Magazine

The Room Must Evoke Some Ghosts

Writing after Tennessee Williams

Published: March 15, 2016

Last Updated: April 30, 2019

Photo by Michael Brosilow

The cast of the Steppenwolf Theater's production of D'Amour's "Airline Highway."

This article was made possible by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a program to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Prizes in 2016.

Announced by the Pulitzer Prize Board, the Campfires Initiative aims to ignite broad engagement with the journalistic, literary, and artistic values the Prizes represent. The board partnered with the Federation of State Humanities Councils on the initiative and awarded more than $1.5 million to forty-six state humanities councils. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities received $34,000 to support articles in Louisiana Cultural Vistas and public programs around the state about Pulitzer winners with ties to Louisiana. On Friday, April 1, Lisa D’Amour joins Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Beth Henley, Williams scholar Thomas Keith, actor, director, and playwright Austin Pendleton, and moderator John Pope of The Times Picayune for a panel discussion at the Tennessee Williams Festival. Visit tennesseewilliams.net for more information.

I should remember the first time I read A Streetcar Named Desire. I should remember the first time I met Blanche DuBois, the uncertain moth, walking down Elysian Fields, completely at odds with her environment, her vulnerability conveying the entire world of this play to me — New Orleans refracted through the mind of Tennessee Williams. I should remember her arrival in the girls night out scene, the vibe of primping and perfuming suddenly interrupted by Stanley Kowalski: “How about my supper, huh? I’m not going to no Galatoire’s for supper!”

Is it strange that I don’t have that perfect, magic memory of experiencing the play for the first time? Or is it just because now, 20 years into my writing life, Streetcar is simply a part of my DNA? Almost like it has existed since the beginning of time?

I am a fifth generation New Orleanian. Driving with my mother down Esplanade Avenue always turns into a tour of family houses and history: “Maman and Grandad lived for a while in what is now the Hare Krishna house, after Uncle Buddy was born. Papite first lived on Bayou St. John and then later on North Galvez …. The Sarrats were on Bell Street.” A universe of Louisiana French culture within a few short blocks. My roots are deep, but I didn’t move to New Orleans until I was 10 years old: my father’s teaching work had carried us to West Virginia; my mother’s homesickness pulled us right back to the Crescent City. And early on, I became both an observer and participant in New Orleans culture. During raucous family Christmas gatherings in Gentilly, I placed tape recorders under the couch to capture all the delicious local stories (duck hunting tales, Mardi Gras adventures, stories about my Grandfather’s job at Maison Blanche), nicknames (Skeets, Fliva, Minneo, Swiss Cheese, Plib), and debates (everything from trouble with Edwin Edwards to theological throw downs with priests and nuns), all of it so idiosyncratic and specific to this place.

I attended Catholic grammar school in Harahan, Catholic high school at St. Mary’s Dominican, then it was off to Jackson, Mississippi, to Millsaps College. Like many writers, I couldn’t fully see New Orleans culture until I left. When I went to grad school for playwriting, I was the only writer in my class from the South, and one of the only writers who had not attended an Ivy League school. I was intimidated. It took me a while to understand what an incredible college I had attended—unknown to these (sorry) Yankees—and how unique my upbringing had been, steeped in Catholicism, tradition, and fiercely local ways of eating, talking, and celebrating. None of my early work is set in New Orleans. But I was writing from my roots, and I believe this gave me the intuition to create a unique, tightly woven culture for each play. One of my first professionally produced plays, Anna Bella Eema, features three women sitting in chairs facing the audience, speaking and singing a ghost story. It’s an epic mother-daughter tale filled with talking animals, little girls conjured out of the mud, and an epic police chase seen through the eyes of a mother who believes she’s turned into a werewolf. Couldn’t be farther from a Tennessee Williams play, right?

And yet somehow I believe he gave me permission. To be a Southern writer. To be a sensual writer. To be an extravagant, lyrical writer. And to be fiercely female.

I remember reading Streetcar at Millsaps College in Bob Padgett’s class on tragedy. The instructions: Analyze the play according to the rules of Greek tragedy, with Blanche as the tragic hero. What is her hamartia, her fatal flaw? How does this lead to the climax of her story, and then the catharsis, or resolution/revelation? I remember being confused for a moment. Analyze Blanche as the tragic hero? But wasn’t Stanley the main character? These were the questions of a 19-year-old Lisa, studying under the influence of biases and assumptions about who gets to be the main character in a play. As I read the play, I began to see how much Williams allows Blanche to own the stage, own the play. Even after she is defeated by her rival, it’s Blanche who demands our attention to the bitter end when she delivers the line that arguably defines the play, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” I am certain this was my first experience of a female character as a larger-than-life protagonist. Here was a woman acting with incredible, nearly unstoppable intent.

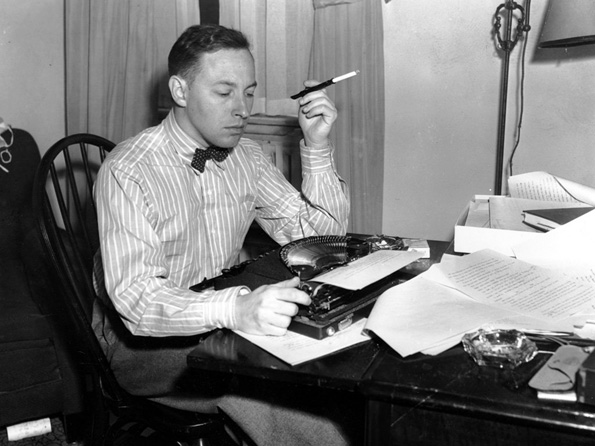

Tennessee William seated at his typewriter, 1945. Courtesy the Library of Congress.

For my play Detroit, which has been produced across the U.S., including recently at Southern Rep Theater here in New Orleans, I knew I wanted to write about two very different heterosexual couples living next to each other. One could be considered “stable,” one “unstable.” I knew the two couples needed each other and, in some ways, wanted to BE each other. The scenes are set in the couple’s backyards, and the play culminates in a raucous barbecue / dance party / bacchanal. Early in previews at Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago, some audience members talked to me about how the women were the center of the play: each of them have monologues that are like arias, laying bare their deepest needs and sorrows. Here’s Mary, one half of the “stable” couple, in Scene 2 of Detroit. It’s the middle of the night. She’s met Sharon, her counterpart in the “unstable” couple, the day before. Now she is in her bathrobe, banging on Sharon’s door, crying for help. Sharon opens the door in her T-shirt and underwear. This scene is abridged from the original:

SHARON

Mary what’s—

(Does Mary fall into Sharon’s arms? Anytime Mary curses she says that word kind of under her breath.)

MARY

Its just… I don’t know how to help him. I’m at the frayed edge of my wits. He gets to be home all day, and I don’t get home until 6:45 because of the fucking traffic on 694. And he’s been home all day and I get home and he’s already on his first drink. He says it’s his first drink anyway. And he’s cooked dinner, which is of course very sweet, but then I say something about how his green beans taste different than my green beans. You know, like “oh these taste different,” just like that. Not saying anything bad, but he drops his fork and I know he’s offended and then it starts….And so I ask, “How was it today? Did you bring the files to Kinkos?” And he’s like, “Oh shit, no I forgot. Oh well, I’ll do it tomorrow.” And I say, “You know you can do it on their website through the file uploader. Its’ super easy.” And he says, “Yes. YES! I know.” And I say, “well you know that book you bought for $65.00 said you’ve got to be hard on yourself about keeping to a schedule. Because Joe Blow down the street is also probably laid off and also probably about to set up his dream business where you get to sit home all day and tell other people how to clean up the fucking financial wasteland of their day to day existence. And if Joe Blow gets his portfolio together before you do then Joe Blow gets the clients, not you.” And he says, “Joe Blow can suck my nutsack”

(Pause for a moment. That word is like a bad taste in her mouth.)

And I say, “Oh that’s a winning attitude.”….

(Does Mary grab Sharon’s shoulders?)

I want to live in a tent in the woods. With one pot and one pan and an old-fashioned aluminum mess kit with its own mesh bag. I want my hair to smell like the smoke from yesterday’s fire, when I cooked my fish and my little white potatoes. I want to dry out my underwear on a warm rock and feel the cold water rushing around my ankles, my feet pressing into the tiny stone bed that holds up the stream. Silver guppies nosing their heads into my calves…

(Quiet for a moment. We hear suburban wind, maybe a car passing on another street. Maybe some teenagers laughing, maybe some kid in the house across the street listen to music in their room.)

SHARON

Were you a Girl Scout?

MARY

Yes.

SHARON

I thought so.

(Mary leans over into the bushes, she doesn’t get up, she just leans over, and pukes. And pukes. And sits back up.)

MARY

Oh god, my head. I think I need some water.

All I can say is, thanks, Tennessee, for building my instinct to let women characters fearlessly inhabit a play, in all of their contradictions, taking up all the space they need.

When I started writing my latest play, Airline Highway, I thought: the hotel itself is a main character. I’m going to describe it carefully at the top of the play, like Tennessee Williams so carefully describes the worlds of his plays. Detroit ends in a fiery dance party. Airline ends in an even bigger meltdown at dawn, as a rag tag group of friends who work in the New Orleans service industry celebrate the life of their mother figure, a dying burlesque legend named Miss Ruby. The play is set in the parking lot of a crumbling motel nestled in the outskirts of the city, on the road that gives the play its name. The Hummingbird Hotel is a hellhole to some, a castle to others, and I needed to make these contradictions live and breathe throughout the play. Tennessee provided inspiration.

“…the room must evoke some ghosts; it is gently and poetically haunted by a relationship that must have involved a tenderness which was uncommon.” —From Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

“The apartment faces an alley way and is entered by a fire-escape, a structure whose name is a touch of accidental poetic truth, for all of these huge buildings are always burning with the slow and implacable fires of human desperation.” —From Glass Menagerie

“Wayne shuffles into his office. For a moment, the courtyard of The Hummingbird Hotel stands alone, settling just a half a hair into the wet earth below.” —From Airline Highway, end of Act One

Of course my stage direction is child’s play compared to Tennessee’s. But one must strive, right? The physical world of a great play IS mystery, IS action, IS poetry, IS history, IS danger, IS conflict. Blanche knows exactly how to show Stanley who’s boss: occupy the one bathroom in his house for hours, fill it with perfume, and take all the hot water for a long bath. Bam! Stanley loses his swagger and his cool.

In Airline Highway, the motel is a refuge for a group of friends who feel they’ve been evicted from their biological families and mainstream culture. During the play, they wonder if there is still a place for them in New Orleans. A Costco is being built across the street. The owners of the hotel are coming around more, taking measurements, showing the place to strangers. The party that rages for Miss Ruby takes over the parking lot, the office, and every balcony. At one point, before they bring Miss Ruby out to honor her, a character named Tanya tries to rally her troops (this monologue is abridged from the original):

TANYA

That’s right baby you are at the HUMMING BIRD, and we may be a little rough around the edges but if there is one thing we know how to do, it is throw down a party.

(Bait Boy gives a “yip yip”!)

That’s right it’s Jazz Fest and our dear friend is sun setting and needs to be celebrated. Because people don’t celebrate enough in this life—they let things roll by unnoticed…

I mean how would this city SURVIVE without us? Who’s gonna serve those belligerent frat boys drinks?

Who’s gonna make sure the whole slutty bachelorette party gets up on stage for the booty dance?

Who’s gonna serve the half-drunk housewife from Charlotte “Sex on the Beach” out of a test tube you are holding in your cleavage?

Celebrate, you hear me?

‘Cause we had to go down a long strange road to be who we are, a road filled with construction and road kill and booby traps and scam artists and bad decisions masquerading as good decisions and bad luck masquerading as good luck and bad friends masquerading as good friends and treachery lurking around every corner, and you just stay on the road—

Looking for an exit, and when you realize there is no exit you get out and start walking—

You start walking and you keep walking along the edge of the highway with no idea of where you’re going or where you belong, until one morning the sun rises and you find yourself here. And there is no one else like us in the whole world.

(A moment, Tanya is winded, this rant has taken her someplace she did not expect. Everyone is looking at her.)

TANYA

Yes, we are.

I can only imagine Tennessee Williams, the man he was among fellow writers. But I can hear my version of Tennessee shouting a similar rallying cry—calling me to create worlds that speak the truth, however ragged it may be. And as I continue to write in my New Orleans home, two blocks from my parents, two blocks from my brother, niece, and nephew, and with aunts and uncles a few miles away, my job is to continue to observe this life and reflect its complexity. To use a Streetcar symbol, it’s my job to create the paper lantern for the light, and rip it off, mercilessly, when it’s time. I don’t know a world without Tennessee’s work. It’s shaped me, and I will always be, in some sense, an apprentice, working towards his particular poetry, a magic weave of place, character, and relentless desire.

—–

Lisa D’Amour is a playwright and co-artistic director of PearlDamour, an OBIE-award winning interdisciplinary performance company. Her play Detroit was a finalist for both the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and Susan Smith Blackburn Prize.