San Francisco Plantation

The San Francisco Plantation name is derived from the term "sans fruscins" meaning "without a cent" or "having lost everything," possibly alluding to the high cost of the house.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

San Francisco Plantation House. Johnston, Frances Benjamin (Photographer)

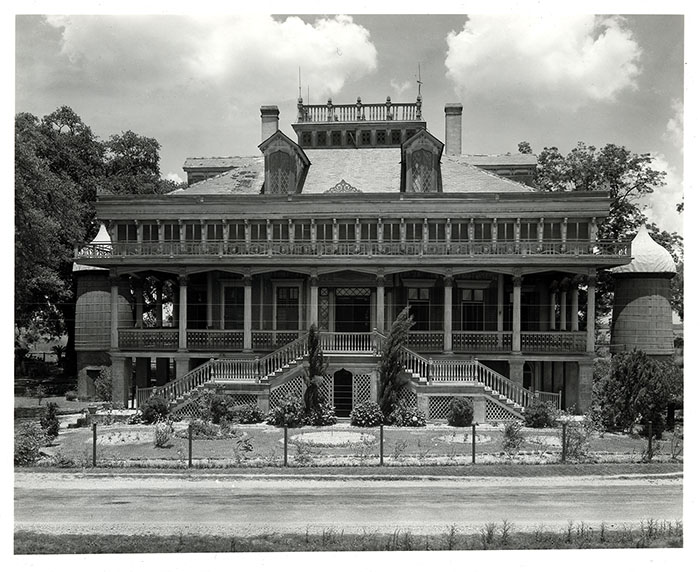

San Francisco plantation house, located along River Road in Garyville, Louisiana, displays a distinctive silhouette and flamboyant decoration that have caused its style to be dubbed “Steamboat Gothic.” In 1830 Edmond Bozonier Marmillion bought this plantation land for $100,000 from Elisée Rillieux, a free man of color; Marmillion probably began construction of his house shortly after the crevasse of 1852, completing it in 1856, the year he died. One of his sons, Antoine Valsin Marmillion, took over management of the sugar plantation and, with his German-born wife, Louise von Seybold, gave the house its interior decoration. They named the plantation St. Frusquin—not a real saint but a play on sans fruscins, meaning “without a cent” or “having lost everything,” possibly alluding to the high cost of the house. When Achille D. Bougère purchased the plantation in 1879, he renamed it San Francisco.

Architectural Features

The first floor is constructed of brick; the second floor is brick between posts. A wide double flight of stairs leads to the principal living spaces on the second floor. The symmetrical placement of the stairs and the central entrance suggest that the house has an American central-hall plan, but that is not the case; instead, the entrance leads to rooms that connect en suite. Edmond Marmillion chose a room layout that was conventionally Creole, but which, by that time, was considered out of date. Moreover, he followed Creole tradition by using the ground floor for dining and service rooms and the upper for the principal living spaces. In contrast to this conventional solution (but one that was practical, for it suited the climate), the exterior displayed the latest in American picturesque taste: a gallery with fluted Corinthian capitals and Tudor arches, a decorative balustrade screening the band of louvered windows that ventilate the attic, an overscaled projecting and bracketed cornice, ogee-arched dormer windows, and a widow’s walk raised above a row of ogee-shaped windows. The exterior is painted in blue, peach, and pistachio, as Creole families favored colorfully painted houses, in contrast to the Anglo-American preference for white or pastel colors. Cisterns with reconstructed onion-domed copper covers stand on each side of the house; water was pumped from them to a tank in the attic, which led to sinks through a system of pipes.

Valsin and Louise Marmillion, rather than Edmond, were probably responsible for the delicate renderings of flowers, garlands, birds, and putti painted on ceilings in five of the rooms, the striking Pompeiian decoration of some doors (attributed by some to Dominique Canova, although without documented evidence), the false wood patterns on doors and trim, and false marbling on the mantels. Some of this work is original to the house, and some has been repainted, based on the evidence of fragments discovered during the restorations in the 1970s under architect Henry W. Krotzer Jr.

Postbellum Operations

No buildings survive from the plantation’s wealthy years before the Civil War, but Valsin Marmillion was known for severe treatment of his slaves. Although the plantation was profitable when Marmillion inherited it, the death of his father as well as six of his siblings convinced him that the place was unhealthy. He and his younger brother Charles attempted to sell San Francisco in 1859, but a sister-in-law disputed the sale. When the case was finally settled in 1861, the war prevented any further action. Valsin died of tuberculosis in 1871, and Charles died four years later. After they purchased San Francisco, the Bougère family experienced financial struggles typical of Louisiana sugar producers after the war. Between 1909 and 1976, the house was owned by a family named Ory, who did little to alter the structure other than install modern bathrooms and a modern kitchen.

The San Francisco plantation house inspired Frances Parkinson Keyes to write her 1952 novel, Southern Gothic, set in the years spanning the end of the Civil War until the Great Depression. The characters’ lives reflect the upheavals that social, economic, and technological changes brought to River Road plantations such as San Francisco. Two years later, the Orys leased San Francisco to a couple who opened the house for tours and maintained the structure for the next twenty years. The house and grounds were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

Marathon Oil purchased the plantation in 1976 and funded a $2 million restoration project that spanned three years. San Francisco now sits incongruously close to oil-industry structures, but it might not be standing at all if community residents had not protested in the 1930s, when initial plans for new river levees would have razed the house. The Army Corps of Engineers curved the levee to save San Francisco’s house, but the gardens that fronted the mansion were lost. Cabins that housed enslaved workers, dating from the 1830s and 1840s, have been moved to the grounds, and a garden has been reestablished behind the main house. The nineteenth-century sugar mill was dismantled in 1976 and sold to a corporation in Panama. For more than fifty years, the house has remained a popular tourist destination along River Road.