United for Justice

How two Black-owned newspapers launched Louisiana’s civil rights struggle

Published: September 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

The Historic New Orleans Collection

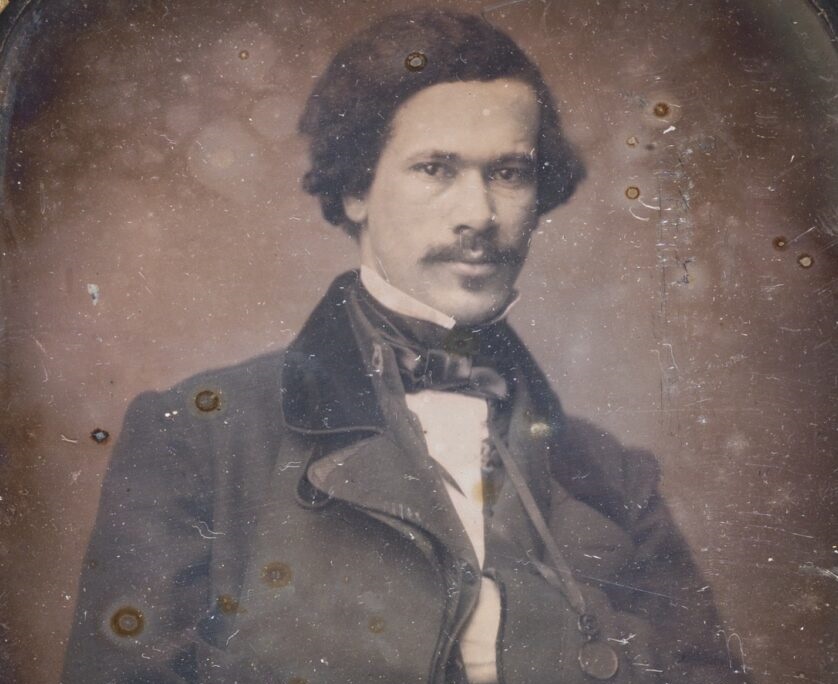

Louis Charles Roudanez in 1857.

Pandemonium gripped New Orleans when Union forces captured the city in the spring of 1862. With cracks in the Confederacy splayed wide open, Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez, Jean Baptiste Roudanez, Paul Trévigne, and other free Black leaders launched L’Union, a French-language tri-weekly journal, on September 27, 1862. The newspaper brandished words like a rapier. “Men of my blood! shake off the contempt with which your oppressors, in their ignorant pride, have ceaselessly covered you,” exclaimed Nelson Fouché in the December 6, 1862, issue. “March, live, it is your right . . . it is your duty.” Just a few months before, such words were inconceivable—indeed illegal—in the heart of America’s largest slave trading city. Now, among those of African descent, a cautious optimism arose. “We opened our hearts to hope,” said Arnold Bertonneau in the April 28, 1864, issue of L’Union. A free man of color and captain in the Louisiana Native Guard unit that had quickly joined the Union Army, Bertonneau observed, “It seemed to us that we were given a new life, and we began to make some beautiful dreams.”

As the leading voice of les gens de couleur libres—the free people of color—the journal advocated for the enslaved but emphasized the interests of their French-speaking constituency. L’Union believed free men of color deserved citizenship, including the right to vote, by virtue of “their past conduct and by the degree of civilization which they have reached.” An editorial in the newspaper declared that “All those who . . . have lived in New Orleans long enough to be familiar with the [free] colored population of this city are in favor of endowing this population with the elective franchise.”

By the fall of 1863, L’Union had become increasingly frustrated with the mounting opposition to their citizenship claims. In response, the newspaper promoted assemblies at Economy Hall that resulted in a petition, signed by almost one thousand men, boldly demanding the electoral franchise for all of African descent, “whether born slave or free.” On March 12, 1864, Jean Baptiste Roudanez and Arnold Bertonneau presented the document to President Lincoln at the White House. The meeting influenced the President, who quickly asked Louisiana Governor Michael Hahn to consider the matter for “the very intelligent, and those who have fought gallantly.” Hahn ignored Lincoln’s recommendation, and the push for equal rights stalled.

It was becoming increasingly problematic for L’Union to navigate the disheartening political and racial currents. As slavery gradually disappeared in Louisiana, so too did the distinctions between free people of color and the emancipated. An Americanized racial construct of Black and white was rapidly solidifying, and conservative forces that equated citizenship with whiteness were gaining ground. If a new racial democracy was to be won, a majority coalition of free Blacks and the 330,000 formerly enslaved Louisianans would be crucial. With the tide turning against them, it was time for a new battle plan.

L’Union printed its last edition on July 19, 1864. Just two days later, Dr. Roudanez unleashed a new and decidedly more radical newspaper. The New Orleans Tribune (la Tribune de la Nouvelle Orléans) defiantly vowed to “spare no means” to promote equality for all men of African descent: “We demand, like all other citizens . . . the right to come and go; the right to vote; the right to public instruction; the right to hold public office; the right to be judged, treated and governed according to the common law.” The Tribune agenda included redistribution of plantation land to the emancipated, streetcar desegregation, the creation of integrated public schools, impartial access to public facilities, equitable legislative representation, and full citizenship rights.

“It seemed to us that we were given a new life, and we began to make some beautiful dreams.”

In a strategic shift, the Tribune walked away from old divisions between free people of color and the enslaved, stating, “They [the enslaved] are of us, and we love them as we do ourselves. We are the organ of the oppressed, without distinction.” The newspaper desired “for all colored men what we claim for ourselves.” It envisioned a new alliance with the freedmen, embracing the importance of being “united in a common thought: the actual liberation from social and political bondage.”

To reach a much wider audience, each issue of the Tribune appeared in English and French. The English section reported on the desperate plight of the freed, local injustices, the mistreatment of the Black military, Union policies of leniency toward pardoned Confederates, Reconstruction politics, and much more. The French section devoted greater attention to international issues, philosophy, history, and the arts. It featured serialized novels and published early, often political, poetry by men of African descent.

By 1866, the Tribune was printing three thousand issues a day. The newspaper was read throughout Louisiana and the Gulf South and gained a broad following in the Union Army. Copies were distributed in the halls of Congress, where Senator Charles Sumner and other Radical Republicans viewed the journal with great interest. Many Northern newspapers reprinted Tribune articles, significantly expanding its reach. Stories from correspondents and writers throughout the world, including Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi, appeared within its pages, and the paper circulated among European intellectuals. It was highly regarded by Northern abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, who wrote to Tribune publisher Jean Baptiste Roudanez, “I see it and read it with very great pleasure. I am proud that a press so true and wise is devoted to the interests of liberty and equality.” The Tribune kept all these audiences apprised of the predicament facing Black Louisianans, bearing witness to their struggle as Reconstruction unfolded.

With the Tribune promoting unity and suffrage for all men of African descent, alarmed state legislators attempted to drive a wedge between free men of color and the freedmen. In late 1864, a so-called “quadroon bill” proposed limiting voting rights to those who were one-quarter Black or less. The newspaper vehemently rejected the divide-and-conquer tactic: “There may be among our population a few aristocrats of light skin, but they are in the minority. The majority of us know by experience that caste distinctions can only create bitterness and weakness . . . our first duty is to demand for all colored men what we claim for ourselves.”

These militant journalists could have more easily attained citizenship rights for free men of color. But they were profoundly influenced by the Haitian, French, and American Revolutions. Dr. Roudanez, who had “been before the barricades” in 1848 while studying medicine in revolutionary Paris, returned to New Orleans with “liberté! egalité! fraternité!” still ringing in his ears. He believed America was on the cusp of a fundamental transformation. “Yet a day will come when, by the logical march of progress . . . all the nations will be fused into one brotherhood,” prophesied the paper. “The annihilation of the tyrants and oppressors will usher in that happy epoch for humanity.” Instilled with a liberation mindset, the newspaper envisioned “the permanent establishment of a new and truly republican system” with justice for all as its cornerstone. New Orleans had emerged as the epicenter of a freedom movement built on visionary ideals.

The Tribune grasped the poisonous absurdity of racial classification. “It is a well-known fact . . . that there are very few families . . . in the city of New Orleans whose blood is pure of all mixture,” stated the paper. “The status of ‘white’ was a civil or legal character, much more than a matter of fact.” At the same time, the editor maintained that race was all too real, regardless of self-identification, understanding from experience that all people of color, whether born free or enslaved, were subject to mistreatment at any time by anyone who thought, spoke, or acted as white. “We cannot forbear distinctions when they are perpetuated against us,” admonished the journal. “We are ready to have all lines obliterated, and to forget all about race and color. But as long as you remain partial . . . self-defense compels us to oppose class to class and distinction to distinction.”

The Tribune tirelessly confronted notions of Black inferiority, serving as a counter-narrative to an overwhelmingly prejudiced white press and public. “If there exists unfitness somewhere,” observed the paper, “it is with the white planter, who knew but one thing—slave driving—and to whom every other occupation and business is not only new and repulsive, but even beyond the reach of his comprehension and intelligence.”

Remarkably, the Tribune did much more than report the news. Fiery editorials ignited mass meetings and demonstrations. “It is not by remaining isolated that the oppressed people can obtain redress,” proclaimed the newspaper. “It is only by coming out in a phalanx, by marching on in a strong column, that we shall obtain our due.” The paper organized the Freedmen’s Aid Association as a Black land ownership alternative to the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency regulating plantation labor that the journal characterized as “a system of disguised slavery.” In early 1865, the Tribune was instrumental in the creation of a local branch of Frederick Douglass’s National Equal Rights League. That summer, a coalition of Black and white radicals orchestrated unsanctioned statewide elections to demonstrate the fervor with which men of color would vote. In a formidable exercise of citizenship rights, over nineteen thousand men of African descent unofficially cast ballots for delegates to an upcoming convention and for representatives to bring their concerns to Washington.

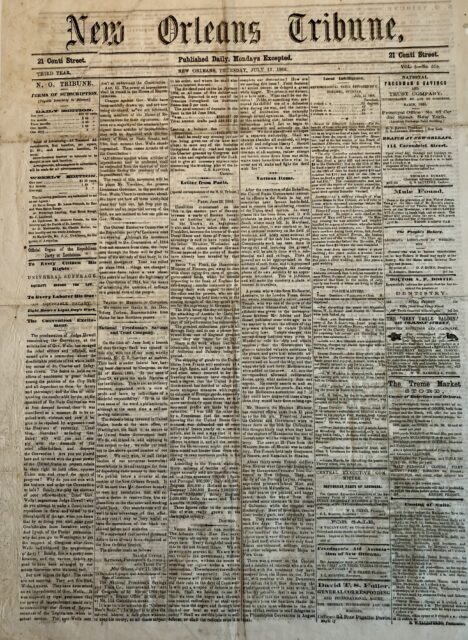

The July 12, 1866, issue of the Tribune contains a key editorial related to an upcoming constitutional convention convened by Black men and a few white radicals at the Mechanics’ Institute on July 30, 1866. Attendees were attacked by white supremacists in what became known as the Mechanics’s Institute Massacre. Mark Roudané.

In 1867, the Tribune’s voting rights campaign grew. Congress—suddenly controlled by the progressive wing of the Republican Party—wasted no time enacting Radical Reconstruction Acts that mandated new constitutions and guaranteed Black suffrage in the Southern states. “Many persons do not seem to have realized the change that has been brought about by the enfranchisement of the colored people,” reported the Tribune. “The fact of the men of African descent being admitted by law to full citizenship, entitles them to the same rights, privileges and immunities as every other class of citizens.” In September, over seventy-five thousand Black Louisianans voted for delegates to the upcoming state constitutional convention, this time legally. Fifty of the ninety-eight elected representatives were Black men born enslaved or free.

As the convention concluded, an election for state officials rapidly approached. The Tribune endorsed Black former military officer Francis Dumas for governor, but Henry Warmoth, a white carpetbagger deeply distrusted by Dr. Roudanez, was instead nominated to head the Republican ticket in the general election. Furious at a process he believed rigged, and unwilling to compromise, Roudanez bolted from the Republican Party. The move proved costly. Rebuked by the party, his newspaper suddenly found itself without institutional and financial support. Sadly, the Tribune ceased regular publication in early 1868.

The Tribune died, but its radical platform was not lost. The newspaper was instrumental in the creation of the 1868 Louisiana state constitution, arguably the most far-reaching charter in Reconstruction history. The constitutional convention delivered a groundbreaking blueprint for Louisiana’s future that included most of the civil rights and citizenship provisions the journal had campaigned for: universal manhood suffrage, integrated public schools, abolition of the Black code laws, guaranteed public rights, and racially proportional representation. Louisiana’s first mixed-race legislature was elected, and Black legislators and their allies would continue the Tribune’s fight until a fierce white backlash ended Reconstruction in 1877.

Even though the Tribune’s vision of freedom unraveled, its legacy endured in an ongoing protest tradition. In the 1890s, a second wave of dissent coalesced around the Crusader, a Black Republican newspaper founded by L. A. Martinet, resulting in a challenge to segregation in Louisiana that would lead to the historic Plessy v. Ferguson US Supreme Court case. That battle generated another cadre of twentieth-century civil rights activists who fought Jim Crow laws throughout the state and nation. And today, a new generation is still in the fight.

Many Americans, living in the despicable shadow of slavery and resurgent racism, would likely agree with the courageous stance of a newspaper that sparked a fire so long ago: “We are seeking to throw off a tremendous load which has been our inheritance for centuries. With us the burden is a reality and no abstraction.”

Mark Charles Roudané, a native of the Crescent City, is the author of The New Orleans Tribune: An Introduction to America’s First Black Daily Newspaper. He is the great-great grandson of Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez and has spent the last decade passionately researching his ancestor’s groundbreaking newspapers. Roudané’s work has appeared in numerous journals, including the South Atlantic Review and the Atlantic. He may be contacted at [email protected], www.facebook.com/roudanezhistory, or www.roudanez.com.

This article is part of Split Press: Democracy, Race, and Media in Black and White, a four-part multimedia series exploring the relationship between the media and African American and Afro-Creole experiences of citizenship and civil rights in Louisiana. Part of the Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative, Split Press is a project of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities made possible by a grant from the Federation of State Humanities Councils with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For additional Split Press coverage, stay tuned to 89.9 WWNO New Orleans and 89.3 WRKF Baton Rouge.