Fall 2017

The Tale of Deas and Poe

Artist Michael J. Deas envisions Edgar Allan Poe and his work

Published: September 7, 2017

Last Updated: September 17, 2018

Michael J. Deas is no stranger to the philatelic world. (For strangers to the philatelic world, philately is the collection, appreciation, and study of stamps.) Stamps featuring his artistic renderings include some of the most popular ever produced by the Postal Service. More than four hundred million of his 1995 Marilyn Monroe stamp were issued, placing it in the blockbuster category. The Marilyn stamp was the first issued in the Postal Service’s Legends of Hollywood series; it was celebrated with public events around the country. His 1996 James Dean stamp enjoyed similar success. Prior to his proposal for the Poe stamp, Deas served as artist for the Tennessee Williams, Katherine Anne Porter, Cary Grant, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, Humphrey Bogart, Audrey Hepburn, Bette Davis, and Thomas Wolfe stamps, to name a few. In all, he has painted images for twenty-one US Postage Stamps.

Michael Deas was also no stranger to the scholarly world as it pertained to the study of Edgar Allan Poe. The stories of Poe fascinated him as a young man. The first time Deas approached the subject of Poe in his own work was an etching executed as the frontispiece for a hand-lettered edition of Poe’s poem, “Ulalume,” when Deas was the tender age of nineteen. Deas became fascinated with images of the author—particularly with the lack of authentic images, and with the volume of fakes and misattributed images. As a result, Deas spent the next ten years researching the subject, culminating in the publication of The Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe by the University Press of Virginia in 1988. In this volume, Deas describes the history and provenance of the twelve known life portraits and daguerreotypes of Poe, as well as the apocryphal portraits, lost portraits, and copy daguerreotypes. It is widely considered the definitive volume on images of Poe. During the course of his research, he located a lost daguerreotype in the collection of Columbia University; he also located a forgotten miniature in the collection of the Huntington Library, one of only three confirmed portraits of the author painted from life.

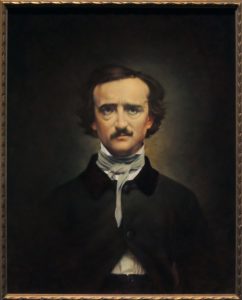

Although the Stamp Advisory Committee originally envisioned four stamps based on Poe, only one was ultimately released. Over the course of developing the final stamp, Deas designed and executed four tinted sketches based on four daguerreotypes and illustrations inspired by the author’s works. The version chosen for the 2009 stamp was based on the “Thompson” daguerreotype, taken by William A. Pratt in 1849. The stamp was designed under the direction of Carl T. Herman; the narrative based upon The Fall of the House of Usher was removed for the final painting. The preliminary study now hangs in the Poe Cottage in New York. The final painting was exhibited along with original manuscripts at the Morgan Library in New York in 2014; it is now held in a private British collection.

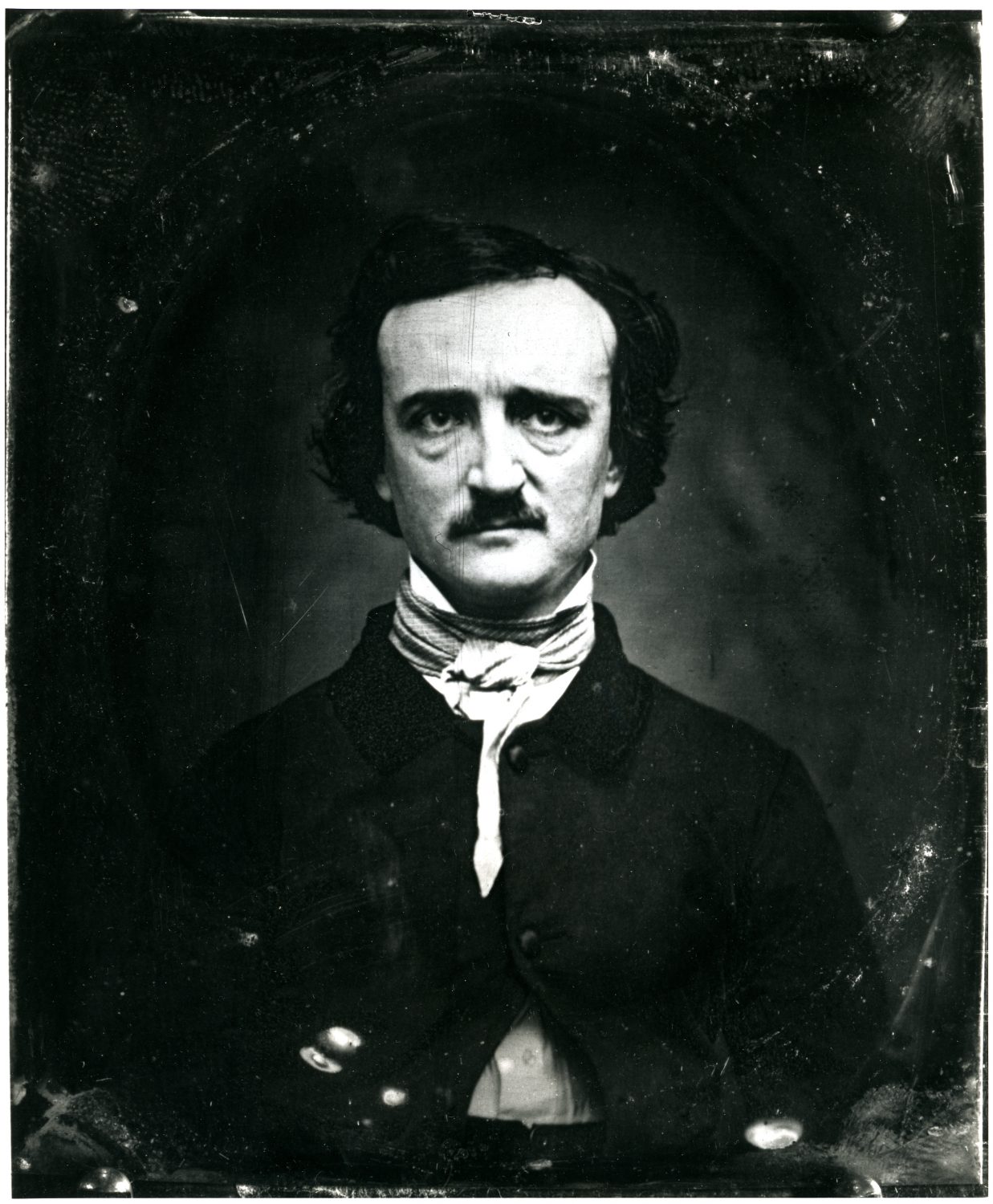

Ultima Thule daguerreotype

The second sketch to become a finished painting was based upon the “Annie” daguerreotype and illustrated with reference to The Tell-Tale Heart. After inquiring into purchasing Deas’ original of the second stamp design, only to discover it was unavailable, Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro commissioned the completion of the second sketch. Again, the narrative was removed from the final version. The “del Toro Poe” was exhibited—along with Deas’ portrait of H. P. Lovecraft—in Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2016.

The third and final sketch to be finished as a painting was based upon the most famous image of Poe, and inspired by his most famous work, “The Raven.” The “Ultima Thule” daguerreotype by Edwin Manchester was taken just four days after Poe had attempted suicide with an overdose of laudanum in 1848. It has become one of the most celebrated literary portraits of the nineteenth century. As the Ogden Museum prepared to mount a survey of Michael Deas’ work in 2012, it was clear to curator and artist alike that a portrait of Poe was essential to the narrative. With the two previous portraits unavailable for the exhibition, Deas agreed to finish the third portrait. On October 1, 2012, the third portrait of Poe was unveiled to the public, sharing space with other iconic images from Deas’ career—including the “torch lady” painting used as a logo for Columbia Pictures for more than twenty-five years—as well as the edition of “Ulalume” that started it all. Thanks to the generosity of collectors Michael Wilkinson and Roger Ogden, the “Ogden Poe” is now part of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art’s permanent collection.

Michael Deas has, for the most part, transitioned from illustration commissions into a series of highly original masterworks drawn from his own mind, rather than historical research. Recently I asked the artist, “After all the research, reading, and scrutiny, what does Poe mean to you now?”

He confessed that he doesn’t spend much time with great author anymore. “You feel as if you get to really know a person after that level of research, though,” he explained. “He became more than the stereotype of the tortured artist to me. I see him as brilliant and flawed and very human.”

Deas still feels that there is one piece of unfinished business with Poe, though: the missing “McKee” daguerreotype from before 1843. “The daguerreotype was sold at auction in New York in 1905 for a mere twenty-one dollars—not a particularly low price in an era when daguerreotypes were considered only slightly more valuable than a postcard—and has not been seen since. It could be in someone’s attic, and they are completely unaware,” he muses. While Deas dreams of finding the final missing Poe, I can’t help but think of his fourth and final sketch of Poe, the one based upon the “Whitman” daguerreotype and inspired by “Annabel Lee.” Perhaps there will be yet another chapter in the story of Deas and Poe.