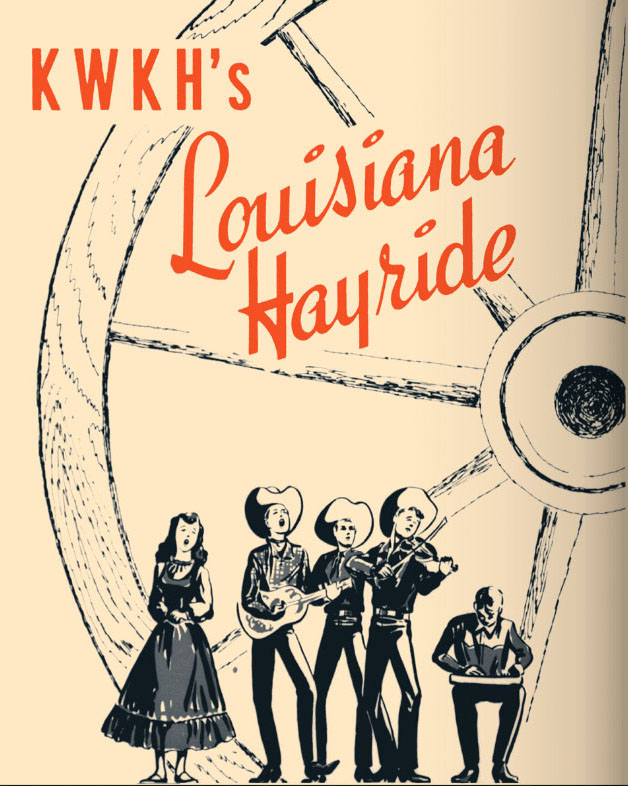

10 Fascinating Facts about the Louisiana Hayride

Shreveport's popular radio show helped further the careers of relative unknowns like Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley

Published: December 11, 2015

Last Updated: December 13, 2018

Against a painted backdrop of a farm scene, and facing enthusiastic blue-collar crowds eager to forget their workaday lives on Saturday nights, Hank Williams, Faron Young, Johnny Cash, Slim Whitman, Kitty Wells, Webb Pierce, Jim Reeves, Johnny Horton and Elvis Presley were among the relative unknowns who became famous in the spotlight of Shreveport’s Municipal Memorial Auditorium. Presented here are ten little-known facts about the heyday of this history-making hoedown of the airwaves.

The show’s name had been the title of a 1941 book by Harnett Thomas Kane, Louisiana Hayride: The American Rehearsal for Dictatorship, a critical examination of Huey Long’s autocratic rise to power as governor and U.S. senator and the cabal that seized his mantle after Long’s assassination in 1935. It was also the name of a song in the 1932 Broadway musical Flying Colors. Show manager Horace Logan decided upon Louisiana Hayride because “I wanted something that would promote country music—and then localize it.” Just prior to the opening broadcast in 1948, the Bailes Brothers and Red Sovine came up with an introductory song: “Come along, come along. The sun is shining bright, the moon is shining bright. We’re gonna have a Louisiana Hayride tonight.” Decades after the show closed, the Louisiana Hayride name and trademark became the subject of protracted copyright lawsuit between the Williams Partnership, a group that gained legal title to the registered name in 1992 as collateral from a loan default, and Margaret (Lewis) Warwick, a former Hayride performer who formed a revival group known as the “Louisiana Hayride Band” that same year. In 2009 a federal court ruled that Warwick owned rights to the name.

According to longtime manager Horace Logan, the Hayride averaged about 3,300 ticket sales per night (60-cent admission for adults and 30-cents for children) and frequently reached maximum capacity of 3,800 — particularly on dates when a young crooner named Elvis Presley was scheduled to swing on the microphone. The show was a major tourist draw, filling lodging and dining establishments on weekends when country music fans drove into Shreveport from the surrounding Ark-La-Tex region and far beyond. The city offered the Hayride use of the Municipal Auditorium for a mere $75 every Saturday night of the year with the exception of five weekends when the talent showcase was forced to tour other cities across the South, including the nearby towns of Monroe and Ruston, and farther afield in Houston, Oklahoma City, Little Rock and Corpus Christi. Shreveport’s hotel and restaurant owners would complain about a lack of customers when the Hayride went on the road. “If we had had to depend upon attendance from the city of Shreveport, it would have died after the first three or four weeks, and that’s true of any show,” said Logan in a 1976 interview. “Financially it was an excellent thing for the city and the city was aware of that. That’s the reason they gave us such concessions on the use of the building and so on down the line …”

In 1949 Horace Logan asked songwriters Red Sovine and Tillman Franks to compose a commercial jingle for the breakfast condiment, expecting turnaround within a few weeks. The duo brainstormed for ten minutes and came up with these humorous lyrics: “When I die just bury me deep with a bucket of Johnnie Fair at my head and my feet, and put a cold biscuit in each of my hands and I’ll sop my way to the promised land.” The syrup company also put forth $5000 for a 15-minute morning program on KWKH that regularly featured live performances by up-and-coming Alabama-born singer Hank Williams, who dubbed himself the “Ol’ Syrup Sopper.” These highly popular solo vocal-guitar broadcasts were recorded in 1949 on acetate and put into storage. Discovered six years later by a station producer, they were sold to Chess Records, who, in turn, sold them to MGM where they were issued as singles in 1955, more than two years after Williams’ untimely death at age 29. Williams died in the back seat of a car from heart failure, brought on by a combination of alcohol, morphine and chloral hydrate, while traveling through West Virginia to a show scheduled in Canton, Ohio.

On December 15, 1956, in an effort to settle frenzied crowds that were demanding an encore from the nineteen-year-old singing sensation, the Hayride’s emcee announced: “All right, all right, Elvis has left the building. I’ve told you absolutely straight up to this point. You know that. He has left the building. He left the stage and went out the back with the policemen and he is now gone from the building.” Presley, a former truck driver from Memphis barely out of high school, had made a few hit recordings at Sun Studios. He was invited to perform at the Hayride on October 16, 1954—a few weeks after he had flopped at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville. The Municipal Auditorium held the largest audience Elvis had ever faced and reports indicate he fell flat on his rendition of the African American blues song “That’s All Right Mama.” By the latter half of the show Presley, who billed himself as the “Hillbilly Cat,” had become more at ease and the house had shifted to a younger crowd. A second try at lyrics that read “Well, that’s all right now mama / That’s all right with you / That’s all right now mama, just anyway you do …” electrified the audience. Elvis drew capacity crowds thereafter and was signed to a one-year contract at the Hayride. Vernon and Gladys Presley had to travel from Memphis to witness the contract since their son was underage.

Southern Maid Donuts would offer a Hayride Special to patrons following the show’s Saturday night sign-off.

On November 6, 1954, Presley sang about the time of day when Shreveport’s Southern Maid Donuts shop would draw hungry sweet-tooths:

You can get them piping hot after 4 p.m.,

you can get them piping hot,

Southern Maid Donuts hit the spot,

you can get them piping hot after 4 p.m.

As a teenager with a voracious appetite, Elvis was known to make frequent visits to the bakery’s location at 2700 Greenwood Road, where a large neon sign would light up with words HOT, HOT, HOT to indicate when the confections were fresh from the deep fryers. Other performers who sang this short ditty on the Hayride stage included Minnie Pearl, Johnny Horton and Johnny Cash. The Johnny Cash version was released on the Best of the Louisiana Hayride Volume 4 CD in 2000 by Music Mill Entertainment.

Nashville’s WSM radio station began broadcasting lineups of “hillbilly bands” in 1925 on a live show called The WSM Barn Dance. The program earned a new vernacular title by way of an ad-lib remark from announcer George Hay when he faced the difficult task of segueing from a feed of classical arias from New York to the rustic tunes of rural Tennessee. In a mocking tone and with a thick Southern drawl, Hay told listeners, “For the past hour, we have been listening to music taken largely from grand opera. From now on, we will present the grand ole opry.” As it grew in prominence, the Opry typically only cast talent that had already recorded albums and established themselves with radio airplay. The Louisiana Hayride, on the other hand, became known as the “Cradle of the Stars” for its willingness to present and nurture less-established artists. Many performers who got their first break at the Hayride moved on to Nashville, which outpaced Shreveport as a base for national recording studios. Hank Denny, manager of the Grand Ole Opry, called the Louisiana Hayride the “Grand Ole Opry farm club.” Likewise, Horace Logan referred to the Opry as “the Tennessee branch of the Louisiana Hayride.” Traditionalists at the Opry originally banned drums and the electric guitar while the less conservative Hayride embraced them, making the Municipal Auditorium a laboratory for the early sounds of rockabilly and rock ‘n’ roll. The Opry was also a tightly scripted production, even down to the cornpone jokes, while the Hayride was improvisational. “There was no rehearsal, everybody just showed up,” said Bob Sullivan, former sound engineer.

Steve Grunhart, president of but the the Shreveport branch of the Federation of Musicians allowed for a few nonmembers to get their start on the Hayride, working without a card from 30 to 60 days, before he would them to pay dues on installments. Between 75 to 100 musicians would appear on stage on an average Saturday night for the four-hour production. The union pay scale per show was $18 for a bandleader and $12 for his or her band members. If a band consisted of five or more members, the featured artist would be bumped up in pay to $24. This was far less compensation than a typical Saturday-night gig at a honky tonk, but Hayride performers gained from the show’s exposure, which in turn led to recording contracts and more nightclub bookings.

Hank Williams Jr. was born on May 26, 1949. He was three years old when his father died unexpectedly from heart failure. courtesy of HankWilliams.com.

Williams and his wife Audrey moved to Shreveport after the singer had proven himself to be a sober and reliable radio performer at WSFA in Montgomery, Alabama. The Williamses had divorced once due to Hank’s bouts with alcohol abuse, but they arrived in northwest Louisiana reconciled and hoping for a fresh start in July 1948. “He rode into Shreveport with everything he owned on top of an old Chrysler,” recalled Horace Logan. “He had springs and a mattress and everything.” The couple welcomed a son, Hank Williams, Jr., ten months after their relocation. Hank Sr. nicknamed the child “Bocephus,” after the puppet of comedy ventriloquist Rod Brasfield, a regular on the Grand Ole Opry. Hank Jr. went on to a musical career of his own beginning at age eight when he would appear on stage to sing his late father’s songs. At age 15 he made his recording debut with “Long Gone Lonesome Blues,” one of his Hank Sr.’s biggest hits. In the 1970s Hank Jr. shed his confining impersonator role and emerged as a country music superstar in his own right. With his signature scraggly beard (grown to hide facial scars from a near-fatal accident), long hair, sunglasses and cowboy hat, he maintains a busy concert schedule in his late 60s. Hank Jr.’s material includes “All My Rowdy Friends Are Coming Over Tonight,” a party anthem that was used as the introduction for the ABC network’s Monday Night Football.

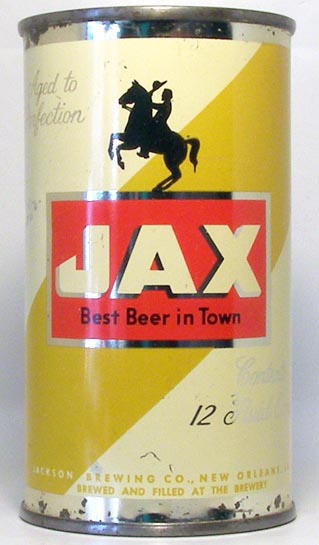

On occasions when the Municipal Auditorium was booked on Saturdays for other events, the cast and crew would travel to other locations for broadcasts, including once to Louisiana Tech University. After setting up an outdoor stage on the football field, torrential rain forced the show into the college’s field house. Jax Beer sponsored the first portion of the show, but not long into the segment the university chancellor stormed into the building. According to the recollections of KWKH sound engineer Bob Sullivan, the chancellor exclaimed, “You are advertising beer. This is a Christian school and I won’t have it! Shut it down now or I will have everything you have hooked up yanked out!” Horace Logan stalled the irate administrator long enough for the Hayride to proceed into a segment sponsored by Purina Feeds, ending the crisis. The signature beer of Red River Brewing Company in Shreveport is a wheat ale with a hint of rye and American hops under the trademark name Hay Ryed.

Reunion shows of former Louisiana Hayride musicians have been held in Shreveport in the decades following 1960, including a short-lived dinner theater that operated in Bossier City in the 1970s and ’80s, owned by David Kent. In April 2015 a ceremony to launch a revival of the show was attended by the mayors of Shreveport, Bossier City and Baton Rouge, Lieutenant Governor Jay Dardenne and a few former performers. Actor Billy Bob Thornton, in town to perform with his band the Boxmasters, spoke at the event. “We don’t want this stuff to disappear. This is a sacred building,” Thorton said. “We kind of got a chill coming in here, to tell you the truth.” A Louisiana Hayride Museum featuring a Hall of Fame has also been in discussion.