Henry Adams

Henry Adams was a former enslaved person who spearheaded North Louisiana’s first civil rights campaign for African Americans.

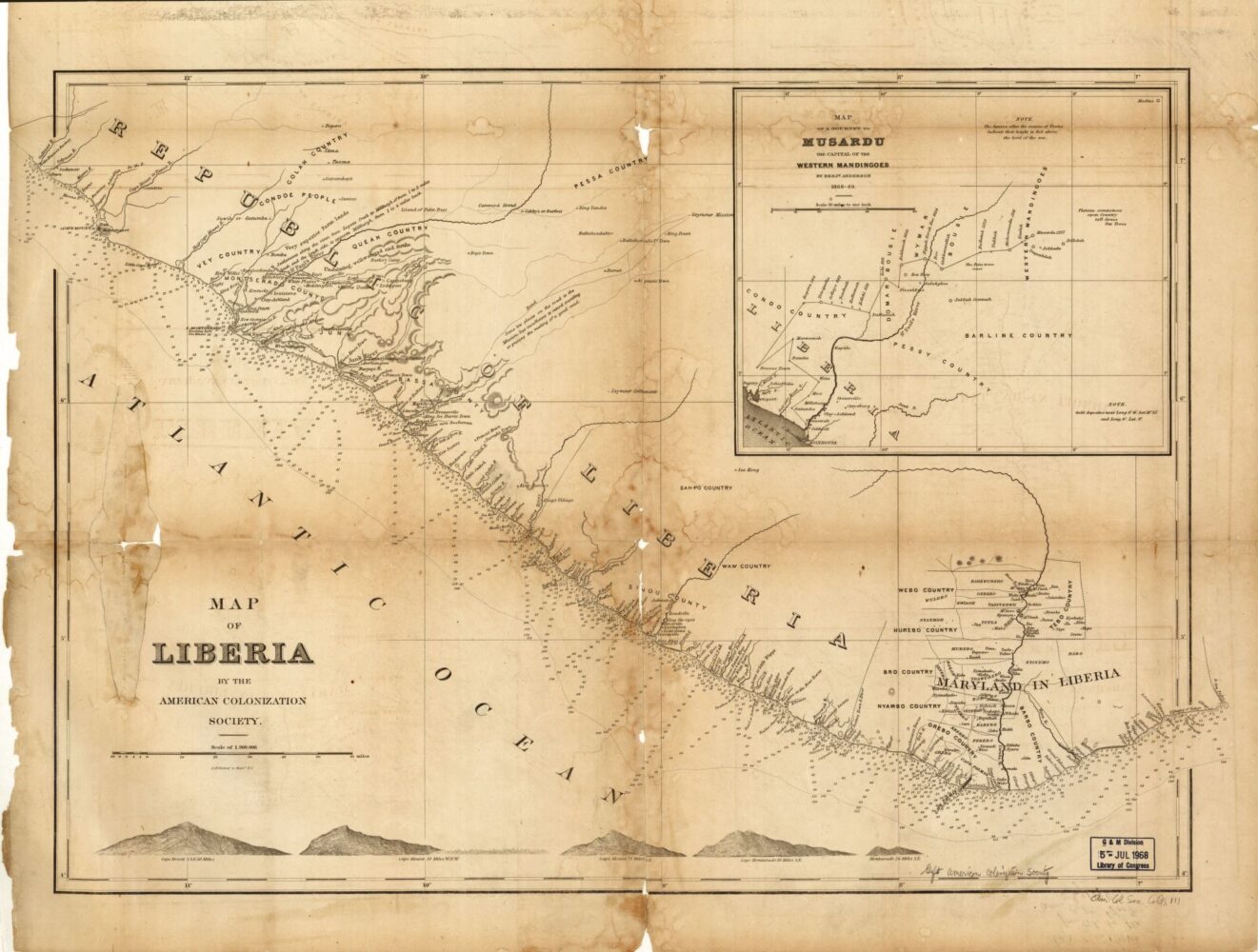

American Colonization Society, Library of Congress

Late in his life, Adams was involved in the project to send African Americans to colonize Liberia, and may himself have left for West Africa.

A former enslaved person, Henry Adams (1843–unknown) spent much of his adult life in and around Shreveport, spearheading what could be considered the region’s first civil rights campaign. He promoted full voting rights for freedmen in the years after emancipation, then encouraged the migration of African Americans from the South to more welcoming locations following the end of Reconstruction.

Early Life and Freedom

Adams was born into slavery in Georgia in 1843 and was brought to Louisiana before the Civil War when his owner, whose name was Adams, moved his entire estate to DeSoto Parish in 1850. When Adams’s owner died in 1858, he left his plantation and sixty enslaved people to his daughter, Nancy Emily Adams, who freed them on May 26, 1865, the day Shreveport surrendered to Union forces.

Newly free, Adams, then 22, made his way to nearby Shreveport with his wife, Malinda; the couple eventually would have four children. Adams became a drayman, obtaining a horse-drawn cart and operating his own hauling business. But soon he grew angry with the feeling of helplessness that so many formerly enslaved people experienced at the end of the war. The political climate was miserable. The state government was controlled by African Americans but was also to a considerable degree manipulated by Radical Republicans in Washington, one of whose aims was to humiliate white ex-Confederates. The Freedman’s Bureau established by Congress to help formerly enslaved people was underfunded, and some unionist politicians, known by the derisive terms “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags,” claimed to be allies to African Americans but often betrayed them. Ex-Confederates promoted secret societies aimed at regaining white control of the state government. White supremacists instigated riots, lynchings, and other criminal forms of civil disorder, invariably blaming their victims for causing the trouble. Typically, they went unpunished.

Frustrated by this state of affairs and determined to make a difference, Adams left his draying business and joined the US Army in September 1866. By the time of his discharge in 1869, Adams had attained the rank of quartermaster sergeant and had learned to read and write. Returning to Shreveport from the New Orleans area, he was dismayed to find that conditions for African Americans had not improved but, on the contrary, worsened in his absence. Going to work as a woodcutter and plantation manager, Adams earned a decent living and was much in demand. He worked for some of the area’s most prominent planters, including ex-slaveholder Col. J. M. Foster.

Campaigns and Activism

In 1870 Adams gathered a group of freedmen to investigate the conditions of formerly enslaved people in the region. Some 150 members canvassed the South from Virginia and to Louisiana creating detailed reports on working conditions, pay, grievances for injustices done to them or their families, attacks by the Ku Klux Klan or other white terrorist groups, and harassment at the ballot box. “The Committee,” as it was called, found that living conditions among people of African descent varied widely, but for most, the lot of formerly enslaved people was bleak.

By 1874 the Committee had more than 500 members. The membership determined that improvement of conditions was virtually impossible and that exodus was the only solution left to them. In September 1874, the Committee became “The Colonization Council.” It operated as a secret fraternal society and within a year had attracted 98,000 members, mostly from North Louisiana, east Texas, southern Arkansas, and sections of Mississippi and Alabama. The primary objective of the Colonization Council was to improve the conditions of African Americans in the South. Failing that, it sought to petition the President of the United States for the genuine protection of Black citizens, then to request a block of territory upon which a Black majority state could be founded, and finally, as a last resort, to leave the country.

In testimony before a US Senate special committee investigating the “Negro Exodus from the Southern States” in 1880, Adams described the origin of the late-nineteenth-century civil rights movement: “Well, along in August sometime in 1874, after the White League sprung up, they organized and said this a white man’s government, and the colored men should not hold any offices; they were no good but to work in the fields and take what they would give them and vote the Democratic ticket. That’s what they would make public speeches and say to us, and we would hear them. We then organized an organization called the colonization council.”

Actively campaigning for improved conditions for African Americans, Adams lost many friends in the white community, and his livelihood suffered as he became welcome on fewer and fewer plantations. Secret meetings of the council grew so large that they often ceased to be secret; one 1878 meeting in Shreveport drew 5,000 people. Finally, in December 1878, fearing for his life, Adams and his wife and child left Shreveport for New Orleans, never to return. The Council remained active, however, and Adams continued to be its driving force.

Kansas Exodus and Final Years

In 1879 and 1880 Adams led a movement to establish a Black colony in Kansas. Some 30,000 “Exodusters,” as they were called, made the migration. The effort was publicly opposed by Frederick Douglass, the foremost national African American leader of the day, who urged besieged freedmen to stand their ground in the South and fight for improvements there rather than giving in to the terror and discrimination they encountered. “We cannot but regard the present agitation of an African Exodus from the South as ill timed, and in some respects hurtful,” Douglass wrote at the time. “We stand today at the beginning of a grand and beneficent reaction. There is growing recognition of the duty and obligation of the American people to guard, protect, and defend the personal and political rights of all the people of the States. … At a time like this, so full of hope and courage, it is unfortunate that a cry of despair should be raised in behalf of the colored people of the South.”

The Kansas Exodus failed to gain national support, and many of the Exodusters struggled to achieve long-term success when faced with the agricultural challenges of available lands. With the disappointing results of the Kansas Exodus, Adams turned his sights to Liberia, a West African colony founded by the American Colonization Society in 1824 as a relocation settlement for free-born and formerly enslaved African Americans. However, the Liberia idea produced limited enthusiasm. By 1884 the activities of the Colonization Council had largely come to an end and Adams disappeared from the public eye. In the next quarter-century, more than 11,000 African Americans left the South for Liberia; it was never determined if Adams and his family were among them.