Zydeco

Zydeco is a musical genre that emerged from Black Creole dance music in rural areas of Louisiana.

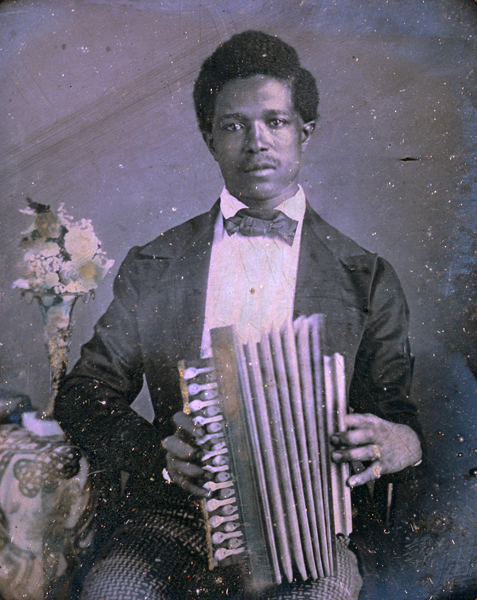

Louisiana State Museum.

Reproduction of a daguerreotype of an unidentified accordion player, 1850.

With its syncopated rhythms, French and English lyrics, and wide range of musical influences, zydeco represents both a Louisiana folk tradition and a still-vital popular music in southwest Louisiana and beyond. In Louisiana, perhaps only young New Orleans brass bands rival zydeco players’ ability to merge the past and present in a sound that still attracts young dancers in the region where the music first started. Zydeco’s enduring popularity can be revealed on a drive through the southwestern part of the state on a typical weekend night, when cars and trucks crowd prairie highways or town streets, and the air around a dance club like the Zydeco Hall of Fame (formerly Richard’s Club) in Lawtell or Slim’s Y-Ki-Ki in Opelousas pulses with the sounds of an accordion and the snap and scrape of a corrugated metal froittoir (washboard). These are the stomping grounds of zydeco, and they are as lively as ever.

Usage of the word “zydeco” to describe the Black Creole dance music of rural Louisiana is fairly recent, dating to the early 1960s, when folklorist Mack McCormick decided on the spelling of the word for his notes to his album A Treasury of Field Recordings. The word quickly gained popularity with musician Clifton Chenier’s landmark 1965 song “Zydeco Sont Pas Sale.” The word “zydeco” is popularly associated with the French phrase “les haricots sont pas salés,” or “the snap beans are not salty.” Snap beans were salted with meat, making the line a colloquial expression for poverty. Similar to writer Albert Murray’s description of the blues, zydeco provides a way for musicians and dancers to fully articulate the deprivations of poverty with intelligence, artistry, and style.

Folklorists Nicholas Spitzer and Barry Ancelet have developed the theory that the language and sound of zydeco are related to traditional music found in parts of West Africa as well as on a number of Indian Ocean islands, especially Rodrigues. In the recorded era, early precedents for the modern zydeco sound are first heard on 1934 field recordings by folklorist Alan Lomax, as well as the early commercial recordings by the legendary Black Creole accordionist Amédé Ardoin. Black Creoles recall early-twentieth-century “la-la” or “French music” house dances, in which an accordion would set the Saturday-night tempo for a roomful of hard-working, hard-dancing couples. Despite segregation, Creoles shared many songs with their Cajun neighbors, and the Cajun and Creole traditions have long borrowed from each other. In later years, traditional Creole music would become popularized by the accordion-fiddle team Bois Sec Ardoin and Canray Fontenot, who like Cajun fiddler Dewey Balfa were early defenders of their culture’s musical traditions.

Zydeco’s hallmark merging of folk traditions and popular music got underway when Louisiana farmers began moving to the oil towns of west Louisiana and east Texas. In cities such as Port Arthur and Houston, accordionists played the music that Black Creoles recognized as their own, but they added rhythm and blues (R&B) and early rock ‘n’ roll elements, such as amplification and even horns. Nobody did this better than Clifton Chenier, who signed to Specialty Records in 1955 and recorded the swampy R&B-laced single “Ay-Tete-Fee.” Although Chenier brought his accordion to Harlem’s Apollo Theater and also recorded for Chess Records, he never attracted a spotlight as bright as that enjoyed by Fats Domino, Ray Charles, and other popular performers of the day. Yet in the 1960s, Chenier teamed up with Arhoolie Records producer Chris Strachwitz and found a new audience on the nascent folk and blues circuit. Meanwhile, his popularity among his home crowd was legendary, and he became known for playing all-night dances for Creoles in Louisiana and Texas, as well as church dances for Louisianans who had migrated to California. Regarded as the “King of Zydeco,” Chenier remained a defining figure in the music until his death in 1987.

Among Chenier’s innovations was the modern froittoir. Early house-dance players scraped a washboard for percussion, but Clifton Chenier and his brother, Cleveland, adapted the instrument by designing a corrugated metal plate that hangs from the player’s shoulders, allowing greater mobility and enhanced rhythmic possibilities. Cleveland Chenier’s mastery of the froittoir (also called rubboard or scrubboard) matched his brother’s accordion prowess. Because of the Chenier brothers’ innovations, the accordion and froittoir are now considered indispensable lead instruments in zydeco, with added rhythm provided by the drums, electric bass, and guitar. Optional instruments include saxophone or other horns, which often signify a distinct R&B approach, and the fiddle, which indicates that the band will opt for more traditional Creole sounds.

When Chenier was ailing during the 1980s, a distinct style of zydeco began to emerge, as did another unforgettable performer. Accordionist Wilson Anthony “Boozoo” Chavis had also recorded in the 1950s, and his signature song “Paper in My Shoe” had become a local hit. But he grew bitter over perceived injustices in the music business and opted to train racehorses on Dog Hill, his farm on the outskirts of Lake Charles. When he finally decided to return to music decades later, his stripped-down zydeco style energized the dance community. Rather than perform on a piano-key accordion, he preferred a diatonic or button accordion, which was more melodically limited but offered a rousing, bouncy sound in Chavis’s hands. Appearing in a Stetson hat and a plastic apron, Chavis sparked a return to the rural roots of zydeco and helped build an ongoing “trail ride” culture, in which horseback riders take to the prairies on Sunday afternoons in a winding procession that culminates in an outdoor dance.

By the time Chavis died in 2001, two schools of zydeco had emerged. Piano-key accordion players generally emulated Chenier and his R&B-laced sound. Among these, the talented musician Stanley “Buckwheat Zydeco” Dural, Jr. has achieved unprecedented fame for a zydeco player, hobnobbing with rock legends such as Eric Clapton, frequently appearing on national television, and recording for major labels. From St. Martinville, Nathan Williams also favors the piano accordion. With his brother Sid Williams running the popular El Sid O’s Zydeco and Blues Club in Lafayette, Williams leads his band, the Zydeco Cha-Chas.

A new wave of younger accordion players picked up and adapted Chavis’s brand of zydeco, none more popular and more influential than Andrus “Beau Jocque” Espre. Beau Jocque taught himself accordion while he was rehabilitating from a back injury. He roared into the zydeco clubs with a style that drew from the punchy accordion work of Chavis but, following Chenier’s example, with added elements of popular music. In Beau Jocque’s case, zydeco mixed with classic rock and hip-hop. Although he toured internationally and received rave reviews in the national music press, his career was cut short when he died in 1999 at the age of 45. Picking up Beau Jocque’s synthesis of zydeco and hip-hop is Keith Frank, who has commanded some of the largest crowds in Louisiana dance clubs for more than a decade.

Another musician influenced by Chavis is Rosie Ledet, one of the relatively few female zydeco accordionists. Ledet follows in the trail of Queen Ida Guillory, a school bus driver who was a child when her family joined the Creole migration from Louisiana and Texas to California. The visibility of zydeco increased in the 1980s when Queen Ida, Clifton Chenier, and Rockin’ Sidney each won Grammy awards. Rockin’ Sidney’s recording “My Toot Toot” became an international novelty hit, accordionist Rockin’ Dopsie was featured on Paul Simon’s Graceland album, and movies such as The Big Easy introduced zydeco sounds to new audiences.

Today, trailblazers include innovators such as the Grammy-winning Terrance Simien, as well as performers who stay close to traditional zydeco sounds like Geno Delafose, who is proficient on both piano-key and button accordions. Once thought to be a dying music genre, Creole fiddling has also enjoyed a revival in the hands of musicians like Cedric Watson and former Zydeco Force bandleader Jeffery Broussard. Although heard at music clubs and festivals around the world, zydeco’s popularity in its home state stands as the best indicator that it will continue to adapt to modern times while honoring its storied past.