NOLA 300 Music

Canal Street: A Hemispheric Boundary

That uptown–downtown negotiation wasn’t just a local one. It was tectonic: the two great cultural regions of the hemisphere were crunching into one another.

Published: September 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Uptown.

Uptown.

A whisper, sampled, begins “Neck of the Woods” (2005) by Bryan “Birdman” Williams and Lil Wayne. Uptown, it says, with the syllable “up-“ on the upbeat and “town” on the one. It’s the first and last thing you hear, in a territory-marking rap: Well let me take you to my neck of the woods, to my hood / Show you what we livin’ like.The uptown–downtown dichotomy in New Orleans goes far beyond turf battles in hiphop, of course. For one thing, it’s basic to the birth-of-jazz polemic. This has generally been spoken of in local terms: in a post–Plessy v. Ferguson environment that collapsed a three-caste racial system into two, musically literate downtown Creole musicians (e.g., Sidney Bechet), who were French- or Spanish-surnamed, Catholic, and often though not necessarily lighter-skinned, found themselves playing with musically illiterate uptown African-American musicians (e.g., Louis Armstrong) who were English-surnamed, hot-playing Protestants, two generations or so off the plantation.

But that uptown–downtown negotiation wasn’t just a local one. It was tectonic: the two great cultural regions of the hemisphere were crunching into one another.

***

The most exasperating cliché about New Orleans—apart from the dreaded gumbo metaphor, which is at least arguably true—is that it’s the “northernmost town of the Caribbean.” Which sounds good, but unfortunately, it’s romanticism; New Orleans is on the Gulf of Mexico, not the Caribbean.

But we can all agree that New Orleans is the northernmost edge of something. Specifically, New Orleans is the northernmost town that shuts down for Carnival (okay, along with Mobile), because, pardon my italics: New Orleans was the northernmost edge of the Catholic portion of the hemisphere.

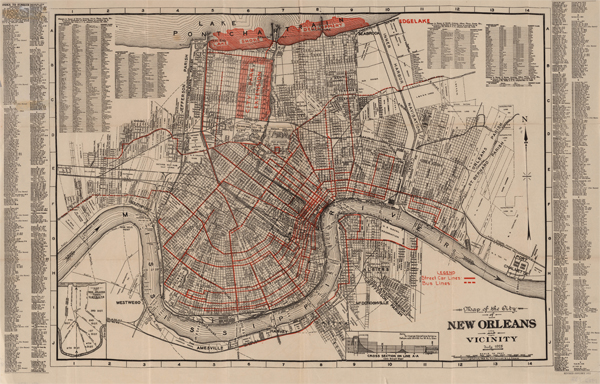

That’s a great geohistorical distinction. When Louisiana was sold to the United States by Napoleon Bonaparte at the end of 1803, there was no Protestant church in New Orleans, and no Catholic church in Boston, where “papists” had long been persecuted. As the Anglo-Americans moved down to Louisiana, the two great cultural regions of the hemisphere—Catholic, reaching down to Brazil and beyond, versus Protestant, reaching up to New England and English Canada—had their frontier precisely at the neutral ground that was later called Canal Street. When we talk about Congo Square, as sooner or later we do, we understand we’re talking about Catholic downtown, “below” Canal Street. The Bakongo people — generically called “Congo” or “Angola” by slave traders — who came in some numbers to Louisiana during the Spanish colonial years, were understood to be Catholic.

The African kingdom of Kongo was Catholicized in 1491 — yes, before Columbus — when the manikongo (Kongo king) Nzinga a Nkuwu enthusiastically accepted baptism as King João I, with massive conversion imposed on the vast Kongo kingdom by his son. This brought to Kongo’s ancient set of spiritual practices and long-existing cosmology a new set of hierarchies, symbols, performativities, and power objects that fit more or less well with what already existed. In other words, the much-discussed syncretism of traditional African spiritual practice and Christianity happened in Kongo before the Middle Passage, and was transmitted from Africa to all parts of the Americas, providing a far-reaching cultural unity.

In Kongo thought, there are two worlds in constant contact: the land of the living and the land of the dead, which are separated by a water barrier called kalunga. Think of all those spirituals and blues tunes about the other side of the river: the Mississippi was kalunga. When kidnap victims made the hellish voyage to the death-in-life of slavery, the Atlantic was kalunga. And when it rains like it rains in New Orleans, and Canal Street becomes a watery barrier, it too might be kalunga. In the days of French versus English speakers, Canal Street was a boundary, above which it was harder to call the ancestors, because the Anglos prohibited the hand drum.

Kongo spirituality fit into Catholic New Orleans for the same reason that the Bakongo people were under a cloud of suspicion as fifth-columnists throughout the Anglo-American world: unlike Senegambians (whose culture was Islamized) or Dahomeyans (understood to be “pagans”), it was understood that Central Africans (Bakongo, Mbundu, and others) were Catholic, and in colonial Anglo-America, Catholics were the enemy. The largest slave rebellion in colonial Anglo-American history, the Stono rebellion of 1739, was explicitly Protestant versus Catholic: a group of “Angola Negroes” imprisoned on plantations in South Carolina rose up in an attempt to take the governor of Spanish Florida up on his offer of freedom and land for those professing the true faith. But although Central Africans were considered potential Catholic terrorists in Carolina and Virginia, in New Orleans, as in Havana, the Bakongo had access to the city’s religion, and they made use of it in all kinds of ways – I have only to mention Marie Laveau, the voodoo queen, a free child of the Spanish regime. Haitian-style vodou, which has a long history in New Orleans, has a significant Kongo influence.

Congo Square was across from the French Quarter; it would have been unthinkable in the Anglo-American sector above Canal Street. The Congo Square gatherings were not only an assertion of resistance by the enslaved; they were also a marker of Creole-Catholic slaveholders’ resistance to domination by Anglo-Protestants, whose way of repressing Black culture was much different from theirs.

Bruce Raeburn, longtime director of Tulane University’s Hogan Jazz Archive, has referred to Congo Square as a “regulatory period.” As New Orleans Americanized, the drumming and dancing could perhaps not be stopped, but it could be restricted to a single time and place, there to be watched, policed, and cut off none too politely at the appointed hour – not unlike Sunday second lines in the 21st century. In the early days of the gatherings at Congo Square, the goings-on would not have seemed particularly remarkable in Cuba or in Saint-Domingue, where, unlike in the Anglo-American world, Africans continued (and their descendants still continue) to play ancestral drums, sing in ancestral languages, dance ancestral dances, and worship ancestral deities.

But over time, styles change. If there were Bakongo at Congo Square, or vodouisants from St. Domingue, communicating across the kalunga line with their drums, that’s not all that was going on. As traffic from Africa shut off, and the United States slave-breeding industry developed, during Louisiana’s boom years, the slave ships came to New Orleans not from Africa but from Alexandria, Richmond, Norfolk, Baltimore, Charleston . . . and the groups who came together in the circles of Congo Square were increasingly inventing a new, African American musical language. In that new language, which we surely hear traces of in the present-day music of the Mardi Gras Indians, there still remained an awareness of a city constructed in sectors. Every year, when the Indians have their annual Super Sunday event, there are two versions: uptown and downtown, marking the moieties of New Orleans.

Ned Sublette is the author of four books: The American Slave Coast (with Constance Sublette), The Year Before the Flood, The World That Made New Orleans, and Cuba and Its Music. He founded the production company Postmambo Studies and co-founded the record label Qbadisc. He has produced over one hundred one-hour radio documentaries for the public radio program Afropop Worldwide and co-founded their scholarly Hip Deep subseries. He lives in New York City.