The Nile Comes to Bayou St. John

The New Orleans Museum of Art presents Queen Nefertari’s Egypt

Published: May 31, 2022

Last Updated: August 30, 2022

New Orleans Museum of Art

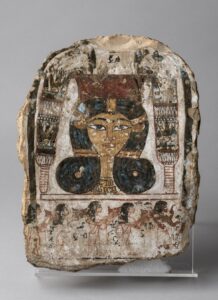

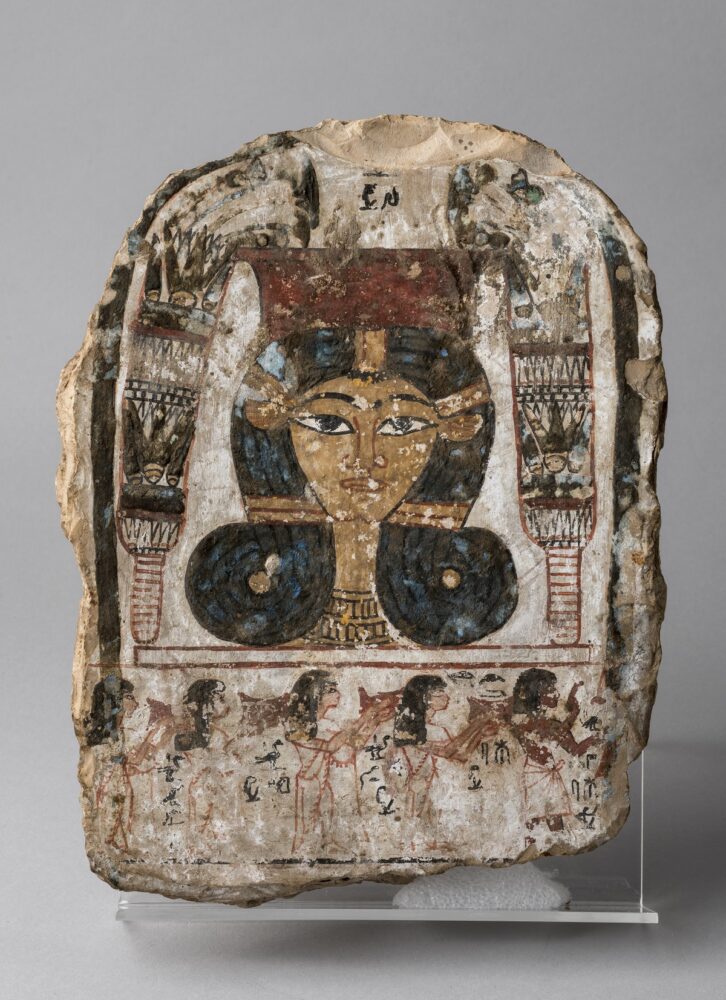

Stela with a Hathoric face. Painted limestone, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty (ca. 1292–1190 BCE).

The One for Whom the Sun Shines. Beautiful Companion. First Royal Spouse. These titles refer to Queen Nefertari, the great royal wife of the pharaoh Ramesses II (reigned 1279–1213 BCE), and one of the most celebrated queens of New Kingdom–period Egypt (about 1159–1075 BCE). Until the early 1900s, Nefertari was known primarily through large-scale sculptures embedded on temple facades, hieroglyphic inscriptions, and text-based sources related to Ramesses II. However, in 1904, the Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli, then director of the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy, rediscovered her tomb—the most richly decorated in the Valley of the Queens. Although the contents had been looted in ancient times, the remaining objects and the magnificent murals lining the tomb walls revealed the power, authority, and status of Nefertari and detailed the perilous journey she had to make on her path to immortality.

The lives of powerful women, including Nefertari, and other wives, sisters, daughters, and mothers of pharaohs, are brought to life in the exhibition. The extant objects from Nefertari’s tomb are on view, as are large-sculpture, votive stelae, papyri, painted sarcophagi, and objects for personal adornment from the New Kingdom period. Drawn from the collection of the Museo Egizio, the world’s oldest museum devoted to the art of ancient Egypt, Queen Nefertari’s Egypt casts light upon the belief systems of the New Kingdom period, including the roles of the pharaoh and the queens, and that of the gods and goddesses who dominated both ritual and everyday life.

An extraordinary group of objects from Deir el-Medina, home to the artists who made the tombs of the kings and queens of the New Kingdom period, is also on view. For over 500 years, this isolated village, nestled between the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, was home to scribes, sculptors, and other educated elites, who developed their own cultural and religious practices; it remains one of the most important sources of information for the lives of non-royal ancient Egyptians. These objects, whether utilitarian vessels, artist’s tools, jewelry, or papyrus documents of insurrection in the pharaoh’s harem, all survived due to the ritual practices surrounding death and the afterlife. Preserved by placement in rock-cut tombs and the arid climate, these objects have provided a measure of immortality for their former owners and creators.

Queen Nefertari’s Egypt is on view through July 17 at the New Orleans Museum of Art. noma.org.