Geographer's Space

Putting the “64” in 64 Parishes

A geographical self-assessment

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: August 30, 2019

Maps by Richard Campanella

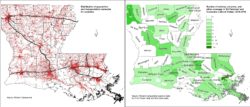

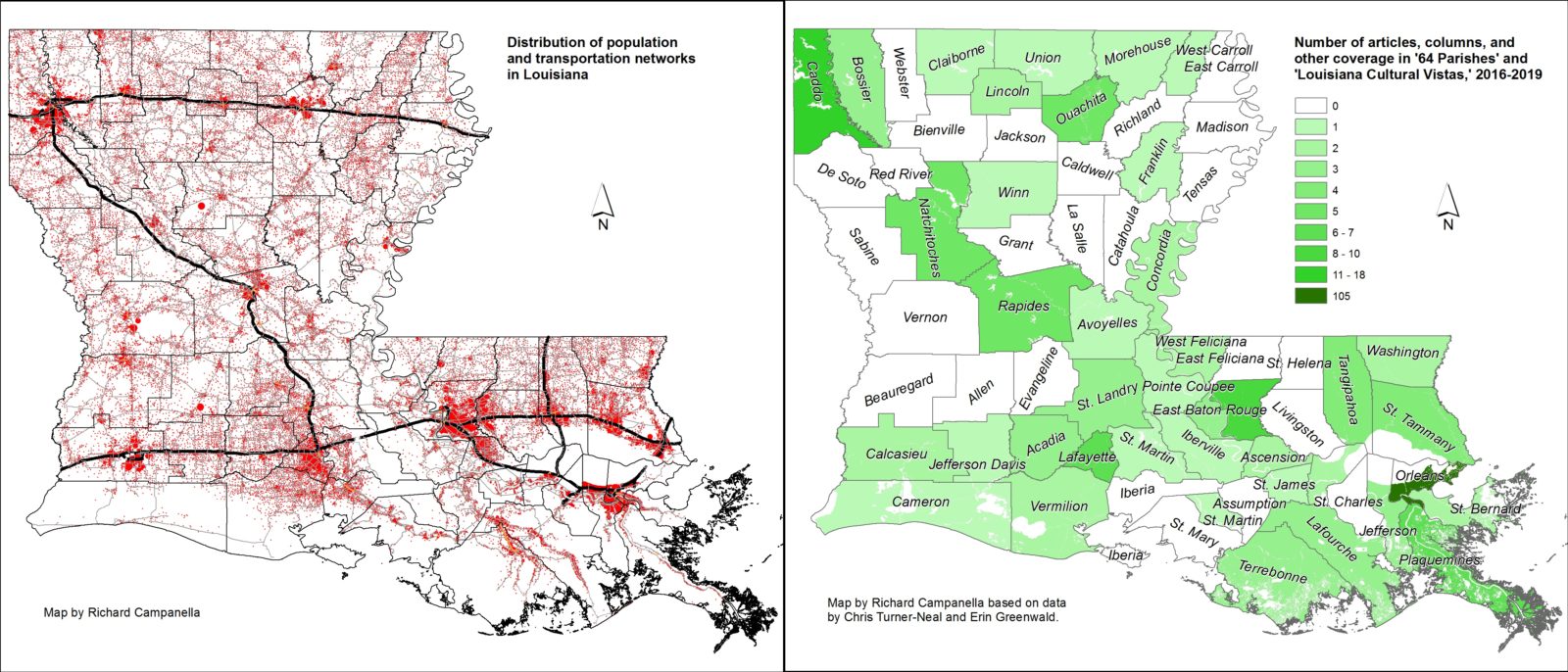

Maps showing distribution of population and transportation networks in Louisiana (left) and number of articles, columns, and other coverage in Louisiana Cultural Vistas and 64 Parishes by parish, 2016–2019 (right)

The geographer in me was intrigued. Part of me welcomed the overdue attention to be paid to some of the state’s more rural parishes and lesser-known peoples, places, and folkways. The other part recognized that humans are not evenly distributed around the state; they cluster in cities of various sizes, which themselves are unevenly dispersed. We therefore should not expect as many humanities stories to come out of, say, Tensas Parish (population 4,615, the lowest) as East Baton Rouge Parish (highest, at 446,268), or from Orleans Parish, now the third-largest parish but for centuries home to Louisiana’s largest city, New Orleans, and a major engine room for cultural production.

Then there is the factor of authorship. The LEH is based in New Orleans, as are many contributors, including yours truly. Others typically come from the state’s larger cities and/or academic institutions. We’re not reporters given assignments by the editors; rather, we’re contributors who are paid modest stipends for our submissions, and we naturally draw from our areas of expertise when we select our topics and write our stories. Those topics tend to have a certain constellated geography—and they tend not to be in the Tensas Parishes of the state.

So I wondered exactly what sort of statewide coverage the magazine had been exhibiting all along. Apparently, so did the LEH. Earlier this year, 64 Parishes Editor-in-Chief Erin Greenwald called for an internal review of the magazine’s parish-level coverage, going back to 2016, when it was still called Louisiana Cultural Vistas. According to an email sent to me from Greenwald, Managing Editor Chris Turner-Neal “went through the issues . . . manually, tallying up [by parish] every piece in each issue that fell into each of the following categories: Parish Spotlight, Column, Feature, Photo Essay, [and] Partner Content. In order for an article to reach the threshold of ‘this article is about x parish,’ there had to be substantive content tied to the parish, not just a name drop.” Greenwald and Turner-Neal are to be commended for this institutional self-assessment, and I appreciate that they agreed to my request to analyze the data for this column.

The results?

As expected, the spatial distribution of humanities coverage fairly well matched the spatial distribution of humans. More people, bigger cities, more content, more coverage: that makes sense, and that’s OK.

What was problematic was the disproportionality. Some big parishes got a whole lot of coverage, while many small ones got none. Of the 221 pieces tabulated by Turner-Neal, fully 48 percent were about Orleans Parish, which makes up only 8 percent of the state’s population (22 percent if we consider metro New Orleans). Twenty-five parishes got zero explicit coverage, though most got some regional attention even if their names were not specifically mentioned.

Then there were parishes that got fair coverage in an absolute sense, but less so in a relative sense. For example, Jefferson Parish had three pieces over three years, which was the statewide per-parish average. But given that Jefferson is the second-most-populous parish, its per-capita coverage was among the lowest: one piece for every 144,000 people. Cameron, on the other hand, got only one piece, but being among the least populated parishes, that’s one piece for every 6,800 people.

At least three parishes were spot-on, having a statewide-average number of pieces that was also proportional to their population. Interestingly, all three were Acadiana parishes: Acadia, St. Landry, and Terrebonne. Why? Perhaps because humanists tend to find lots of content in Cajun and Creole cultures (food, music, festivals), despite their small populations. A number of comparably sized parishes in the upper-delta country and along the Sabine River, on the other hand, got no coverage. This broaches provocative questions of exactly what (and who, and where) makes for worthy humanities content.

Some other trends and patterns:

“Parish Spotlight” pieces tended to have a strong urban-centric distribution, possibly because the events and exhibits featured in these call-outs are more likely to take place in cities.

This was also the case for “Partner Content,” likely because partners, including foundations, institutions, and corporations, tend to be based in metro areas and missioned to serve those populations.

“Columns” were highly New Orleans-centric, with 27 of 44 about Orleans Parish, and all other parishes getting no more than two. The main factor here is probably the preponderance of New Orleans–based columnists with New Orleans-centered expertise.

“Feature” stories were also New Orleans-dominant, 22 out of 41, and overall there was a southern predomination, with more coverage of the Acadiana and/or coastal parishes than the northern part of the state. Over 86 percent of feature stories, which often end up on the cover, were south of the 31st parallel, an area that contains a little more than half of all parishes.

Unsurprisingly, the 25 zero-coverage parishes tended to be the most rural, least urbanized, and farthest from major interstates and highways. They tended to cluster in the central and northern part of the state. The Sabine River Valley parishes, namely DeSoto, Sabine, Vernon, and Beauregard, formed the biggest contiguous blind spot, followed by the upper-delta parishes in the northeastern corner.

There were also some surprises. Livingston Parish, home to over 138,000 people and located between two university cities (Baton Rouge and Hammond), got no coverage, nor did St. Charles Parish, despite having lots of river history and coastal stories as well as a semi-urbanized population of over 52,000. Among the larger cities, Lake Charles got unusually light coverage.

I wondered about my own geographical coverage over the six years I’ve been writing “Geographer’s Space.” For the record, I am a New Orleans geographer, based at Tulane University, and I live in New Orleans. Of the twenty-four columns I’ve written in the past six years, 54 percent have been on statewide topics or transcending phenomena such as Louisiana topography or the Mississippi River; over 20 percent have been about New Orleans; 13 percent the coastal region; and another 13 percent on other Louisiana cities, namely Gretna, Baton Rouge, and Alexandria. So I, too, could use a nudge to expand my horizons.

If I were to draw certain recommendations from these data, I might suggest prioritizing stories in those zero-coverage parishes that have the largest populations and/or the most contiguous juxtapositions. This might entail featuring communities like Leesville, DeRidder, and Tallulah, or proactively seeking researchers and photographers from the central and northern Louisiana countryside. It’s commendable that the LEH is increasingly holding its semi-annual issue-release parties all over the state, a great way to get the humanities in front of new folks while having some fun in the process.

It might be asking too much for 64 Parishes to cover all parishes with equalized weight. But it would be a noble goal to make the coverage commensurate to the population distributions of the 64 parishes—none of which, of course, has zero people.

Editor’s note: This issue’s piece by Chere Coen explored the historic and ostensibly haunted jail in DeRidder (Beauregard Parish). Look for fall coverage on Louisiana’s first female African-American doctor, a New Iberia native (Iberia Parish), as well as cochon de lait traditions maintained outside Tallulah (Madison Parish). Parish by parish, we’re coloring in the map.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, Bourbon Street: A History, and other books. He may be reached at richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Check out the Geographer’s Space video series online at 64parishes.org.