What More Do You Need?

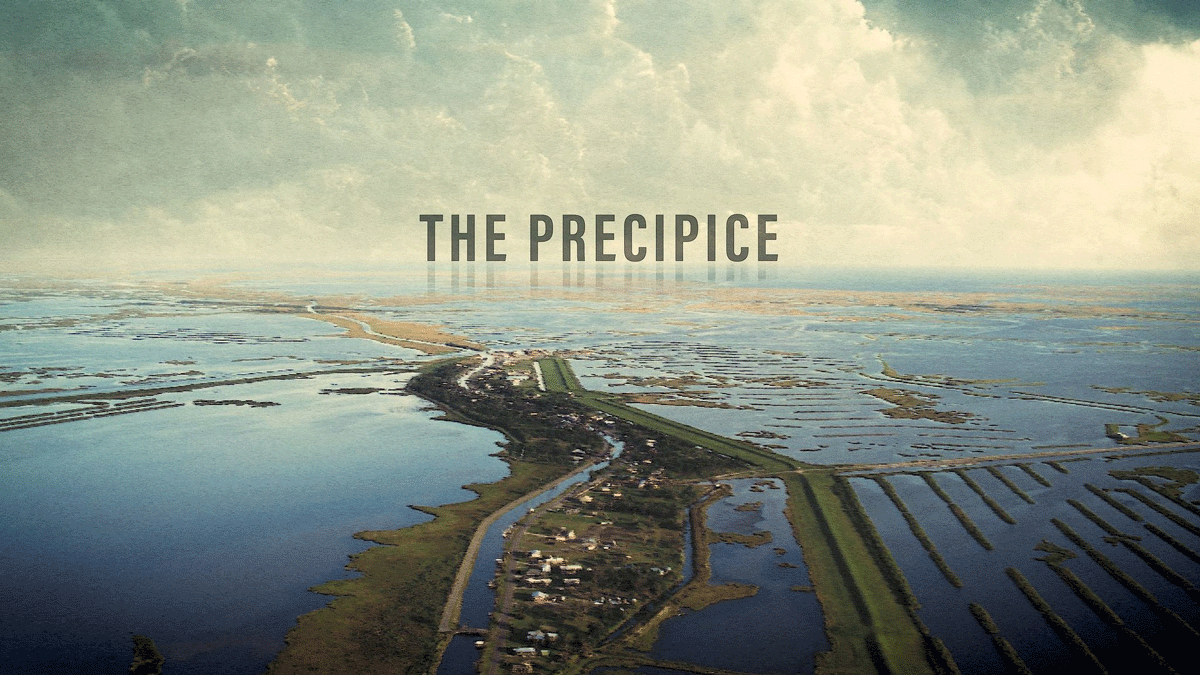

The Precipice, the 2024 Documentary Film of the Year, documents the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe’s fight for federal recognition

Published: June 1, 2024

Last Updated: September 1, 2024

Louisiana Public Broadcasting

Camp is in session around picnic tables on the concrete ground floor of an elevated home. Children weave willow baskets; they identify local medicinal plants; they chant back at their teacher: “Mon coeur est dans la terre de ma famille.”

My heart is in my family’s land.

Held each summer for local children ages eight to fourteen, Culture Camp is one initiative the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe of southeast Louisiana has taken in its fierce effort to keep language and traditions, including fishing, hunting, and farming, alive in its 850 members. The cultural rejuvenation is an undercurrent to the prevailing fight for an irrevocable claim on the ancestral land where the tribe’s children hope to remain, kicking back against state and federal laws and rapacious land developers who have, over the decades, dispossessed the tribe of their land.

The case is laid out in The Precipice, the debut production in Louisiana Public Broadcasting’s Louisiana Spotlight series. Directed by Ben Johnson, the documentary chronicles the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe’s ongoing pursuit of federal recognition. A dwindling population, eroding landscape, and regular visits from freakish hurricanes are all beasts the community is willing, even eager, to face down. But without recognition by the United States government, the Pointe-au-Chien cannot lobby for themselves effectively, whether for essential services like schools, healthcare, and libraries to remain in the community or for resources to be dispatched in the wake of a catastrophe.

Efforts to obtain recognition through the slow-moving Office of Federal Acknowledgment have officially been underway since the mid-1990s. In the film, tribe member and attorney Patty Ferguson-Bohnee remembers seeing a piece of legislation, introduced in 1996 but never enacted, that would have provided recognition for the United Houma Nation if they ceded all land claims, as well as that of shared progenitors, including the Pointe-au-Chien. “Maybe they don’t want us here because then it’ll just be a Sportsman’s Paradise to go fishing,” said Ferguson-Bohnee, “but this is our land, even if there’s not a lot of it left.”

The Pointe-au-Chien’s federal petition has been rejected at least once for a dearth of primary documents establishing the tribe in colonial history. Hope is renewed by an ease in regulations introduced by President Obama in 2015, promising quicker and more consistent decision-making. But the gathering of necessary paperwork—which must prove historic presence of the Pointe-au-Chien dating back to 1900 and descendants within the current tribe, among other requirements—is still arduous, likened to sorting out “tax receipts from Grandma.” In Ferguson-Bohnee’s view, the primary documents that tribes and researchers from the Office of Federal Acknowledgement currently use to establish Louisiana tribes in history have critical gaps in years, language, and perspective.

In the film, Tulane professor and historian Laura Kelley, who is assisting the Pointe-au-Chien with the petition, cites the complication of the Louisiana Purchase in connecting the land back to the Pointe-au-Chien, who descend from the Chitimacha among other tribes. “Napoleon doesn’t sell actual title to land,” Kelley explains. “What he does is sells the idea that you can now go into this land and try to claim it for your own. So they’re sending surveyors out in the 1830s, 1840s, to mark certain features but also [existing communities].” These descriptions can be inaccurate: “Oftentimes when you look in this part of Lafourche and Terrebonne, they call it the Trembling Prairie—trembling land—and with almost no waterways even noted.”

Livelihoods were more diverse than the fishing that dominates marshy Pointe-au-Chien today, where the abundance of saltwater supports seafood and little else. “It was very fertile,” says Ferguson-Bohnee in the film. “You could catch food to eat. You’d make your houses from the palmettos. . . . Your houses were on the ground. There wasn’t a great risk of flooding. There was fresh water, so people had big gardens. You were able to provide fresh water for your cattle. Everything you needed, you had available to you.”

If aerial footage of Louisiana’s dissolving coast no longer startles you, The Precipice puts the loss into the Pointe-au-Chien’s own terms, as Ferguson-Bohnee tours the bayous by boat with fellow tribe member Donald Dardar at the helm, conducting a survey of the tribe’s parcels for the camera. “That’s supposed to be ours,” she says, pointing at one patch of gusting reeds. “There’s Fala,” she says of another empty isle. As recently as the ’70s, community members gathered in Fala for a baby shower. “Fala n’est plus là.” It’s no longer there.

The Precipice catalogs historic and recent injustices done to the tribe while highlighting the parties within and alongside the community who aren’t giving up on the federal fight or the daily coastal life just yet, even after the devastation of Hurricane Ida and the recovery that limps along without federal resources. “Our parents didn’t go through storms like we go through,” says one tribe member in the months after Hurricane Ida. “And then our grandparents, when they were growing up, the land was still growing. Someone should be accountable for that, because the land has changed around us and made us more vulnerable. And we didn’t contribute to that.”

The Pointe-au-Chien’s contributions are focused on bolstering the tribe through education and community-building, keeping alive the old ways and making themselves better heard in the process. On a recent visit to the area, the French consulate was shocked to hear obsolete words alive and bobbing around in the Pointe-au-Chien dialect. “He said he hasn’t had a meeting like that in Louisiana,” said Ferguson-Bohnee, “the whole community speaking French and engaged in French.”

Lucie Monk Carter is a writer and photographer in Baton Rouge.

Restore the Mississippi River Delta is a coalition of Environmental Defense Fund, National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, and Pontchartrain Conservancy. Together, we are working to rebuild coastal Louisiana’s nationally-significant landscape to protect people, wildlife and jobs.

Restore the Mississippi River Delta is a coalition of Environmental Defense Fund, National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, and Pontchartrain Conservancy. Together, we are working to rebuild coastal Louisiana’s nationally-significant landscape to protect people, wildlife and jobs.