Henry Howard

Henry Howard was an important Louisiana architect of the nineteenth century.

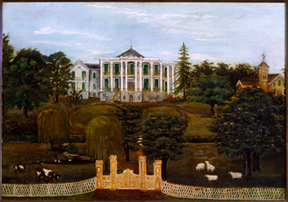

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Nottoway Plantation. Howard, Henry (Architect), Murrell, Cornelia Randolph (Artist)

Though sometimes forgotten, Irish-born architect Henry Howard had a major impact on nineteenth-century Louisiana architecture. Demonstrating a high degree of versatility, Howard designed plantation homes—including those at Madewood, Woodlawn, Belle Grove, and Nottoway—as well as commercial, institutional, and religions buildings. Equally adept in his use of Greek Revival and Italianate styles, Howard helped establish the latest in fashionable architectural styles and planning principles, particularly in the southern part of the state.

Early Life

Born February 8, 1818, in Cork, Ireland, Henry Howard was the son of builder Thomas Howard. He studied at the Mechanics’ Institute in Cork before immigrating to New York City in 1836. The following year he moved to New Orleans, where he worked as a carpenter for local builder E. W. Sewell for five years. In his autobiography, published in the 1873 edition of Jewell’s Crescent City, Howard notes that, for a short time in 1845, he studied architecture with architect James Dakin and engineer Henry Moellhausen.

Howard received his first major break as an architect in 1844, when he was hired by planter Thomas Pugh to design his new residence on Bayou Lafourche, Madewood. Howard’s design represented the first time that a house form created by a northeastern architect, Minard Lafever, was found suitable for the design of a plantation house. The house resembles a Greek temple, with six Ionic columns across the façade, topped by a pediment, and with two wings flanking the central section. In 1849, Thomas Pugh’s half-brother, William Pugh, employed Howard to remodel his nearby plantation residence, Woodlawn, in the Greek Revival style, making use of the same general arrangement of house and wings as at Madewood. Woodlawn was demolished in the 1940s, but Madewood survives.

Back in New Orleans, Howard was receiving other important commissions, including one for the completion of the two rows of townhouses and stores facing Jackson Square for the Baroness Pontalba. Howard’s rival, architect James Gallier, Sr., began the commission, but the baroness dismissed Gallier in 1849 and hired Howard. Howard’s main contribution to two of the city’s most famous architectural landmarks was the design of the cast-iron verandahs with the baroness’s initials placed prominently within the railings. The verandahs sparked a new trend, with older houses being fitted with similar trim, especially in the French Quarter.

In the city’s most affluent neighborhood, the Garden District, Howard designed a fine Greek Revival villa in 1850 for Robert Grinnan at 2221 Prytania Street. The decade also found him designing the Jefferson Parish courthouse (now Lusher School), located at 719 S. Carrollton Avenue. Built in 1854, the courthouse reflected the Ionic temple front of Gallier Hall, but in a more subdued form. At the same time, Howard was at work on a number of plantation house projects.

The grandest of all the plantation houses that Howard designed was Belle Grove, in Iberville Parish, built in 1857 for John Andrews. Lost to ruin and fire in 1952, Belle Grove was remarkable for its size and for the Howard’s combination of Greek Revival and Italianate styles. The pair of two-story Corinthian porticoes recalled the former while the asymmetrical form suggested an Italianate influence. The house was raised the full height of a basement floor, a feature that made it even more monumental. It was also an important design element for his next commission: Nottoway plantation house. Located a short distance from Madewood, Nottoway was completed for John Hampden Randolph in 1859. Unlike its larger neighbor, Nottoway was entirely Italianate in form and detail, especially in the interior, where the decorative plasterwork depicted three-dimensional forms derived from plants and flowers.

Between 1857 and 1860, Howard partnered with architect Albert Diettel. Several houses were produced during this period, as well as St. Mary’s Assumption Church in New Orleans. Just before the onset of the Civil War, Howard designed the large Italianate residence for Robert Short at 1428 Fourth Street in New Orleans. Compared with Howard’s earlier houses in the city, the Short house was much larger, with an L-shaped plan and an ornate cast-iron verandah covering both stories of the facade. As at Nottoway, the interior decoration, especially the plasterwork, is lavish. Also in 1859, Howard designed his largest urban residence for Cyprien Dufour at 1707 Esplanade Avenue. The house is distinguished by the use of paired columns on the two-story front porch and a balcony supported by decorative brackets on the projecting side bay, much in the manner of those at Belle Grove.

Later Career

Howard left the city during the Civil War, moving to Columbus, Georgia, where he worked for the Confederate States Naval Iron Works. He returned to New Orleans at the conclusion of the war and continued to design large, Italianate houses and commercial buildings. The three-story residence of John T. Moore, built in 1867 at 1228 Race Street, was the last of Howard’s major house designs. The main block of the house rose three full stories and overlooked Coliseum Square.

In 1875, Howard produced his finest commercial building, the Crescent Billiard Hall at 115 St. Charles Avenue. In this design, the Italianate style he had so favored reached its peak. The entire second-floor facade was covered in massive plaster moldings and cornices, with numerous round-arched windows bringing light into the interior. The lower floor, though altered, is still occupied by small shops, as it has been since it was built. For the relaxation of users of the billiard hall, Howard placed a deep verandah around the second floor, though it was later removed.

Despite ill health, Howard continued to work until his death in 1884. Easing the workload somewhat, from 1880 Howard partnered with Henry R. Thiberge, with whom he had previously worked in1860. Though historians have generally considered Howard less significant than his more famous peer, James Gallier, Sr., he outdid his rival in both the number of works produced and the number still standing.