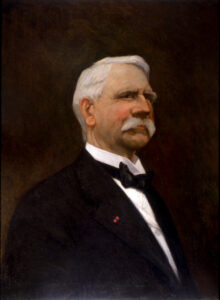

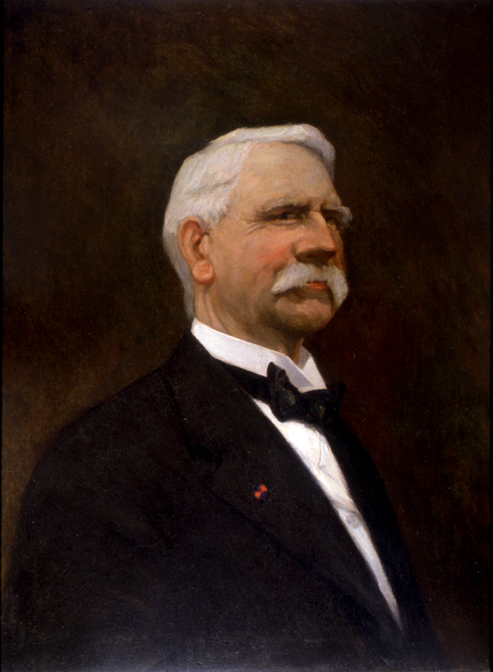

Henry Clay Warmoth

Henry Clay Warmoth was the first governor of Louisiana under Radical Reconstruction.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Governor Henry Clay Warmoth. King, Paul (Artist)

Henry Clay Warmoth was Republican governor of Louisiana at a pivotal moment in the state’s history: the first years of Radical Reconstruction (1868–1872). His administration bore the full brunt of the reactionary forces of Counter-Reconstruction spearheaded by the Knights of the White Camellia (KWC), the terrorist arm of the state Democratic Party. Warmoth never resolved the daunting array of problems involved in competing with a rival party dedicated, not just to defeating Republicans at the polls, but to their complete and utter destruction.

Warmoth was born in the southern Illinois town of McLeansboro to Isaac Sanders Warmoth, a saddler, and Eleanor Lane. A few years after his birth, the family moved to Fairfield, Illinois, where the elder Warmoth became a successful businessman and justice of the peace. Young Warmoth attended local schools, read law books in his father’s office, and frequented court sessions. When he was eighteen he moved to Lebanon, Missouri, where he gained admission to the bar and became a county attorney.

When the Civil War broke out, Warmoth enrolled in the Missouri militia and in November 1862, despite being only twenty years old, entered the Union Army as a lieutenant colonel of the 32nd Missouri Infantry. In January 1863 he joined the staff of political general John A. McClernand, a corps commander in General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of Tennessee. Warmoth suffered a serious wound in the siege of Vicksburg. During his convalescence, Grant ordered his dishonorable discharge from the army, alleging that he had been absent without leave and that he had circulated exaggerated accounts of Union losses during his recovery. Grant had little use for political generals such as McClernand, and the charges against Warmoth probably had more to do with Grant’s disdain for McClernand than anything Warmoth had done. Warmoth appealed his case to President Lincoln and won reinstatement. Years later, however, this seemingly minor episode may have influenced the course of Louisiana Reconstruction.

In 1864 Warmoth was ordered to the Department of the Gulf, where General Nathaniel P. Banks appointed him judge of the Gulf Provost Court in New Orleans. He left the army and in early 1865 set up a law practice in New Orleans, where he focused on legal issues raised by the Union occupation. Warmoth joined the Free State Party, which was the forerunner of the state Republican Party. Tall and handsome with a magnetic personality, he became a leading figure in Free State/Republican circles. In September 1865 Louisiana Republicans elected him the state’s unofficial “territorial” delegate to Congress. Because of the long federal occupation, northerners such as Warmoth—soon to be called carpetbaggers—were important players in Louisiana Reconstruction politics. In early 1868 their influence nominated Warmoth for Republican governor. That April he easily defeated conservative Republican James G. Taliaferro, a unionist/scalawag, by 64,941 votes to 38,046.

Warmoth took office in July 1868 amid crisis. It was a presidential election year, and the forces of Counter-Reconstruction launched an all-out effort to win Louisiana for Democrat Horatio Seymour against Republican Ulysses S. Grant. The Knights of the White Camellia (KWC), akin to the Ku Klux Klan, resorted to terrorist assaults—whippings, shootings, riots, and mass murder—to win the state for Seymour. Federal authorities concluded that the KWC killed a thousand people, overwhelmingly black Republicans, in the deadly campaign. Terrorism worked. Seymour carried the state by an incredible margin of 80,225 to 34,859. In the brief span of seven months between Warmoth’s election in April and the presidential election in November, the Republican electorate in the state dropped by 30,000 votes.

Fortunately for Louisiana Republicans, the presidential election was not a state election. If it had been, Radical Reconstruction in Louisiana would have been over. The election drove home the message that conservative whites could destroy radical government through intimidation and terror. Warmoth and his party responded with bold initiatives to protect the regime. The legislature created a state militia and put the New Orleans Metropolitan Police under the governor’s control. Lawmakers further endowed the governor with broad powers to supervise elections and created a state returning board that could alter election returns in the event of fraud or intimidation. New laws also enabled the governor to appoint many officials in the hinterlands, avoiding the uncertainty of elections. These measures involved Warmoth’s government in a contradiction it never resolved. The danger to democratic government posed by terrorists in the Democratic Party was as real as the region’s sultry heat. On the other hand, the police and election apparatus constructed by Warmoth and his party in response to the terrorist threat was as destructive of democratic processes as the actions of the terrorists themselves. What governing party in American history could be trusted with a returning board legally empowered to alter election returns at will? The answer is self-evident.

Fights over patronage further undermined the legitimacy of Warmoth’s administration. The core problem confronting Warmoth and his party was that their Democratic enemies rejected the legitimacy of radical government based upon black votes. Like governors in other southern states, Warmoth attempted to “whiten” the Republican Party by giving jobs to Democrats and luring whites into the radical party. Alas, his largess did little to weaken white opposition to radical government, while it provoked bitter opposition among job-hungry Republicans.

In 1871–72, angry Republicans revolted against Warmoth’s leadership. Key opposition leaders were black lieutenant governor Oscar J. Dunn and carpetbaggers William Pitt Kellogg (former collector of the port), James F. Casey (collector of the port), and Stephen B. Packard (U.S. marshal). These men and their followers controlled the immense federal bureaucracy in New Orleans, the most lucrative source of public jobs in the state, and came to be called the “Custom House Ring.” The fact that so many of his opponents held federal jobs, as opposed to state jobs, made them immune to the kinds of pressures that a governor could normally bring to bear on recalcitrant members of his party.

The factional struggle, with its coups and countercoups, took on the character of banana-republic opera buffa. In August 1861, for example, U.S. Marshal Packard employed Gatling guns and federal troops to bar the Warmoth faction from the Custom House, site of the Republican state convention. Then, in early 1872, Packard arrested Warmoth and eighteen lawmakers. Warmoth obtained bail and struck back, sending the Metropolitan Police to capture the state house. Such shenanigans created a national scandal that discredited Reconstruction not only in Louisiana, but also in the entire South. Warmoth emerged the loser in the struggle, in large part because Collector James F. Casey was the brother-in-law of his old enemy Ulysses S. Grant, now President Grant.

In the fall of 1872, a desperate Warmoth switched parties, supporting the Liberal Republican Horace Greeley in the presidential contest and Democrat John D. McEnery for governor of Louisiana. His course led to a disputed election that further poisoned state politics and undermined the legitimacy of Republican government. In December 1872 the state House of Representatives voted to impeach him. The Senate failed to convict him, but he was suspended from office during the impeachment, and black lieutenant governor P. B. S. Pinchback served as acting governor during the remaining weeks of his term. (Pinchback was the only black man to serve as governor during Reconstruction.) After the disputed election, Warmoth returned to the Republican Party and remained active in politics until the end of the century. He served briefly in the state House of Representatives in 1876, was a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1879, was Republican candidate for governor in 1888, and was collector of the Port of New Orleans in 1890–93.

Warmoth acquired wealth during his governorship and a reputation for corruption along with it. “I don’t pretend to be honest,” he said honestly. “I only pretend to be as honest as anybody in politics.” He slammed the hypocrisy of Louisiana businessmen who publicly protested the corruption of state lawmakers while secretly buying their votes. “I tell you these much-abused members of the Louisiana legislature are at all events as good as the people they represent. Why, damn it, everybody is demoralizing down here. Corruption is the fashion.”

After Reconstruction, Warmoth married a New Jersey heiress who bore him three children. He purchased part-ownership in a Plaquemines Parish sugar plantation and helped establish the Magnolia Sugar Refining Company. In the 1890s he was a lobbyist for the Louisiana Sugar Planters Organization. He eventually sold his sugar plantation and lived out his life in New Orleans. He had carefully preserved a wartime diary and a vast store of personal papers related to Reconstruction. In 1930, shortly before his death, he published War, Politics and Reconstruction: Stormy Days in Louisiana, one of the best accounts of Reconstruction written by a participant. His manuscripts are in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.