Magazine

Twentieth Century Millennial: Revisiting Faulkner’s Mosquitoes

Published: November 17, 2017

Last Updated: February 21, 2019

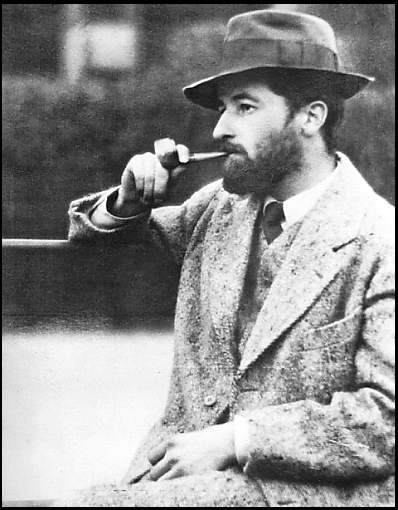

Faulkner in full bohemian mode, Paris, 1925.

First, I googled whether I am in fact a millennial. According to the Urban Land Institute, the DC nonprofit that originally issued the report, I’ve just barely aged out of the category (defined as twenty-five to thirty-four year olds). But according to my forty-something-year-old friends, I am a Prius-driving, part-time-jobbing, no-child-bearing millennial through and through.

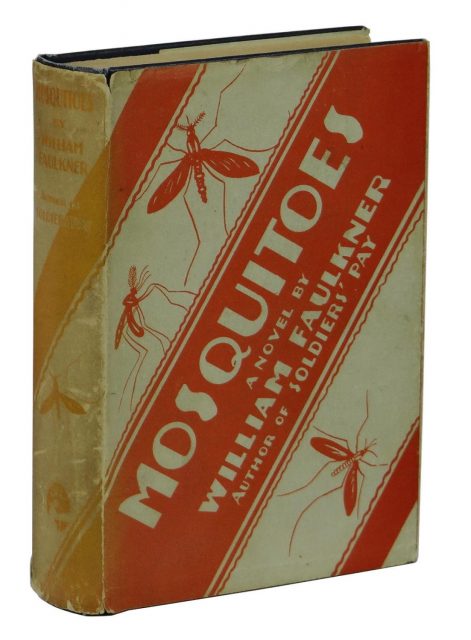

The second thing I did was I reread William Faulkner’s second novel, Mosquitoes. It’s a New Orleans–set, un-Faulknerian comedy of errors that was generally ignored upon publication, and has never received much attention beyond deep-cut southern lit scholars and curious Crescent City citizens.

The key to understanding, loving, and accepting Mosquitoes—despite its faults, and it has many—is that Faulkner wrote the novel when he was last century’s millennial par excellence. In January 1925, at the age of twenty-seven, the taciturn poet with nicotine-tarnished fingers, shaggy hair, and an adolescent’s mustache fled Oxford, Mississippi, for New Orleans, a taciturn poet with nicotine-tarnished fingers, shaggy hair, and an adolescent’s mustache. Sound familiar?

Over his sixteen months in the city, he enjoyed treading barefoot, drinking too much corn liquor, falling in unrequited love, and raising hell (shooting BBs from his apartment window at nuns and other Jackson Square pedestrians was a preferred pastime). He also devotedly clacked away on his typewriter, churning out a collection’s worth of short stories alongside a pair of novels written, as he’d recall decades later, “for the sake of writing because it was fun.” Twenty-first-century millennial translation: You Only Live Once.

First published in 1927, Mosquitoes takes place during the late summer, when those infamous bloodsuckers force New Orleanians to slap, swat, and scratch their way through what Faulkner calls “the decadent languor of August.” The novel’s protagonist is Ernest Talliaferro, a widowed women’s clothing wholesaler who, like Faulkner, has changed his name (née Tarver) and adopts the demeanor of a world-weary aesthete (as a young man, the future Bard of Yoknapatawpha famously affected the role of a World War-scarred veteran, complete with phony cane and fake officer’s uniform).

Bored with brassieres and evening gowns, Talliaferro finds refuge within a local circle of misfit bohemians and benefactors. He accepts an invite from Patricia Maurier, a renowned patron of the arts, to join a Lake Pontchartrain excursion aboard her yacht, the Nausikaa, for a few days of respite from their mosquito-plagued surroundings. They’re accompanied by a handful of straw-hatted and batik-patterned artists and hangers-on—like Mark Frost, a cerebral poet as icy as his name, and the mysteriously mononymous Gordon, a dark-souled sculptor with a Soviet beard—stand-ins for Faulkner’s real-life acquaintances, many of whom were none too happy at their portrayal (Faulkner modeled the bloviating novelist Dawson Fairchild on his mentor Sherwood Anderson, leading to their inamicable split).

The voyage is a disaster in the waiting. Nausikaa is a play on Nausicaa, a character from Homer’s Odyssey whose name in Greek translates to “burner of ships” (the yacht’s name also sounds distressingly similar to “nausea”). Faulkner’s ship of fools sets off with “nothing to look at save one another, nothing to do save wait for lunch.” For four days the passengers partake in Victrola dance parties, countless hands of bridge, and the monotony of local citrus—their host bought caseloads of grapefruit on the cheap, which the guests consume, meal after meal, until the fruit becomes as “sinister and bland as taxes.” But what they do most of all is gossip, gab, and flirt and flirt and flirt, with more and more candor and cruelty as the hours tick by: “Talk, talk talk: the utter and heartbreaking stupidity of words. It seemed endless, as though it might go on forever.”

On day two, the Nausikaa goes full Gilligan—marooned at sea—after Maurier’s nephew removes the steering gear in order to fashion a smoking pipe. The passengers unsuccessfully attempt to oar the boat to shore. While awaiting a tugboat, the winds shift, carrying a cloud of mosquitoes toward the boat. The crimson-splattered slapping and swatting and scratching, along with the flirting and flouting, recommences. “Where do they carry so much blood,” one character wonders. “They’ve found where we are and that we are good to eat,” another despairs.

First edition of Mosquitoes, published by Boni and Liveright, 1927.

Despite this nightmarish scenario, my rereading of Mosquitoes did cultivate a desire to explore Lake Pontchartrain and its swampy environs—up till now I’ve always been more comfortable staring out at the Mississippi. Faulkner richly describes the morning’s “quiet fathomless mist.” “A worn cold moon” silvering water that’s “warm as warm.” The shore’s “[h]uge cypress roots thrust up like weathered bones out of a green scum and a quaking neither earth nor water, and always those bearded eternal trees like gods regarding without alarm this puny desecration of a silence of air and earth and water.”

By the time their rescue arrives, it’s evident that few, if any, of the passengers have come to comprehend they are more parasitic than the book’s titular creatures. Despite all the flirting and philosophizing, none of the characters come off as someone you’d like to join for a julep. “All artists are kind of insane,” one quips during the height of hopelessness. “Almost as insane as the ones that sit around and talk about them,” another retorts. Faulkner’s message is clear: We are the mosquitoes, and the mosquitoes are us.

Though he spent less than two years in the city, and rarely found time to return, William Faulkner is identified with New Orleans like few other authors—a bookstore, building, and literary festival all carry his name. We claim him largely due to his global stature, of course, but I’d like to think that the millennial from Mississippi understood New Orleans like few other visitors. Despite frequent, provincial-minded protestations otherwise, New Orleans is, was, and will always be a city. And cities attract and nurture artists—be they poets and painters, or craft cocktailers and yoga teachers—like nowhere else. The millennial hordes that flood the city each year come in the name of carving out an art-filled life, maybe even a career, just as I did back in 2000. Millennials will raise the median rent, demand that groceries stock kale as if they invented it, and force change upon a resistant city, just as they have for well over a century. In New Orleans, as elsewhere, each and every one of us is a bloodsucker. What matters is how much blood we give back.

—

Rien Fertel lives in New Orleans and St. Martinville. He is the author, most recently, of The One True Barbecue, and is currently writing a book about southern rock.