Winter 2025

The Wildest Show

The controversial chaos of the Angola Prison Rodeo

Published: December 1, 2025

Last Updated: January 29, 2026

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

During the Wild Horse Race portion of the Angola Prison Rodeo, convict cowboys attempt to ride a bucking bronc bareback.

Spanning 18,000 acres in West Feliciana Parish, the 124-year-old Louisiana State Penitentiary—colloquially known as Angola for its antebellum roots and the small employee community established inside its perimeters—houses roughly 4,500 criminally convicted men. It is also home to the last of the great prison spectaculars, a biannual romp-and-stomp rodeo overload in the heart of the largest maximum security prison in America.

Each year, thousands of curious newcomers, sports fans, shoppers, journalists, and adrenaline junkies from across the country and around the globe traverse the winding, twenty-mile stretch of state Route 66 from St. Francisville that leads to the penitentiary’s front gate and the Angola Prison Rodeo. From the breakneck entry of the Rough Riders drill team to the breath-catching intensity of the Guts & Glory finale, the show is chaotic, controversial, gratifying, and complex.

The rodeo started in the mid-1960s as evening recreation for a handful of prisoners who tended the livestock. Convict cowboys cordoned off a swath of flatland, brought out the ropes and spurs, the swayback field horses and back lot bulls, and ate a lot of dirt. Informal free-for-alls, staged for the amusement of incarcerated onlookers and prison supervisors, raised the eyebrows of interested movers and shakers. The shows were fun, different, and held dynamic potential.

From the breakneck entry of the Rough Riders drill team to the breath-catching intensity of the Guts & Glory finale, the show is chaotic, controversial, gratifying, and complex.

At that time, the prison was known for its violence. Local historian and author Anne Butler describes the 1960s penitentiary in Angola: Louisiana State Penitentiary—A Half-Century of Rage and Reform (1990) as “a brutal world of violence and intrigue, political abuse and racial turmoil.” One in ten prisoners suffered stab wounds, and many wore body armor fashioned from mail order catalogs while they slept at night. Prisoners were forced to navigate “cramped and unsanitary living conditions, slave-like working environments, inmate-guards, a lack of clean clothes and hot water, and an in-house judicial system based on violence.”

“Convict Poker,” which involves four inmates seated around a red card table when an agitated bull is released into the arena, is a crowd favorite at the Angola Prison Rodeo. Photo by Kevin Rabalais

Corrections officials may have viewed a prison rodeo as a distraction from these awful conditions, or even a transformative catalyst for prisoners who had few positive outlets in their lives. Similar productions in Texas and Oklahoma were huge successes. While the penitentiaries at Huntsville and McAlester were not country clubs, unlike Angola neither had been branded “the bloodiest prison in America” by the press.

The idea for an organized program caught fire and spread all the way to Baton Rouge, where the Louisiana legislature created the Angola Rodeo Commission in 1966. Shortly thereafter, Institutions Director Wingate White announced that the penitentiary would host a “field day and rodeo” in the fall. About 1,200 prisoners and 500 invited lawmakers, sheriffs, reporters, and other VIPs attended the groundbreaking exposition. According to The Angolite, the prison’s news magazine, the show “was not the success we had hoped it would be.” Rain forced the cancellation of several events, and “made viewing uncomfortable for some.”

The October 1967 rodeo opened to the public on a limited basis. Live action was broadcast over radio station WLUX Top Gun in Baton Rouge. “A small crowd” of spectators sat on apple crates and the hoods of their cars to watch the performances, because the grounds consisted of only the fenced-in arena.

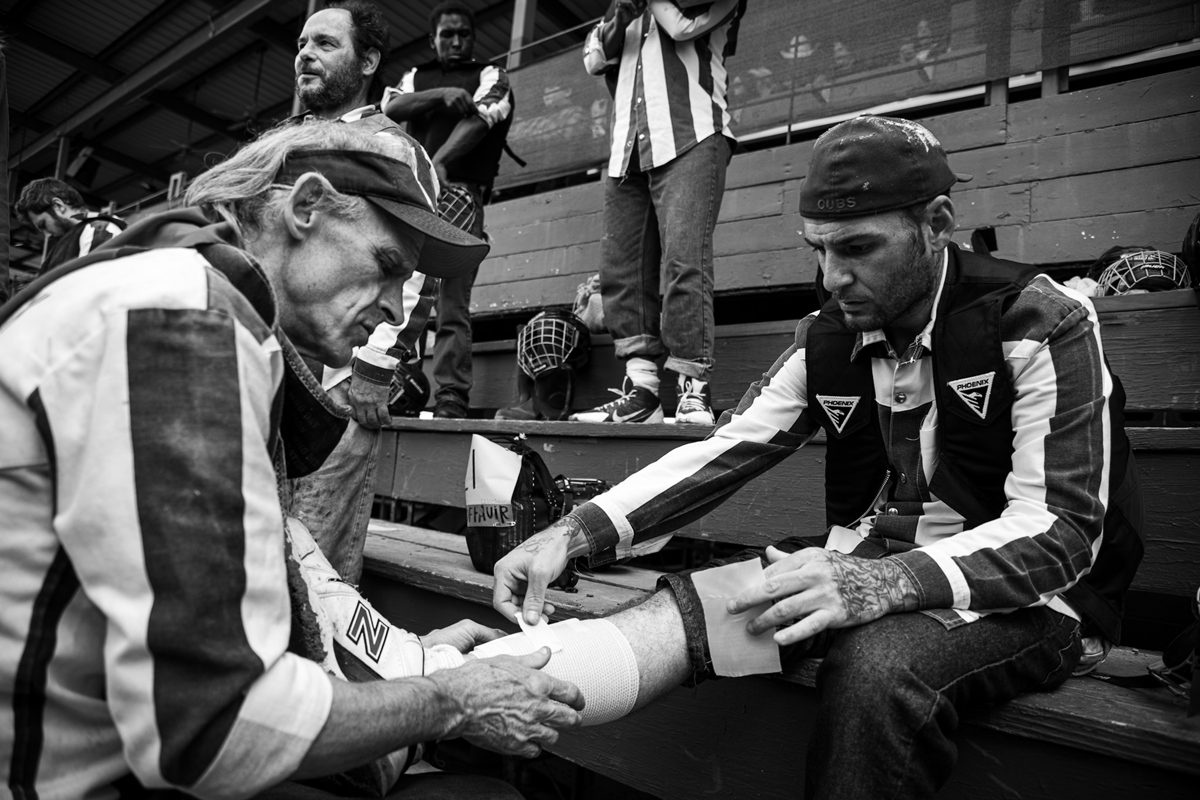

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

In the early history of the rodeo, two men—one a convict and the other a prison employee—warrant special note. Jack Favor was a retired professional rodeo performer, a four-time world champion steer wrangler and bulldogger who arrived at Angola in 1967 after being wrongfully convicted of murder in Bossier Parish. Before his conviction was overturned in 1974, “Cadillac Jack” immersed himself in the disjointed prison rodeo and transformed it into a professional operation that would attract upper-level entertainers and hordes of paying visitors.

Farming supervisor James “Boss Dick” Oliveaux had a flair for rodeo decorum and a manager’s penchant for detail. He was a man who got things done, managing the convict cowboys and livestock for twenty years. Former Warden Hilton Butler told The Angolite that in the late sixties he and Oliveaux “took a bunch of inmates to Alexandria,” where they spent the night “tearing down some donated bleachers and bringing them back to Angola.”

The donated bleachers were assembled to form a modest arena off the southeast corner of the Main Prison compound in 1968. Corrections Director Lt. General David Wade invited the public to attend the “Angola Rodeo” over the July 13 and 14 weekend. Admission fees were $2.50 for adults and $2.00 for children.

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

A section of the newly constructed arena collapsed during one of the shows in 1969. Eyewitnesses reported that fans were so captivated by the rodeo they didn’t bother to move off the fallen bleachers.

Seating capacity was expanded in 1970 to serve 5,216 spectators. The musical lineup that year included bluegrass king Lester Flatt and “The Singing Sheriff,” Faron Young. Since then, many stars have played the arena, from Johnny Cash and Charlie Daniels to the Neville Brothers and John Schneider.

By the time Governor Edwin Edwards opened the 1976 show, the rodeo had morphed into a major Louisiana attraction that routinely drew record-breaking crowds.

The rodeo continued to grow in popularity during the 1970s, adopting official Rodeo Cowboys Association rules—such as the eight-second rule for a successful bronc or bull ride—in 1972. By the time Governor Edwin Edwards opened the 1976 show, the rodeo had morphed into a major Louisiana attraction that routinely drew record-breaking crowds.

During the twenty-year tenure of Warden Burl Cain, the rodeo enjoyed a golden age. Cain inherited a prison culture in 1995 that was already shifting toward productive interests among inmates, as harsh sentencing laws and narrowed release avenues resulted in a prisoner population that had aged out of the criminal mentality. He directed rodeo proceeds toward chapel construction and other self-improvement programs throughout the penitentiary. Cain encouraged incarcerated craftsmen to behave so they could make money too, as long as they produced quality products and charged fair prices. He used the media and internet to advertise “The Wildest Show in the South,” and commissioned inmate artists to adorn the sides of penitentiary transport vehicles with colorful advertisements that drew the eye and piqued interest. The outreach worked. Fans poured into Angola.

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

Arena spectator capacity was increased in 1997 by 1,000 seats. Today’s modern stadium, completed by incarcerated builders in time for the 2000 rodeo and expanded in 2007, accommodates 10,500 fans. From its upper tiers can be seen the Main Prison East dormitory units and recreation yard, the industrial compound, the rolling Tunica Hills, and the earthen levee bridling the mighty Mississippi River.

Following a two-year pandemic hiatus during 2020 and 2021, the rodeo’s return in April 2022 under Warden Tim Hooper seemed more a lumbering administrative tradition than a vital resurrection. Faced with an aging population that affected participant viability, returning Warden Darrel Vannoy added a handful of professional bronc and bull riders to the event rosters in 2024 to spice up the action. To counter a marketing slump that witnessed a significant exodus of event sponsors and program advertisers, Vannoy recruited a former employee in 2025 to help reenergize the marketing strategy.

“Angola’s rodeo is the most ambitious effort of all,” writes Dennis Shere in Cain’s Redemption (2005), “to show society that in many respects inmates harbor the same desires to win respect and achieve success as anyone else.” Shere observed that the rodeo “allows many of the prison’s inmates to see that the barrier separating them from society is not impenetrable. Though they may never again live as free people, they can at least connect with the outside world a few times a year.”

Some convict cowboys ride for bragging rights, some for the prize money that varies from a few dollars for team events—like the comical Wild Horse Race that pits a trio of would-be saddle jockeys against a bucking bronc—to hundreds of dollars for Guts & Glory—a signature event in which the boldest cowboy attempts to snatch a chip from between the bull’s horns. Winners are recognized at an awards ceremony later in the year that comes with a fine meal and engraved, saucer-sized belt buckles.

Twenty-two-time Guts & Glory record-holder Marlon Brown said he might wear the buckle for a while and then “send it home to my mama like I do the rest of them. She keeps everything.” But he will not allow his mother to watch him perform. “I tell my brother, ‘Don’t bring Mama. I don’t want to give her a heart attack.’ The way I act [in the arena]? She’s not ready for that.”

Brown admitted he has taken some knocks during the show. A bull once headbutted him and split open his jaw, but he was back the next day. “I feel like, if you don’t break my leg, you ain’t did nothing. If he can’t stop me from coming, I’m gonna keep coming at him. I gotta get paid. That’s all that matters.”

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

Rodeo is a dangerous sport. Despite the crash helmets and padded vests, men are carted out of the arena with injuries ranging from deep muscle bruises to broken bones. Participants are required to sign hold-harmless agreements. They know the risks. They get hurt, they go to the hospital, the show goes on.

“You rodeo because you love it,” said former Angola Prison Rodeo stock contractor Dan Klein, nodding toward a line of contestants pairing up for a head count. “This is their glory. They do it because they love it.”

Participants are required to sign hold-harmless agreements. They know the risks. They get hurt, they go to the hospital, the show goes on.

Not everyone is enamored with the rodeo. The penitentiary rises from the tainted earth of slave-owning cotton and sugarcane plantations and has, in the eyes of some, retained a semblance of master–slave mentality into the present. Many reformists say that a disproportionate number of incarcerated Black people, forced labor policies, and the perilous, exploitative rodeo confirm the inhuman treatment of one of society’s most vulnerable subsets: prisoners.

Black Louisianans make up about one-third of the state’s population, but roughly 80 percent of Angola’s incarcerated residents. “The power dynamics at play are obvious and shaped by White Southern traditions,” writes Capital B reporter Adam Mahoney in a 2024 exposé, “that ignore the violent realities behind the spectacle.”

Mahoney spoke with Tony Grimes, a former prisoner who objected to the huge profits—nearly a half million dollars for each rodeo—the prison earned by exploiting, as he saw it, mostly Black participants for the enjoyment of mostly white spectators. But when Grimes tried to organize a boycott, he quickly discovered that the inmates who sign up for the show were not willing to protest “the only event that allowed virtually unfettered connections to the outside world and a chance to make money.” In this respect, the rodeo serves the prison’s interests as a behavior management tool.

Photo by Kevin Rabalais

Retired criminal justice professor Burk Foster has attended the rodeo for more than forty years. “I get the criticisms of it,” he said, “but what I appreciate most about the rodeo—and why I think many friends, family, and strangers keep coming back—is the openness of the day. Visitors have hours to speak directly to prisoners if they wish as they walk around the grounds.

“Many visitors who have attended the rodeo with me have said the experience was much more meaningful than they expected,” Foster added. “They might have come to see the animals and be entertained, but it’s the people they remember.”

As Lori Martin and her colleagues wrote in “Racism, Rodeos, and the Misery Industries of Louisiana” (Journal of Pan African Studies, November 2014), while prisoners are keenly aware of the racialized undertones and their own hazardous exploitation for cheap public entertainment, for rodeo participants the costs are outweighed by the benefits: favor from the warden and staff; interaction with the free world, and especially the women visitors and close family; entertainment, experience, challenge, and recognition; and the chance to make money and savor a taste of some kind of normalcy, such as it is.

Almost six decades ago, the Angola Prison Rodeo welcomed the general public for the first time. The show epitomizes a number of things, from manufactured self-worth to the commodification of social pariahs. Whatever its value to Louisiana culture and to human decency, the show still brings in the crowds, pads the local economy, and showcases many prisoners who will never be closer to freedom than an eight-second ride.

John Corley is the associate editor of The Angolite, the news magazine of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. His work has also appeared in The Atlantic, The Historic New Orleans Collection, Zócalo Public Square, and other publications.