the Delta, with more than 700 slaves, according to James C. Cobb in The Most Southern Place on Earth. A river· port was built to export the abundance of cotton.

One hundred years later the population of Issaquena County is only 1,730, of Mayersville only 475, the port forgotten. The town consists mostly of blacks and a tiny number of whites. The county courthouse is still in this settlement.

In the early 1960s when SNCC workers showed up in this forgotten place, one of the first blacks they talked into attempting to vote was Unita Blackwell, then in her late twenties, a cotton picker married to a native of the county, with not even a high school education.

Despite her lack of education, Mrs. Blackwell was brilliant and aggressive. Turned down when she first attempted to register, she appeared at the courthouse again and again, along with a few other independent blacks who braved the inevitable threats, until they were added to the rolls. For her impertinence she was told she would never again work in the cotton fields, which was about the only work available. Tall, dark skinned, full of wit, and using her own unique version of English, which is more expressive than standard English, Mrs. Blackwell decided to go to work for SNCC. She became one of its most effective organizers.

During the post-Movement years, she worked with Owen Brooks and Harry Bowie under the aegis of the Delta Ministry to incorporate Mayersville. This they did in 1976. The following year she was elected the town’s first mayor.

I met Unita Blackwell and her family at her new brick home located not far from the cotton fields where she used to pick. “All we need now,” she said, “is some work here in this place. We’re trying to lure a factory.”

“Where do the people work?” I asked. There were no businesses in town except for two service stations, two stores, one owned by a black, the other owned by a white, and a new sandwich shop owned by a black man. City hall was a converted church.

“In Greenville, unless they own their own land, or wherever,” she sighed.

“But still you like it here?”

“Yes, indeed. I love it. So peaceful this place. And then there is the river. Who wouldn’t want to live by the river? I can go anywhere in the world and return here and feel at home by this river.”

I loved it, too; Mayersville is the most beautiful, isolated, and out-of-the-way place in the entire South, for sure; Mrs. Blackwell had become mayor of a dream town.

“I’m only mayor,” she reminded me. “I can’t work miracles.” She certainly can’t be expected to, though she herself was something of a miracle. As we spoke, I thought about how her story was like so much of what I had seen in my travels these past ten months: During the Civil Rights years blacks had achieved the miraculous by kicking open the doors -but once inside, well, there was hardly anything there. It was almost laughable, a kind of special “blues truth.”

“Let’s go drive over to the river,” I suggested to her. We got into my car and headed for the gravel road that would take us over the levee. As we were passing the county courthouse, I asked Mrs. Blackwell if she had ever discussed the old days with the county registrar, the woman who had denied her the right to vote until Unita wore her out, and who also lived in Mayersville.

“Oh, yes. I talked with her. She said, ‘That’s the way we were brought up, Unita. That’s the way things were then.’”

As we approached the river, a perfectly pristine scene, I asked, “What did it all mean, do you think?”

“Well, we didn’t gain much,” Unita admitted. “We changed positions. The river changes positions; it’s constantly moving, you know, taking on new routes, cuttin’ off old ones. It may not look like it, but it is. Any powerful force will make a change. I suppose what we really gained is the knowledge that we struggled to make this a decent society, because it wasn’t. And maybe it still isn’t now, but at least we tried. That’s history.”

——

Tom Dent (1932-1998) was the executive director of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation. He is the co-editor of The Free Southern Theater by the Free Southern Theater and the author of two volumes of poetry, Magnolia Street and Blue Lights and River Songs. This article was excerpted from Southern Journey: A Return to the Civil Rights Movement (William Morrow & Co., Inc., 1997), a book about Tom Dent’s journey through the contemporary South revisiting the places where protesters took a stand. He interviews civil rights workers and just plain folks about the events that shaped the Movement and the impressions these events left on their communities. Used with permission of the author.