Top of the Boot

Louisiana’s original state line

Published: September 1, 2020

Last Updated: November 30, 2020

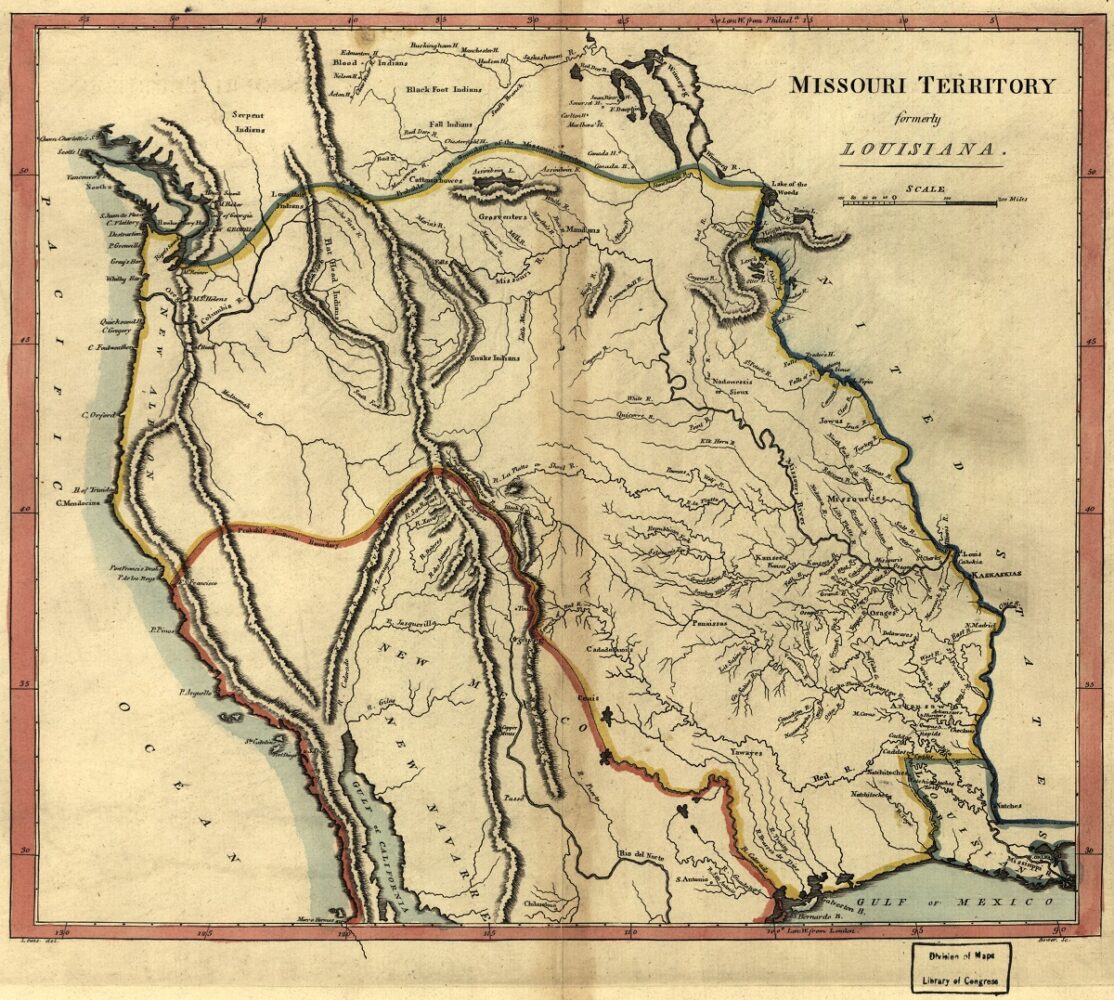

Library of Congress

1814 map of the Missouri Territory by Matthew Carey, featuring ambitious boundaries for the incompletely described territory.

Parties agreed that the Mississippi River formed the eastern edge of the transaction, and that the Continental Divide—whenever it might someday be mapped—would form the western edge. But no one quite understood where ran the northern and southern edges, abutting British and Spanish possessions; ergo no one knew the full expanse of the real estate deal—perhaps 830,000 square miles, give or take a few thousand.

The sudden doubling of national territory called for some new political geography. On March 26, 1804, the US Congress in Washington, DC, approved “An Act erecting Louisiana into two territories, and providing for the temporary government thereof.” The opening section enacted “that all that portion of country ceded by France to the United States, under the name of Louisiana, which lies south . . . of an east and west line to commence on the Mississippi river, at the thirty-third degree of north latitude, and to extend west to the western boundary of the said cession, shall constitute a territory of the United States, under the name of the territory of Orleans” (italics added).

Subsequent sections created the positions of governor and secretary, legislative and judicial bodies, as well as basic territorial laws. A later section decreed that the “residue of the province of Louisiana,” meaning those lands north of the 33rd parallel, “shall be called the district of Louisiana,” and went on to establish its governance.

In this decree, the 33rd parallel went from the theoretical graticule of cartographers to the official map of the United States, as a separation of the Territory of Orleans (or Orleans Territory, with its headquarters in New Orleans) from the District of Louisiana (later renamed the Territory of Louisiana, or Louisiana Territory, headquartered in St. Louis). As initially described, the border ran over 280 miles, from the Mississippi River in present-day East Carroll Parish to the upper Sabine River in what is now rural northeastern Texas, east of Dallas.

Why the 33rd parallel? Though members of Congress debated seemingly every conceivable aspect of the Louisiana Purchase, I could not find any recorded discussions specifically on the selection of the 33rd parallel as a territorial border. Perhaps a consensus formed that this convenient round-integer latitude was as good as any arbitrary line. It lay roughly halfway between New Orleans and St. Louis, the two key Mississippi River cities within the Purchase, and did a decent job of separating out the more heavily populated and economically vital lower-Louisiana region from the vast unchartered wilderness to the north and west.

The US government in this era was also somewhat wary of its new citizens—they being French in tongue, Catholic in faith, Creole in ethnicity, and monarchical in their political legacy—to the point that the territorial government it created for them was initially appointed, not elected. The 33rd parallel fairly well separated out those predominately Creole populations to the south from the hinterlands to the north and west, where presumably Anglo-American emigrants comprised the majority of non-indigenous residents. It’s also worth noting that the 33rd parallel roughly demarcates the maritime-dominated subtropical climate to the south, with its longer growing season, from the more frigid continental climate of the interior, and thus had agricultural significance. Whatever the motivations, the 1804 delineation decision would make a permanent mark on the American map.

Over the next eight years, the territorial government carved out a confusing dual system of counties and parishes throughout the Territory of Orleans, the former for electoral and taxation purposes, the latter for judicial matters. The 33rd parallel thus became embedded into the borders of the counties/parishes of Natchitoches and Ouachita, which in time would be subdivided to add our present-day parishes of Caddo, Bossier, Webster, Claiborne, Lincoln, Union, Morehouse, and West and East Carroll. (Mercifully, counties were eliminated from official Louisiana geography in the 1840s).

As for the part of the Territory of Orleans extending westward into Texas, that wedge of land got clipped off in an arrangement with Spain to resolve a border dispute leftover from the Louisiana Purchase. On February 20, 1811, Congress enacted a law allowing residents of the Territory of Orleans to form a state government and constitution toward admission into the Union. That act described the forthcoming State of Louisiana’s western and northern boundary as “Beginning at the mouth of the River Sabine, thence [northward] along the middle of the [Sabine] to the thirty-second degree of north latitude, thence due north to . . . the thirty-third degree of north latitude, thence along [that] parallel . . . to the River Mississippi, thence down to said river” toward the sea (italics added).

In 1812, the Territory of Orleans became the State of Louisiana; the Territory of Louisiana got renamed the Missouri Territory; and the 33rd parallel became Louisiana’s first undisputed straight border segment.

The section of that 1811 law invoking the 32nd-to-33rd parallel is today’s rectitudinous north–south state line west of Shreveport. But at the time, this vicinity remained a disputed region with Spain. As part of the same Adams–Onís Treaty that, in 1819, transferred Spanish West Florida and the Sabine Free State to the United States, the Americans ceded lands along its far-western frontier to Spain, among them that wedge-shaped western tier of the former Territory of Orleans that poked into present-day Texas.

For two years, Louisiana’s only ninety-degree angle became, along its lower leg, a Spanish–American border. In 1821, with the independence of Mexico, it became a Mexican–Louisianan border, and fifteen years after that, it became the Texas–Louisiana border—in the same year (1836) that Arkansas entered the Union, thus forever cementing the 33rd parallel as the Louisiana–Arkansas state border.

It would be the sole use of the 33rd parallel in the shape of any American state—and a distinctive one at that: top of the boot.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans: A Historical Geography (LSU Press, 2020), Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.