Barthélémy Lafon

Barthélémy Lafon enjoyed a long and diverse career in Louisiana as an architect, builder, engineer, surveyor, cartographer, town planner, land speculator, publisher, and pirate.

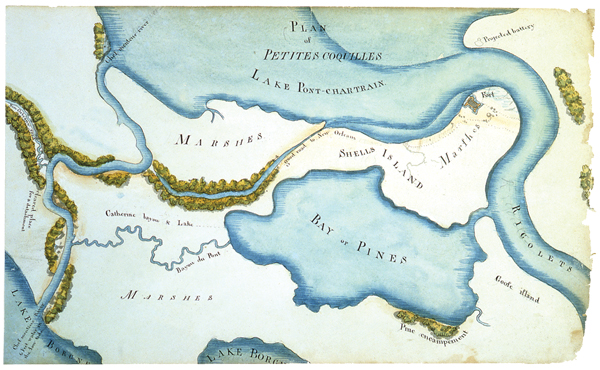

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Plan of the Land around Fort Petites Coquilles. Barthelemy Lafon

Barthélémy Lafon enjoyed a long and diverse career in Louisiana as an architect, builder, engineer, surveyor, cartographer, town planner, planter, land speculator, publisher, and pirate. Born in France, he arrived in New Orleans about 1789. The Spanish colonial town was rebuilding after a disastrous fire in 1788, and an industrious entrepreneur of varied talents could expect numerous opportunities. Lafon’s skillful architectural renderings, competency in surveying, and understanding of town planning suggest that he was well educated in French institutions. He engaged in scholarly and scientific endeavors and amassed a library containing 445 volumes in several languages on topics ranging from architecture and literature to alchemy, exorcism, and secret codes.

Although best known as an architect and planner, Lafon published New Orleans’s first almanac, Calendrier de Commerce de la Nouvelle Orlèans Pour l’Année 1807, as well as Annuaire Louisianais Pour l’Année 1809. He served on the New Orleans City Council from 1808 to 1810. In the military, his career included rising to captain in the Second Regiment Militia by 1806, surveying the city’s defenses between 1810 and 1815, and preparing fortifications related to the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.

Lafon undertook numerous public works projects, the first being repairs to the city jail damaged in a 1794 fire. Four years later, he was called as an expert to appraise the work accomplished at the Presbytere and Cabildo. Between 1797 and 1799, he improved the “bridges” or covered gutters along the city streets, and in 1802, he repaired riverfront levees.

Construction of a tile-roofed, wood-frame fish market near the levee was an important contract awarded to Lafon in 1798. For the nearby meat market, Lafon submitted plans to the city in 1808 with estimated construction costs of $18,900. The masonry building featured rows of brick pillars supporting a twelve-foot overhang below a roof of slate. Although substantial, the market was destroyed in the devastating hurricane of 1812.

Lafon’s involvement in land speculation and development was complex and litigious. He acquired a plantation at Chef Menteur in 1801 and erected a dwelling and outbuildings a few years later, and he purchased property at the corner of St. Louis and Burgundy streets where he built a home known as 60 St. Louis Street. He owned land in Plaquemines Parish (1807), Opelousas (1811), and Donaldsonville (1816), and lots in Faubourg Annunciation (1808), and he made claims on other properties. In 1798, he petitioned Spanish Governor Gayoso for about ten acres of vacant land near the foot of what is now Canal Street, where he planned to establish the city’s first foundry. His claim was later disputed by city officials, who, in 1807, proclaimed the property a “commons” between the town and its new upriver suburb, Faubourg St. Mary. A bitter fight ensued and the city finally settled with Lafon for $15,000, but final payment was made only eleven days before his death.

Lafon’s first important private commission was probably for a house at the corner of Conti and Decatur streets for Mademoiselle Jeanne Macarty. The 1794 contract specifies a building typical of colonial New Orleans. Stores were on the brick ground level, while the colombage (half-timber) second floor contained plastered formal rooms with wood-paneled chimney breasts. In 1797, merchant Jean Baptiste Riviere commissioned a larger house at the corner of Bienville and Decatur streets. While similar to the Macarty house, the Riviere home was made taller by the addition of an entresol and more elegant by the inclusion of especially fine details, such as carved mantles, a rose window, and a pediment with sculpture.

Both projects resulted in acrimonious disputes that may have affected the architect’s reputation, perhaps accounting for the dearth of documented buildings after 1808, as well as Lafon’s propensity to undertake other kinds of projects. When he decided to return to the building trades in 1816, he advertised, “The number of houses which he has built in this city, and the elegance and solidity of which are proved at the first sight, cannot fail to secure him a preference over every other architect of this city. He will not relate them here: they are known by everybody.” It is regrettable that the buildings were not named, but several extant houses are attributed to Lafon based on stylistic qualities and documentary evidence.

The most notable of these is the Pedesclaux-Lemonnier House at the corner of Royal and St. Peter streets. Popularly known as “Sieur George’s House” (from a George Washington Cable story) and the city’s “first skyscraper” (the fourth story was added in the 1870s), the building belonged to two notable citizens—notary Pierre Pedesclaux, who began the project after the fire of 1794, and Dr. Yves Lemonnier, who completed it in 1811. Lafon had his office at “7 Rue Royale,” and in 1807, he rented most of the building under a contract that suggests he was to complete the house. In 1811, when Pedesclaux’s financial difficulties brought the building to auction, the advertisement characterized the property as being in an “incomplete and unsuitable state.” Purchasers Lemonnier and Grandchamps immediately hired Arsene Lecarrier Latour and Hyacinthe Laclotte to repair and complete the structure. Although all of these French-born architects were capable of designing a refined townhouse, the elegant but rather studied composition suggests that Lafon’s design was largely followed by his successors.

Other important townhouses of the late Spanish-colonial period attributed to Lafon based on stylistic similarities to his documented works include the Barthelemy Bosque House at 616 Chartres Street, built about 1795; a late 1790s home for Vincent Rilleaux at 343 Royal Street; and the Joseph Reynes House at the corner of Chartres and Toulouse streets, built about 1795.

The 1806 Joseph Zeringue house (demolished) is perhaps the best-documented of Lafon’s designs in the Louisiana plantation vernacular. Consisting of two main living spaces and a rear gallery flanked by cabinets, the colombage dwelling was raised on brick piers and fronted by an eight-foot gallery. Around 1804, Lafon built a smaller, rougher version for himself on his property at Chef Menteur.

Lafon’s work as a surveyor was extraordinary. For at least two decades, he worked for private clients and served as deputy to the surveyor general for Orleans County (1805–1809). In 1805, he completed work on one of the earliest and most accurate maps of Louisiana—Carte Générale du Territoire d’Orleans Comorenant Aussi la Floride Occidentale et une Portion du Territoire du Mississippi. Available in cloth and paper, the map was displayed at Lafon’s office in the Pedesclaux building and was distributed widely, selling in New York for $8. He later prepared plans of English Turn (1814), the Balise (1814), Fort St. Jean (1814), and Fort Bower (n.d.) on Mobile Point. His 1816 map of New Orleans details the nearby countryside, as well as the new suburbs, some of which he helped to create from the plantations arrayed around New Orleans.

Most influential were the 1806 and 1807 plans made for the subdivision of Delord-Sarpy Plantation, which enlarged Faubourg St. Mary and created Faubourg Annunciation further upriver. Reminiscent of complex eighteenth-century French plans, Lafon’s second design incorporates circles with radiating streets, diagonal boulevards to provide vistas, and space for important public buildings. There were tree-lined streets and parks, canals and basins for drainage and beauty, and a place for amusements—Tivoli Circle (now Lee Circle). It was Lafon who set the location for St. Charles Avenue (Nyades) and named streets after the Greek muses. In his 1807 plan for the new city of Donaldsonville, he used many of the same features while fitting the plan to a curving site and adding a crescent shape plaza. These plans establish Lafon as both creative and conversant with European planning concepts.

Three years before his death, Lafon’s involvement with a colony of pirates at Galveston, Texas, was widely publicized. There is some evidence that he had been involved with the famous Jean Lafitte and his cohorts long before, but his actions as a pirate in 1817 are well established, especially with regard to his ownership of a former Spanish schooner named Carmelita, which was characterized as having been “captured by pirates or robbers on the high seas.”

Lafon died in 1820 at the house on St. Louis Street while the city was in the midst of a major yellow fever epidemic. He never married, but fathered two children, Jacques Barthélémy and Carmélite, by the free woman of color Modeste Foucher. Although historians have postulated that he was the father of local philanthropist Thomy Lafon, there is no evidence to support this. His estate was thought to be large, but after years of lawsuits, in 1826 it was declared “insolvent and unable to pay the legacies and debts.” His legacy was more than monetary, however. In spite of what seem to have been a contentious nature and questionable business ethics, he made an indelible mark on the city, not only through his remaining buildings but, more important, through the city planning projects that shaped New Orleans.