Louisiana Lottery

Beginning in 1868, the Louisiana Lottery operated with much controversy and opposition until 1897.

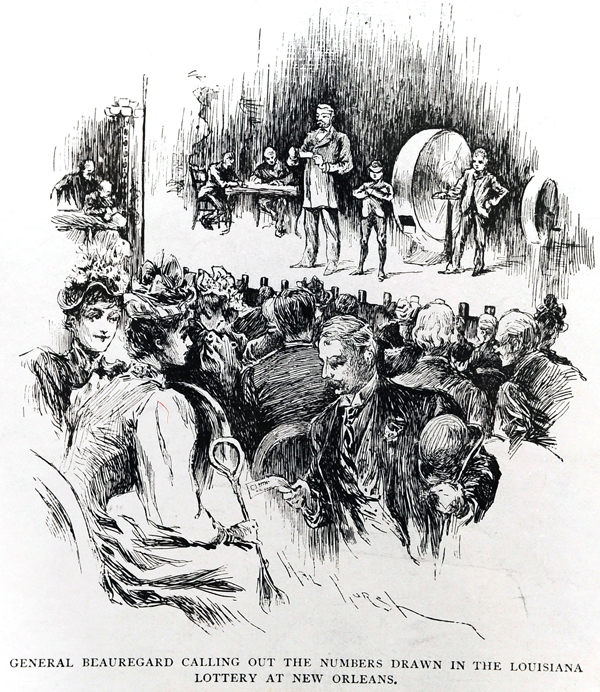

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

General Beauregard and The Louisiana Lottery. Hurst, Hal (delineator)

Between 1868 and 1893, the Louisiana Lottery Company operated one of the largest and most financially successful lotteries in the United States. It was also among the most controversial drawings in the country; its history characterized by charges of bribery and corruption. Granted a twenty-five-year charter by the state legislature in 1868, the company sold tickets across the nation. Drawings were held in New Orleans on a daily, weekly, monthly, and semiannual basis. Despite its financial success and popularity, rumors of political bribery and in-house theft plagued the company’s operation, eventually leading to federal legislation prohibiting the interstate sale of lottery tickets. The action of the U.S. Congress reduced company’s income by 90 percent and, in 1892, Louisiana voters refused to support a state constitutional amendment extending the lottery’s intrastate activities for another twenty years.

Development of the Lottery

Following the Civil War (1861–1865), Louisiana politicians were open to the idea of a lottery as a means of generating desperately needed revenue for the state budget. Charles Howard, a former agent of the Kentucky Lottery, offered Governor Henry Clay Warmoth a $40,000 annual payment to the state’s treasury for the exclusive right to operate a lottery in Louisiana. On December 31, 1868, the corporation opened for business in a former bank building on the corner of Union Street and St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans.

Every drawing was accompanied by a pageantry that would rival modern extravaganzas. To enhance its credibility, Howard hired two former Confederate generals—P. G. T. Beauregard and Jubal Early—to supervise the drawings. They sat on a stage with a large cylinder that had been filled with capsules containing numbers. Every so often, two young African Americans would pull out capsules from the container and hand them to Beauregard or Early. After checking the numbers, young ladies dressed in hoop skirts posted the numbers on a large board for the audience to see. Tickets were sold across the United States and thousands of sales receipts were sent to New Orleans. In and around New Orleans, ticket holders often asked clergy members to bless their tickets. Others frequently sought out Voudou priests to help them identify the winning number combinations.

Lacking the legislative authority to audit the corporation’s books, state authorities remained in the dark about the lottery’s financial operations. But according to T. Harry Williams and other post-Reconstruction students, yearly lottery sales in the 1880s totaled nearly $23 million, and the corporation possibly cleared as much as 43 percent from the ticket sales. The corporation enjoyed additional revenue if it failed to sell all of its tickets before the drawings; the unsold tickets were placed into the barrel, enabling the company, in many instances, to win its own prize money.

Lottery officials were experts when it came to creating a positive image of the corporation. Whenever the Mississippi River broke through its levees, the lottery used its own vessel, the Dakotha, to quickly transport men and materials to repair the crevasse and distribute food and funds to flood victims. During the state’s frequent bouts with yellow fever, corporate officials hired scores of unemployed workers to collect and bury the dead. Moreover, the lottery paid newspapers large amounts of money to advertise its drawings or announce the winning numbers. Few of the many cash-strapped papers were willing to risk losing this revenue stream by criticizing the corporation.

The Lottery and the Legislature

The political arena proved much more difficult for the corporation to control. From the beginning, legislators seized the initiative in demanding to be paid for their support of the lottery. To back up their demands, politicians introduced bills threatening the monopoly that the company enjoyed, then withdrew them when they received a cash “contribution.” More often than not, committee chairmen or individually powerful legislators supplied the cash to undercut antilottery legislation.

In 1878 and 1879, however, the lottery faced opposition that its supporters could not control; legislation outlawing its operation passed in both houses of the legislature. Even though he believed the bill was unconstitutional, Governor Francis T. Nicholls signed it, indicating that he had had enough of the corporation’s role in promoting bribery. Almost immediately, the lottery corporation appealed to the Federal District Court in New Orleans, where it successfully argued that its operation had not exceeded the charter granted by the state. Subsequently, lottery officials used all of the political leverage they could muster to obtain protection from its critics. As a result, lottery officials were successful at the 1879 Constitutional Convention when they attempted to make the lottery’s charter part of the state constitution. Then, in an unprecedented show of force, the convention attendees moved up the state’s 1880 general election to coincide with the vote on the amendment. In so doing, the lottery cut one year off of Nicholls’s gubernatorial term.

The Lottery’s Demise

The 1880s marked the high point of the lottery company’s financial and political power. With the support of the Louisiana State Treasurer, Edward A. “E.A.” Burke, gaming officials had little to fear from its critics. All of this changed, though, by 1890, when the corporation again found itself engaged in a struggle for its existence. In 1887, following a bitter intraparty gubernatorial primary, voters reelected Nicholls governor. He made it known that he would not support an extension of the lottery’s charter, hoping it would die a natural corporate death in 1893. John A. Morris, the corporate leader of the lottery, had other ideas. After assuring Nicholls that he had no intention of reviving his gaming company, Morris used legislative supporters to offer the state treasury an annual payment of $750,000, if he could extend the lottery’s operations for another twenty years.

Battle lines were quickly formed in the state legislature. In one of the state’s most contentious legislative sessions, lottery supporters secured a constitutional amendment extending the life of the corporation, with no votes to spare. Governor Nicholls refused to accept defeat and vetoed the amendment, telling voters, “At no time and under no circumstances will I permit one of my hands to aid in degrading what the other was lost in seeking to uphold—the honor of my native state.” “Were I to affix my signature to the bill,” Nicholls continued, “I would indeed be ashamed to let my left hand know what my right hand had done.” Antilottery supporters were ecstatic. But several months later, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that Nicholls had exceeded his authority and ordered the secretary of state to place an amendment on the ballot for the upcoming 1892 elections.

For the moment, the supporters of the extension could rejoice; their triumph, however, proved short-lived. At the national level, members of the U.S. Congress had been following the lottery battles in Louisiana. The fact that, outside of New Orleans, Washington, D.C., ranked second in the number of lottery ticket sold undoubtedly heightened their interest. President Benjamin Harrison thought that the problem deserved the Congress’s special attention. In his 1889 inaugural address, he had asked the U.S. postmaster general to investigate the use of the mails by gaming corporations. Later, he requested that Congress give the postmaster the power to regulate “the transmission through the mails of lottery advertisers and remittances.”

Throughout the United States, sentiment favored antilottery legislation, and, on September 19, 1890, the president signed legislation granting the federal government control over state lotteries and their use of the mails. The Louisiana lottery attempted to overturn the legislation by appealing to the federal courts, but in December 1892 the court ruled in favor of the postmaster. After losing their appeal, lottery representatives asked Louisiana officials to withdraw the amendment granting the company an extension of its gaming activities. A short time later, E. A. Burke attempted to revive the lottery in Honduras where he had fled around 1891 after being indicted for stealing nearly $1.5 million from the state. His efforts failed to generate sufficient sales abroad, however, and the corporation passed into history by the end of the century.