Spring 2023

Warning: This Article Could Be Banned

In Louisiana, like the rest of the country, attempts to ban books rise during times of cultural shifts that discomfort segments of society.

Published: December 8, 2022

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

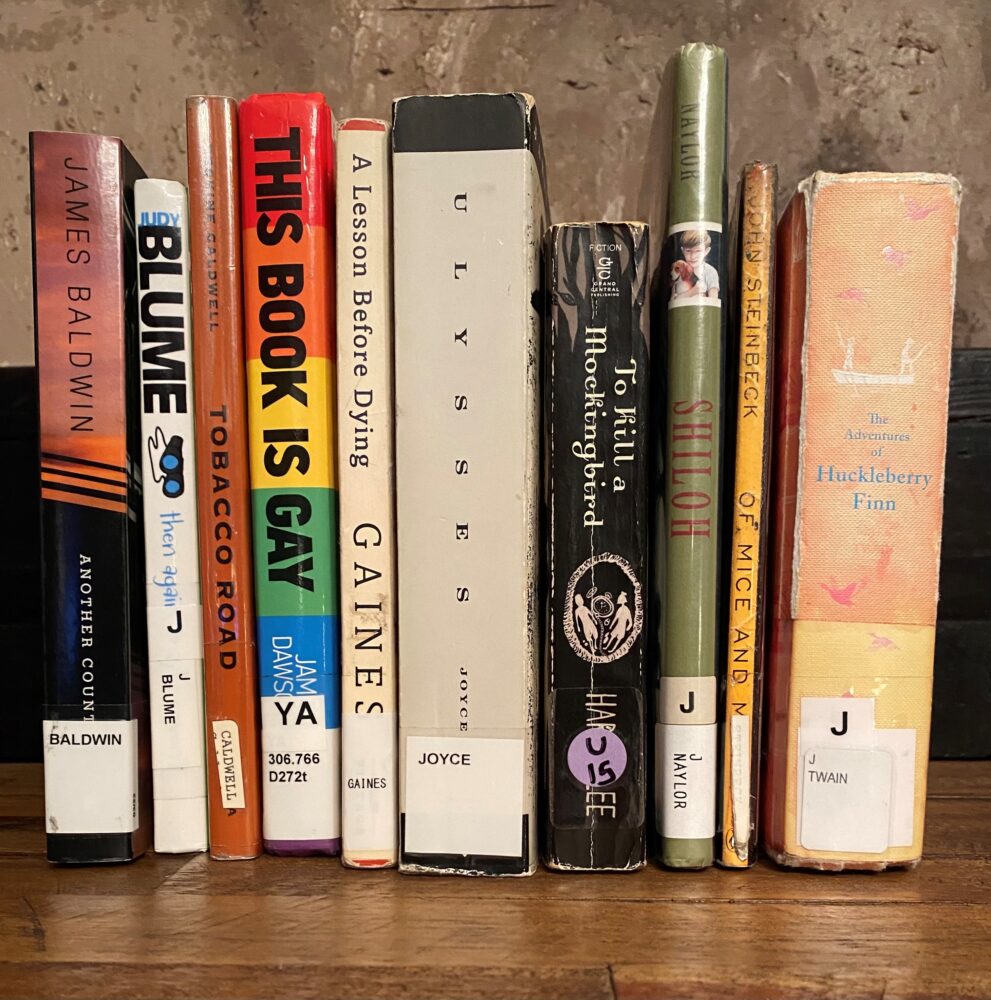

A rogue’s gallery of frequently challenged books.

Editors’ Note, 1/11/2023: In adapting this story for print publication, minor edits were made in order to reflect further book challenges and Danny Gillane’s decision to stay with the Lafayette Parish Library. The online text has been updated accordingly.

It didn’t take long for Debbie Coleman to convince the school librarian to destroy books she deemed offensive.She walked into Andrew Jackson High School on a February day in 1976 and headed straight to the library. Coleman knew just where to find it; she had graduated from the all-girls public school in Chalmette just two years prior. She met the librarian and began listing books she believed could corrupt the young female students, and then the two went to work.

“She just tore them up, tore all the pages out of them and threw them in the garbage,” Coleman told a New Orleans Times-Picayune reporter shortly after her literary sabotage.

Coleman’s strike on her alma mater’s library resembled other acts people have taken across Louisiana over the years to remove books from shelves or otherwise limit public access to them. Like efforts both before and after hers, Coleman’s was the work of one individual who believed that she acted for the public good and who was swayed by a small group of like-minded activists facing a world with changing cultural attitudes. Efforts to choke off access to books often come from people who find the works upsetting because they offer a view of the world that is different from their own.

Often, the most celebrated books inspire the most concern.

Those that have sometimes vanished from Louisiana bookshelves seem plucked from a college required reading list: A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest J. Gaines, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck. The list of American classics that have been challenged in the state—along with lesser-known but also beloved books—goes on and on.

On that day in Chalmette, by the time school officials discovered the wreckage and asked Coleman to leave, the trash can was lined with ripped and crumpled pages from works such as Ulysses by James Joyce, a target of censors in the United States since it was first serialized in an American journal in 1918; Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell, about white Georgia tenant farmers depicted as backward primitives; and Our Bodies, Ourselves, a collection of women’s writings about female health and sexuality.

Coleman told the reporter that there were other books on her hit list: dictionaries.

“Some have quite a few obscene words,” the young woman said.

Usually, those who would ban books face librarians determined to keep their shelves stocked with works that offer broad perspectives and represent a range of thought, even if the ideas presented are unwelcome, disagreeable, or otherwise make some readers uncomfortable. A library’s mission includes empowering all people with the right to choose for themselves what to read—or avoid. The Louisiana Library Association “denounces censorship of any kind, particularly in libraries,” it notes on its website, adding, “censorship always has been and always will be antithetical to librarianship.”

At Andrew Jackson, the school librarian complied with Coleman’s requests because of an unfortunate fluke of happenstance. The St. Bernard Parish Schools had a supervisor of materials whose role included overseeing the holdings of the district’s school libraries. His secretary was named Debbie. When Coleman announced herself by her first name, the librarian assumed the person before her with a mission to obliterate books was that Debbie, the secretary with the school board.

Instead, private citizen Debbie had snuck in her censorship moment. But it didn’t last long.

“We do not believe in the destruction of books,” Dr. Thomas Warner, assistant superintendent of schools, told the same Times Picayune reporter. He subsequently required Coleman to make an appointment for any further visits and use a formal complaint process—something almost all public and school libraries now have in place—should she have concerns about other books. Dictionaries remained on the shelves.

At the time of Coleman’s actions, the personal liberation and societal rebellion that had emerged during the 1960s had continued to transform the culture. Men grew long hair, women wore short skirts, and more of them openly engaged in premarital sex and abhorred the de facto racial segregation that carried on despite the laws passed years earlier to abolish it.

Evolving values in a changing world may have been the backdrop, but a nearby event was likely a more immediate influence. Just months before Coleman’s action, a group that dubbed itself the Concerned Citizens and Taxpayers for Decent School Books in Baton Rouge had lost their challenge of five books in the Tara High School library, which would have impacted all libraries in the East Baton Rouge Parish school system. Those works included the American Heritage Dictionary, Black Boy by Richard Wright, and The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers edited by Langston Hughes. The complaint contended that the books contained obscene, immoral, or unpatriotic content. All but one member of the seven-person review committee disagreed, voting to keep the books available in the schools. The lone vote in favor of the ban came from a member of the Concerned Citizens group. Babs Minhinnette, the group’s chairman, had helped Coleman create her list of targets at Andrew Jackson High.

Book bannings are a lagging indicator and a reaction to something that is already happening in society,” said Emily Knox, an associate professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the author of Book Banning in 21st-Century America.Challenges to books generally follow societal shifts in the country. For those who find evolving mores unsettling, an attack on books can be a balm. Knox explained the reasoning like this: I am upset about some new idea; I want to make sure my children don’t learn about it; the idea must be in books; we must avoid circulating those books.

Over the years, censorship efforts in Louisiana seem fueled by that smothering sensibility.

In 1937, New Orleans police seized and destroyed The Rise of American Civilization, a book by Charles and Mary Beard that suggests the Founding Fathers penned the constitution in part to protect their economic interests. Two other books were destroyed that year: Stubborn Roots, by Elma Godchaux, a novel about life on a Louisiana sugar plantation, and Green Margins, by E. P. O’Donnell, a novel set in the Louisiana Delta that features a pregnant and unmarried sixteen-year-old.

The Orleans Parish district attorney declared James Baldwin’s novel Another Country obscene in 1963. New Orleans Public Library branches responded by removing the book from public access, but the city’s Doubleday bookstore continued to sell copies—until police raided the store and destroyed them. A year of litigation returned the novel, about relationships that involve bisexuality and extramarital affairs, to library shelves.

In 1984, a St. Tammany Parish school superintendent pulled Edith Jackson by Rosa Guy and Then Again, Maybe I Won’t by Judy Blume off library shelves. A school board committee made up exclusively of central office supervisory staff agreed that the book’s “treatment of immorality and voyeurism do not provide for the growth of desirable attitudes.” The decision was later overruled by the school board.

A year later, the Caldwell Parish School Board considered removing the Newbery Medal–winning children’s novel Shiloh, about a boy and an abused dog, from the reading program at Grayson Elementary. A Caldwell Watchman newspaper article written about the decision reached the author, Phyllis Reynolds Naylor, and she wrote a letter to the newspaper and members of the school board. Children will not begin using foul language or kicking their pets just because a crude man in her novel does those things, she argued. “If this is the case, we must ban ‘Treasure Island’ because they might want to become pirates; ‘Huckleberry Finn’ because they might want to own slaves . . . and they surely should not read the Bible, which is loaded with murder and mayhem.” At the next month’s school board meeting, the board approved the continued use of the book.

In 2000 Plaquemines Parish Schools Superintendent Jim Hoyle rid the schools of To Kill a Mockingbird, whose 1961 Pulitzer Prize for fiction seemed not to matter. The movie based on the novel was also banned. The reason? Some parents complained that the book contained objectionable words. Still, Mockingbird eased back into use with teachers who had been hired after the original ban and were unaware of its existence. In 2013, the ban was reissued.

A new wave of book challenges has cropped up recently in libraries around the country. The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom found that the rate of book challenges begun in 2021 is outpacing previous decades.Pen America, a nonprofit organization that promotes free expression in the United States, reported last fall that it had found 2,532 instances of books being banned from July 2021 through June 2022. Most of the challenged books focus on LGBTQ issues or document the experiences of Black or BIPOC individuals.

“Race and gender identity are what’s on people’s minds right now,” Knox said.

That focus is evident in Louisiana. At press time, the Rapides Parish Library Board of Control will soon vote on changing its collection policy to exclude books referencing obscene or sexual content—including sexual orientation and gender identity. In St. Tammany Parish, more than seventy books, many with LGBTQ themes, have been removed from the shelves and placed behind the circulation desk pending formal review (ongoing at press time). They are the subject of challenges by citizens; given the volume, the board has extended its review timeframe from 45 to 120 days.

The Lafayette Public Library garnered national attention when public backlash in 2018 halted a planned Drag Queen Story Hour, in which drag performers would have read affirming children’s stories aloud. Eventually, the event was held in 2020 to a packed audience.

There is more than one way to diminish access to books. In 2021 the conservative-leaning library board rejected a grant that would have been used to buy books and host public discussions on the history of voting rights. (Disclosure: the grant was awarded by the Louisiana Endowment of the Humanities, publisher of 64 Parishes.)

Days after that board decision, the long-serving library director, Teresa Elberson, resigned. Her replacement, Danny Gillane, stepped into the role in February 2021. He also flirted with leaving. Gillane announced his decision to depart in early 2023—a decision he later reversed, hoping to oversee the building of a new library—after Robert Judge was elected to a second one-year term as president of the Library Board of Control in November. Judge has attempted to ban books and oust librarians from a committee that reviews patron objections to books.

A month before Judge was voted in, Gillane sat at a table in his office on the top floor of the Lafayette Parish Main Library taking questions from a reporter. Behind him, a giant peace sign dominated a floor-to-ceiling window, sending a cheering message to the outside world. Gillane wants peace and free access to books.

He explained that after he and members of the library board met with Michael Lunsford, executive director of Citizens for a New Louisiana, a conservative organization, he knew that book challenges were coming. Gillane made a preemptive strike, obliterating the teen non-fiction section and dispersing the books that had been there among the adult books. Though some people find such actions themselves a form of censorship, Gillane believed it could at least keep the books on the library shelves.

Furthermore, he dispersed the entire teen non-fiction collection instead of only the LGBTQ-focused books that appeared to be the target of would-be book censors.

“I was adamant I wasn’t going to single out one group and move books for just that audience. Let’s move them all,” he said.

“We have never banned a book at the Lafayette libraries,” Gillane said, but then added, “But don’t get me wrong. Someone will get a book removed from this collection at some point.”

Perhaps someone already has.

At the Main Library, in the social science section, which is tucked away in the very back row of books on the third floor, the only two works that faced official challenge weren’t on the shelf where they belonged, tucked between similar titles.

The electronic library search system showed they were available. Instead, This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson, call number 306.776, and The V Word by Amber Keyser, call number 306.7v, were nowhere to be found.

The librarian at the help desk peered into her computer when asked about the books’ locations.

“Assumed lost,” she said, after looking at her records for This Book Is Gay. She explained that occurs from time to time when a library patron checks out a book and never brings it back.

And The V Word?

Assumed lost.

Kerri Westenberg, a New Orleans writer, was the travel editor at the Star Tribune in Minneapolis for many years. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Real Simple, Bon Appetit, and other magazines.