Winter 2007

The Dodds Brothers

Baby and Toilet outshone their names

Published: June 16, 2022

Last Updated: June 16, 2022

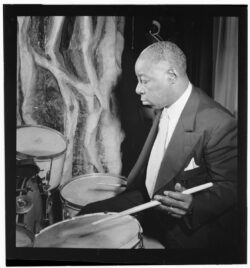

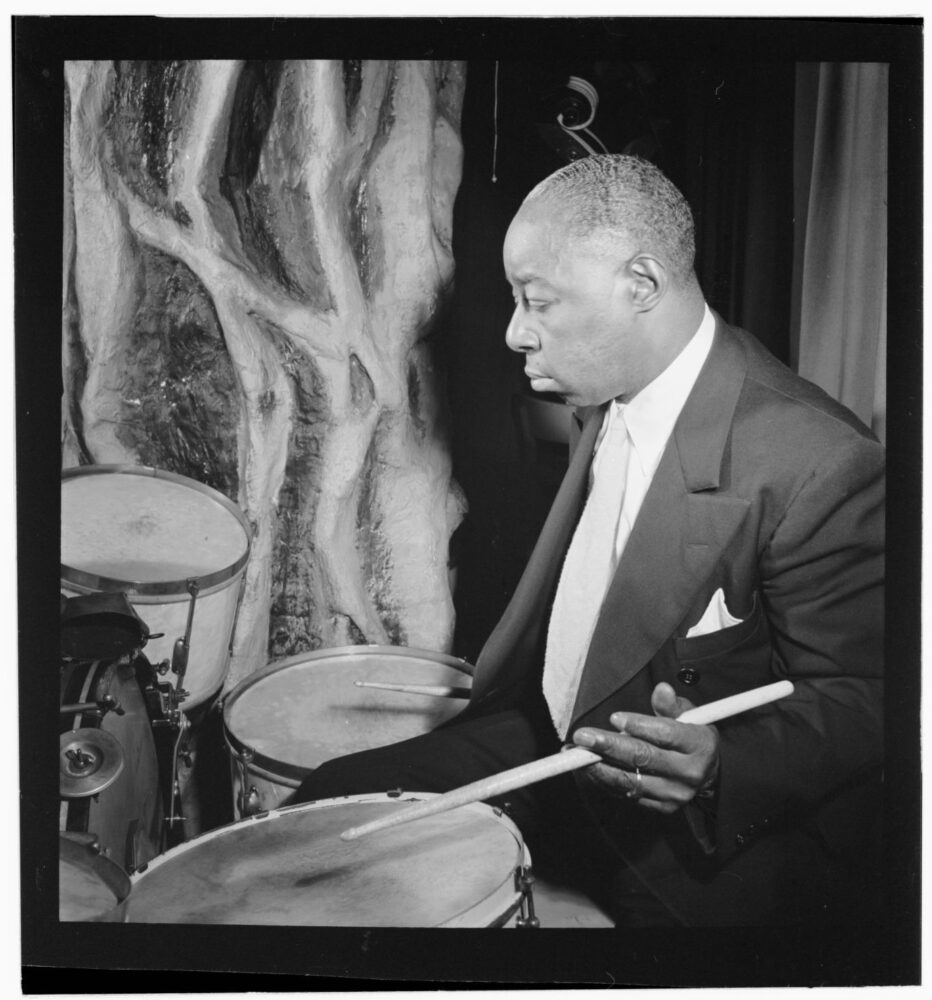

Photo by William P. Gottlieb, Library of Congress

Baby Dodds playing in New York, ca. 1946.

Yet somehow this nickname gets to the blues essence of what Johnny Dodds’s clarinet style was all about—evocatively self-expressive, with a refulgent roundness of tone across all registers of the instrument. What he lacked in technique he made up for with feeling. What set him apart was that he didn’t sound like any of the Creole clarinetists who came out of New Orleans in the early Jazz Age. He had a voice of his own, which is what every jazz musician aspires to. Baby, for his part, is often recognized as the first great jazz drummer through his associations with Kid Ory, King Oliver, Fate Marable, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and, ultimately, during a long stretch with his brother’s bands in Chicago in the latter 1920s and 1930s. Individually and as siblings, the Dodds brothers made unique and abiding contributions to the evolution of traditional New Orleans jazz.

Johnny was born in 1892 and Baby a little over six years later. As children, they got their first taste of New Orleans’s “hot” music chasing the second lines in Central City. Johnny started on a tin flute obtained from a bottle man, while Baby built a drum for himself from a lard can, fashioning sticks by whittling down rungs from one of his mother’s chairs. (First person to sit in that chair after Baby got through with it was definitely in for a surprise!)

Individually and as siblings, the Dodds brothers made unique and abiding contributions to the evolution of traditional New Orleans jazz.

When the family moved to Waveland, Mississippi, probably around 1909, Baby brought the lard can and used the baseboards of an outhouse in the back of their cottage as his bass drum, achieving what he called a “big sound.” So big, in fact, that when he asked his father for a drum set for Christmas (after Johnny had received a real clarinet to replace the tin flute), he was informed that he was “making enough noise already.” So much for spoiling the Baby! Soon after he went to work in a bag factory back in New Orleans to get the money to buy himself a drum set and paid for lessons from Dave Perkins, Louis Cottrell, and Walter Brundy. Looks like “big brother” Johnny caught all the breaks: the only downside for him was that wherever he went, Baby was sure to follow.

And follow he did. Thus the two brothers were paired in Kid Ory’s band, with Marable on the Streckfus Steamers, in King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, with Louis Armstrong’s Hot Seven, in Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers, and in Johnny’s Black Bottom Stompers—a list that accounts for many of the classic jazz recordings made in the 1920s. To the very end, Johnny never could shake his younger brother. After his brother’s death in 1940, Baby went with Bunk Johnson and rode the New Orleans Revival to even greater international celebrity with recordings of his drum solos and radio programs such as Rudi Blesh’s This Is Jazz. Both Gene Krupa and Dave Tough—two of the most highly regarded jazz drummers of the Swing Era—learned the basics of tuning and playing drums “hands on” from Baby Dodds, who once said: “Some people call [the way I play] ‘old style,’ but, if nobody else can do it, I don’t think it’s ‘old style.’” Like his brother, Baby found his “own voice” early on and kept it fresh for a lifetime. For him, jazz drumming was not about the notes or beats you played but the spirit behind them.

Examining the relationship of the Dodds brothers provides some interesting insights, because even though they worked together almost constantly for nearly twenty-five years, according to Baby they “couldn’t see eye to eye.” He described Johnny as very stern, although not without a sense of humor. As a boss he was strict, always insisting on punctuality for rehearsals, which Baby sometimes missed because he “drank a little.” Johnny didn’t drink, but he loved prize fighting. When watching a fight, he had a quick temper and would throw sympathetic punches, often striking the people adjacent to him, but “without malice” according to his brother. When King Oliver was touring in the 1930s he tried to lure Baby away from Johnny’s band, but Baby wouldn’t leave—he was steadfastly loyal. Johnny’s death must have hit him hard, and although he continued to perform with such clarinet luminaries as Sidney Bechet, Jimmie Noone, George Lewis, and Darnell Howard, the loss of his brother took some of the joy out of life for him. Baby passed in 1959, and Larry Gara’s The Baby Dodds Story came out later that year, based on interviews made in 1953. The book leads off with a quote from Baby that summarizes his views on the importance of the drummer in any band: “You can’t get into a locked house without a key, and the drum is the key to the band.” On second thought, maybe “latch key” Baby wasn’t so far off after all.

Bruce Boyd Raeburn, PhD, is the former director of the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University.