Magazine

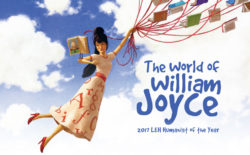

The World of William Joyce

From Shreveport to the Oscars and back again

Published: March 1, 2017

Last Updated: May 2, 2019

From William Joyce’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2012)

— Brian Boyles

Growing Up in Shreveport

I think that my parents had been so poor that their whole goal after the Great Depression and World War II was “Our kids are never going to have the sort of deprived upbringing that we had. We want them to find something to do that they love.” I think that’s awesome and amazing.

They were baffled that both my sisters and I, and all my cousins, were artistically inclined from day one. The idea of the arts as a venue on which focus your life? We would have been better off if we’d said we wanted to be from another planet. In some ways, it seemed like we were. But my parents and aunts and uncles were incredibly supportive. My cousin Johnny went to Juilliard. That was a bright beacon for me as a kid. Here’s this bigger-than-life character who goes to New York and studies opera and piano and acting, and comes back bringing his friends from Greenwich Village, putting on plays. My grandparents lived a few blocks from where I grew up. I remember helping my cousin read for Pinter plays. I was around ten. Bugs Bunny in the morning, Pinter in the afternoon.

Growing up in Shreveport, there was a symphony, an opera, a ballet, some very good art museums, and a thriving theater community. There were all these people who loved and supported the arts. It doesn’t happen often, but I’ve seen this in a number of funny little mid-sized cities. There’s enough determination on the part of a handful of people who think the arts are important, that they make them important to the fabric of that city. Shreveport was lucky in that regard. And it still is.

The Raven logo designed by Joyce during his freshman year in high school.

On the Influential Indulgence of Teachers and the Great Raven Scandal

I went to a little private school outside of town called the Agnew Town and Country Day School, run by this cool woman named Mrs. Agnew. There was a drawing that I did in kindergarten that got singled out because I had done all these things that five-year-olds don’t usually do. I’d put roots on the trees and individual blades of grass. It had real detail going on, and even a sense of perspective. From the time I was five people were going, “Whoa, this is unusual.”

Later on, I started taking private art lessons from this wonderful art teacher, Lee Wheelis. She took me under her wing and showed me every medium. “For six weeks, we’re going to draw with pen and ink. For six weeks, we’re going to draw with pencil. For six weeks, we’re going to draw with pastels. For six weeks, we’re going to do watercolors.” She made me do these things. You can’t underestimate the power of that kind of thing when you’re a kid, and the effect it has on you.

I went to C. E. Byrd High School where there was a wonderful teacher, Maredia Bowdon. She was a journalism teacher and ran the school newspaper. She understood the inner wildness of teenagers. Our newspaper was called The High Life. Years later, I went to one of my reunions and my wife Elizabeth came with me. Elizabeth began leafing through our newspaper and she says, “It’s like reading The New Yorker.” I was doing movie reviews, illustrations, and photography, and my pals were writing humor pieces and fiery editorials. It didn’t dawn on me until then what a rarefied thing we were able to indulge in.

Freshman year in high school, I was bored. We were reading Poe in freshman English, and that ignited a lot of things in my head. I took a couple of my friends aside and said, “I’ve got this idea. We’re going to make a sticker that says ‘The Raven,’ and get a bunch of them printed up, and stick them everywhere, and see what happens.” I had ten thousand of these black circular stickers, with white gothic print that said “The Raven,” and a crummy little silhouette of a raven. We’d stick them on lockers, or go to somebody’s house at night and cover their entire front door. Put them on all the cars in the teachers’ parking lot. We would leave a burnt-edged note that said, “The raven has struck.” The next day everyone would say, “The raven struck my house last night. What does this mean?” This went on for like four months.

Joyce’s drawing of children’s literature professor Coleen Salley.

I started getting more brazen. I went to the principal’s office and put one on the seat of his chair, and one right inside his desk. The day before Christmas break, the principal offered a five-hundred-dollar reward to anyone supplying information leading to the arrest and conviction of persons defacing the school in the name of The Raven. There are certain phrases that you hear once, but they burn into your memory forever, especially if they’re directed at your possible imprisonment.

My dad told me I should turn myself in. When we got back from Christmas, I was called to the office. Every scoundrel in school was there, all the usual suspects. They called me in first. I sat down with the principal and the vice-principal. The principal said, “Okay, what is this?”

“It seemed like a fun idea,” I said.

“Wait, really? You’re not some terrorist organization?”

“No,” I said, “it’s just to give people something to talk about. And I like Edgar Allan Poe.”

The principal sat there and thought about this for a second, and instead of doing anything damaging like calling the police, he said, “You will be allowed back in the school if you clean off every one of those stickers.” Which I did after school for weeks.

The principal’s name was B. L. “Buddy” Shaw. When I graduated from high school, Dr. Shaw gave me my diploma and he said, “So long, Raven.” Years later, he became a state representative and then a state senator, and in both of those houses of government, he proclaimed a “William Joyce Day” in Louisiana. Twice I appeared at the state capital, and both times he told that story of the Raven on the floor of the legislature. What kind of state does that, except Louisiana?

New York and the Golden Age of Publishing

I’d been sending stuff up to New York publishers since my freshman year [at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where Joyce studied film and journalism]. I had about 150 rejection letters, which was pretty depressing. The mother of a girl I was dating knew some guy who knew a man named Christopher Cerf in New York. His father was Bennett Cerf, who founded Random House. Chris helped start the National Lampoon. He knew everybody in publishing. He saw some of my stuff and said, “Look, I never help anybody out, but come to New York and I’ll get you a bunch of interviews, because I think your work is really good.” I went to New York, and the first interview I had was with Harper & Row, and they gave me a job on the spot. My publishing career began, much to my complete relief and surprise.

It was an apprenticeship. I was working with people there, some of whom had been in publishing since the 1940s, and again, it was the same kind of thing that happened when I was a kid. These grown-ups said, “I think this kid’s got something.”

My dad would pay for me to go to New York, where these old established editors and promotions people would take me out to these swank publishing watering holes. They still had the three-martini lunch back then. I just learned and soaked it up, sometimes with some of the people I’d read about, and the legends that I wanted to emulate. I’d stay at the Algonquin Hotel, because I’d read all that stuff about the Algonquin Round Table, and I worshipped those writers. The publishing people would say, “Bill, it’s kind of a cliché, the Algonquin is a shadow of its heyday.” I’m like, “I don’t give a shit. I’m at the Algonquin, sitting where Scott Fitzgerald and the Marx Brothers used to sit.”

There’s a heady, intoxicating atmosphere up there that can overtake you and reduce you. I knew I’d become a need-to-please hack if I stayed. I also felt a real cultural tie to home. I understood how to navigate the weirdness of home better than the weirdness of New York.

The World of William Joyce Scrapbook; William Joyce; Published by HarperCollins (1997)

Falling in Love

Elizabeth was dating my best friend, and I thought that he was nuts. I asked, “Who is this girl?” Then I got to know her, and I thought she was awesome. He was kind of a scoundrel and was treating her badly. I asked her out on a date. Then he asked me to take her out on a pity date, because he was going to break a date with her so he could go to a debutante party with this other girl.

I’m told him, “I kind of already asked her out, so it’s kind of moot.” He got mad at me, but we’re still good friends.

Elizabeth and I fell in love that night, bam. And she’s been in every book I’ve done.

Parenthood and Mythmaking

A lot of the stories I came up with were about something that was going on with my kids, or something that was going on with me because of them. “Rise of the Guardians” and “Santa Calls” came about because my daughter Mary Katherine asked me one day at breakfast, “Do Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny know each other?” Very matter-of-fact, just kind of like out of the blue. She was around five or six, and my son Jack was three.

I went, “Yeah,” then I had to back it up. I realized there’s no solid mythology to these icons of childhood. That seemed strange to me. We have all these icons, but we have exasperatingly vague ideas about them and how they do what they do, or even what they do or who they are. It crystallized for me in that moment. “Of course they all know each other. They work together. This is a big deal. There’s a bad guy. There’s got to be a bad guy, and that’s the bogeyman.” It all just fell into place.

It was always something, some kind of catalyst, usually a story I told to make my kids’ daily existence more interesting.

Morris Lessmore, Hurricane Katrina, and The Mardi Gras Cover

Bill Morris was one of the grand old gentlemen of Harper & Row and was one of my mentors there. He was a legend, a dapper gentleman, very dry wit, diminutive, and classy. I found out he didn’t have very long to live. I flew up to see him, and on the way, I wrote “Morris Lessmore” on the plane, making a play on his name, Bill Morris. It just poured out.

I got to see him, and there he was in an apartment, almost no furniture, ninety-nine percent books, hardly any place to sit. I told him the story. I was afraid he might not like it, because he was so dry witted, but he was touched by it. He died about three days later.

But I couldn’t get myself to finish the story. Then Katrina hit. Two days later, we had an emergency meeting of the Shreveport Regional Arts Council. Many of the people from the Arts Council of New Orleans had evacuated to Shreveport. Pam Atchison, executive director of SRAC, and Sandi Kallenberg pulled the meeting together. Sandi said, “We need to document what’s happened, because people will need to know this. People will need to remember this.” Within five minutes, we had the basic idea.

Within a week, maybe two, those two ladies had approval for us to take photographers and oral historians into the different shelters.

It was one of the most important things I think I’ve done. I find the older I get, that ninety percent of the time I’m responding to something that’s emotionally in my life. The reverence and the tenderness that people working in the shelters showed towards the people in the shelters, how protective and kind they were, kind in a way that helped everybody keep their dignity—I felt like I was seeing greatness. The stories and images we recorded, stories of what happened to them during and after the storm, were very powerful. Just being asked, “What happened?” seemed to help ground these people, and bring them back from hopelessness. It stuck with me that everyone’s story matters. And this all blended into the book and film The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.

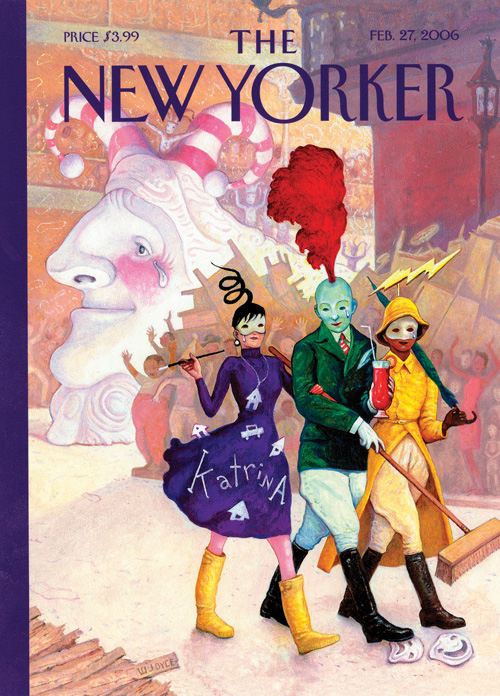

The cover that wasn’t: Joyce’s Katrina Rita Gras was bumped from The New Yorker, and later ended up as the cover of the spring 2016 issue of Louisiana Cultural Vistas.

I was in New Orleans in 2006, the first Mardi Gras after Katrina. My wife and I were members of the Krewe of Coleen. Coleen Salley was about five feet tall, maybe four-eleven, and maybe just as round. She cussed like a sailor, drank like nobody’s business, and taught children’s literature at the University of New Orleans forever. She was a legend in children’s literature and much loved throughout the entire industry, a proud and profane deity. Coleen began to push my career very, very hard, and we became great friends.

Her Mardi Gras parade began on Chartres Street in the French Quarter. The Krewe of Coleen all wore colanders on their heads and as many beads as could be found, and they wheeled her around in a shopping cart, festooned with beer cans, feathers, beads, through the French Quarter, usually howling drunk. Everybody in the Quarter knew and loved her. We would stop the shopping cart and chant, “Hail, Coleen, Queen Coleen. All hail Coleen, Queen Coleen! What a bitch!” She had this large, mechanical hand that would flip the bird at everybody. It was a perfectly Mardi Gras thing to see a jovial, drunk old lady in a shopping cart surrounded by hundreds of worshipers singing ribald songs.

This was right after the New Yorker had bumped my Katrina cover for a parody of Dick Cheney shooting his hunting buddy. They had promised me, “We will not bump it, guarantee you it’s going to run.” But they did. They said that New Orleans had been amply covered. I found that an insulting and miserable thing to say. So I put out my own press release about why the Katrina Mardi Gras cover had not run. Our state was hurting, and I was mad. The release went viral, and there I was preparing for Mardi Gras, helping Coleen into her shopping cart, and somehow David Remnick, the New Yorker editor, is on the phone telling me to shut my mouth. He said, “I’m hoping that you’re not trying to stir this thing up to some self-aggrandizement thing, and you won’t be releasing any more emails.”

I said, “Dude, I just wanted the people of New Orleans to know what happened. I’m never going to illustrate for you guys ever again at this point anyway. I’m just going to catch some beads now.” They gave me the rights, so I could make prints of it to raise money for our displaced artists. We raised a hundred thousand dollars, which we put into the Katrina Project. [Note: The piece was eventually published as the cover of the spring 2006 issue of Louisiana Cultural Vistas.]

During the parade, an ABC news crew sees Coleen and asks her what’s on her mind. She says, “That stuck-up son of a bitch at the New Yorker magazine!” Then the Times-Picayune and other papers picked up the story. The great irony of it all was that people in New Orleans still weren’t getting their mail, so they wouldn’t have got the New Yorker anyway. The only way they would even know about the cover was for it to get bumped. Everything had to go wrong for it to get right.

From William Joyce’s The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs (Laura Geringer Books, 1996).

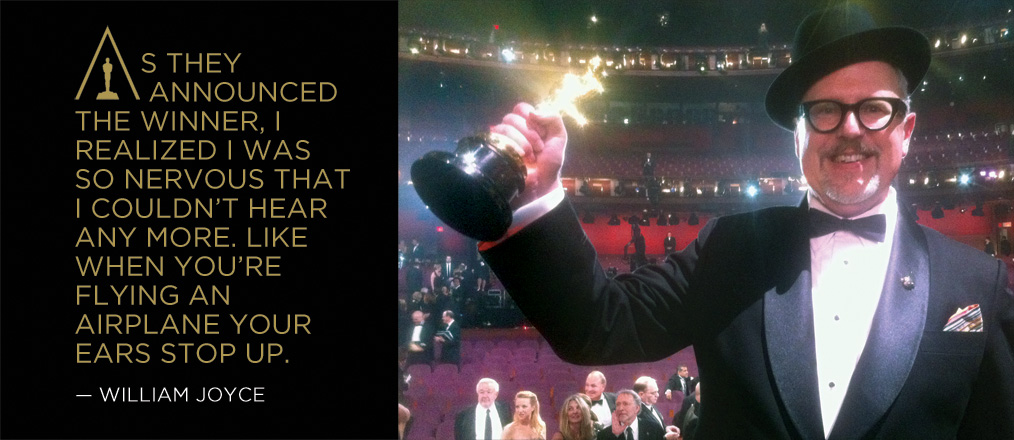

The 2012 Oscar for Best Animated Short Film Goes to…

The nominees are announced at 8:00 a.m., but there’s so much traffic, their website is crashing. We’re all at the Moonbot Studios, and finally the site comes up on the big screen. I’m staring at it, and I’m so nervous that I can’t read. I’m just staring at these letters and unable to make heads or tails of it for those few moments. Then everybody starts screaming in a happy way. I can read again, and there was Morris Lessmore. I think you could hear us screaming in Los Angeles.

Every day after that, we did interviews, several a day. One of the weirdest ones was Vogue Magazine. The reporter asks us, with a totally straight face, “Who will you be wearing at the Oscars?” Before I could think of any smartass answer, my partner Brandon Oldenburg said, “Dickies,” which was his smartass joke, and not true. Dickies makes overalls and work clothes. The lady from Vogue wrote it down: “Dickies of Fort Worth.”

The next day the president of Dickies calls us. “We’d love to make your tuxedos,” he says. “The only thing is, you have to use Dickies fabrics.” They sent a tailor to Shreveport from Chicago. He asks if want a shawl collar or a peaked collar, double-breasted or single-breasted. We had to pick our fabrics. We came close to getting camouflage tuxedos, but instead we did chose what they call “danger orange” for our pocket squares, jacket lining, and piping. It’s the orange they use for the traffic cones. That got us coverage from Isaac Mizrahi and Joan Rivers.

We had decided that we are going to have fun, because we may never get this chance again. At the Oscars lunch, we sit with George Clooney at the nominees lunch, boozing it up and having so much fun with him. We talk to Martin Scorsese, we talk to Spielberg, we talk to Meryl Streep. That’s when I realize that the whole Oscar thing is the movie industry saying, “Nice job.” It’s an extremely kind and generous thing in a town that’s not known for its kindness and generosity.

If you’re nominated, or if you’re a head of a studio or a major star, you’re down on the floor during the awards show. It’s a really long show and we were third from last for the evening. As they announced the winner, I realized I was so nervous that I couldn’t hear any more. Like when you’re flying in an airplane and your ears stop up.

On the screen in the theater, they list the nominated films by showing shots from each film. Suddenly I see the image of my wife as the woman in Morris Lessmore, flying through the air. My wife had ALS and was not able to move at all. We had tried desperately to get her to the Oscars but there wasn’t any way to do it. She ended up being there, if only on the screen and animated.

I regained my hearing. As they pull open the envelope, the place gets as quiet as a tomb. And I hear the girl from the movie Bridesmaids read, “The Fantastic . . .” My brain exploded. I felt like I was no longer a solid object. I was a gas. I was a joy gas, and as such I drifted down the carpet up to the podium.

I had our speech in my hat in case we messed up, and I said the first line of it. I looked down and there is George Clooney sitting right next to Sandra Bullock. He leans over to her, and I hear him in a stage whisper say, “Those are those short film guys, they’re pretty funny. But what’s inside their suits?” The glow from our danger-orange Dickies was illuminating our white shirts. Brandon heard him too, and we both forgot our speech. So we just babbled. I don’t know what came out. All I know is I said something about swamp rats in Louisiana, but everybody told us we gave one of the best speeches of the night.

Everybody has moments in their life, whether they’re in the movie business or not, where they have practiced their Oscar acceptance speech. I’ve loved the Oscars since I was a little kid. Then I actually win an Oscar and George Clooney makes me forget my speech.

We get home and there are people waiting at the airport to cheer us. A week later they have a ticker-tape parade in downtown Shreveport, the first ticker-tape parade since 1945, since the end of World War II. We had our own Moonbot Mardi Gras float, and Dickies was nice enough to make black coveralls for all the Moonbot crew. My wife Elizabeth was in her wheelchair, watching from the balcony of the Robinson Film Center. The mayor gave us the keys to the city and the crowd sang “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” And for that moment, it was like we were in the movies that we loved so much. Life became exactly like that, a Frank Capra movie set in Louisiana. It was a remarkable moment.