Louisa Lamotte

A Creole of color who became a pioneering scholar of education in France

Courtesy of Private Collection

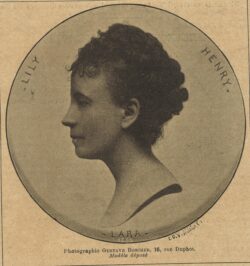

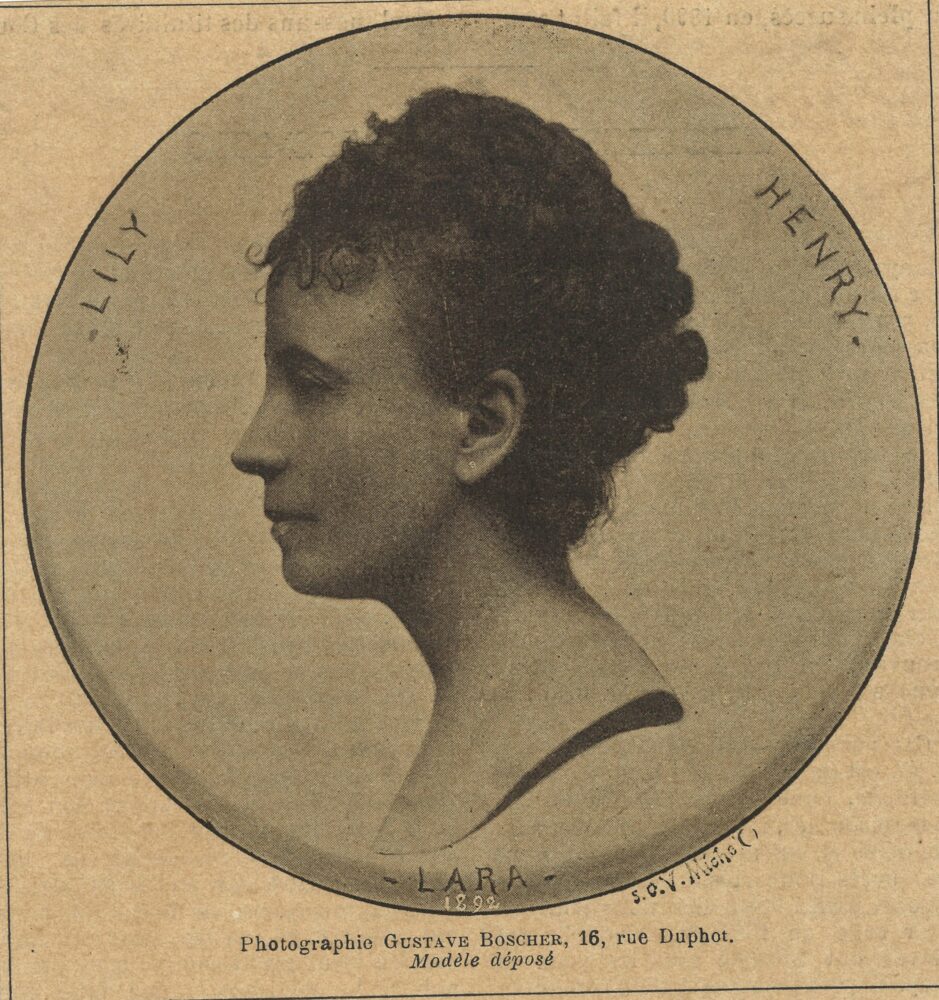

Portrait of Louisa Lamotte. Gustave Bocher in La Pleiade

Louisa Lamotte was a New Orleans–born Creole of color who was educated in Paris, where she became a pioneering educator, scholar, and important publisher of pedagogical material. As a creative writer, Lamotte authored numerous children’s stories, but she often concealed her identity with a variety of pseudonyms. Thus, the full extent of her literary production may never be fully acknowledged. Lamotte received France’s highest academic honor when she was named to the Ordre des Palmes Académiques in 1899, becoming one of the first American educators and the first woman of color to receive this award. She returned briefly to New Orleans in 1894 to appear before the Louisiana Supreme Court in a case concerning her father’s estate. The stress of subsequent trips to the Crescent City to deal with her father’s legal entanglements seem to have exhausted her and she died there on January 9, 1907.

Early Years and Education

Louisa Lamotte was born in New Orleans on January 11, 1848, the daughter of Rosa Emma Dupuis and André Martin Lamotte, who married in 1838. Lamotte’s mother descended from a well-respected family of Creoles of color and left her daughter property in the Faubourg Marigny on Rue Victoire, an area heavily settled by Saint-Domingue refugees beginning in 1809. Lamotte’s father, born in 1818 in New Orleans to a white aint-Dominguan father and a free woman of color, became a well-known builder and constructed many of the Creole cottages that give the Marigny its distinctive character. Lamotte’s parents seem not to have registered her birth in New Orleans, perhaps to shield her from the ever-increasing racism that was prevalent in the South in the years before the Civil War. Shortly after her birth, Lamotte traveled with her parents to Paris where attitudes about race, if not free of bias, were less oppressive than in the antebellum South. When Lamotte’s mother died soon after their arrival, her father paid for the child’s care and schooling in the French capital. She earned her first professional credentials in 1863 at the age of 15 and went on to receive her teaching certification, earned the equivalent of two masters degrees, and developed specialties in pedagogy and school administration. Lamotte’s accomplishments are significant when considering that the first Frenchwoman to have completed the baccalauréat, or national secondary exam, was in 1861, ten years before Lamotte completed her licence ès lettres at the university level. In the United States, Mary Jane Patterson, a woman of color, graduated from Oberlin College in 1862.

The Educator and Her Philosophy of Teaching

Lamotte is most associated with her important role in women’s education. In 1871, when women had limited access to public instruction, Lamotte acted on then-radical ideas that education should be free, secular, and universal and began teaching free evening courses to 96 girls during the Paris Commune. Shortly after the collapse of the short-lived revolutionary government, she married a French merchant, François Joseph Hippolyte Rouilliot, on November 13, 1871, and lived briefly in Troyes. By 1873 she separated from her husband—divorce was illegal at this time—and returned with her daughter Marguerite to Paris where they resided at 2 rue des Batignolles. Soon thereafter, Lamotte published one of the earliest scholarly works on the history of women’s education in France, De l’enseignement secondaire des filles, published in 1880, the same year that the French government mandated secondary education for girls. During the same period, Lamotte authored numerous articles in the Revue pédagogique and, in 1883, became the director of Collège de Jeunes Filles in Abbeville, France. By 1884 she had penned a manifesto in which she proclaimed: “Knowledge … must not remain the arbitrary monopoly and exclusive domain of a single sex, and within that group, of a single category of individuals. It is henceforth the property of all: the duty of the state is to facilitate free access to it.” Despite her high level of education, Lamotte had an exaggerated dress and “languid air” that played into common nineteenth-century century stereotypes and discredited her critique against the church’s responsibility for women’s education. A New Orleans Creole and a single mother who failed to conform to social expectations, she was hypersexualized as a woman of color and considered unfit to teach innocent French girls. When a newspaper story appeared accusing Lamotte of an irregular relationship with the mayor, her career in public education was effectively over, despite no official charge of wrongdoing. Beginning in 1886 she established a series of private schools in the French capital and devoted her time to publishing.

Author and Publisher

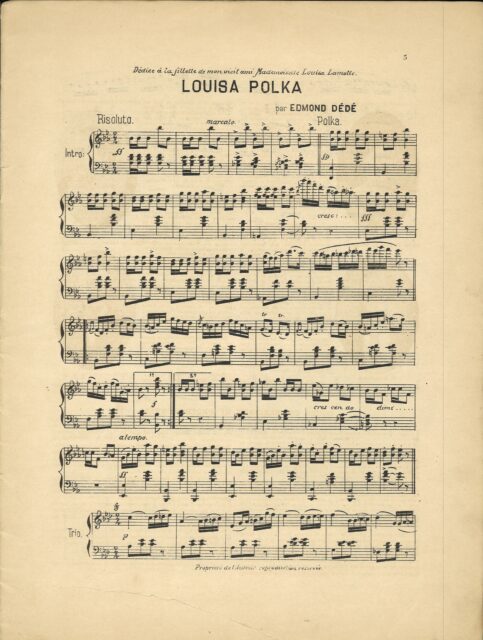

When Lamotte boarded the USS New York bound for the United States in 1894, she listed her profession on the ship’s register as “publisher” rather than as a school administrator or teacher. She was referring perhaps to her magazine La Pléïade: Revue littéraire, musicale et artistique, which appeared annually between 1892 and 1894 and which contained early piano compositions by several Black American composers. (Lamotte was well known to the Creole composers who had settled in Paris before the Civil War—Edmond Dédé, Eugène Dédé, and Lucien Lambert were all old family friends, and all dedicated compositions to her.) The magazine contained ample contributions by contemporary poets, composers, dramatists, and illustrators as well as favorable reviews of the many concerts and literary events sponsored by the publication. It served as a sort of literary “salon” for progressive Parisians.

Édmond Dédé, “Louisa Polka, dédié à la fillette de mon vieil ami, Mademoiselle Louisa Lamotte,” La Pléïade: Revue littéraire, musicale, et artistique, 1892-1893, 5-6, (collection of the author).

Lamotte’s self-identification as a publisher is most likely a reference to her association with Éditions Charles Delagrave, arguably the most important publisher of pedagogical material in nineteenth-century France. Between 1875 and 1895 Lamotte published nearly twenty books, scholarly articles, and short stories with the firm’s Delagrave imprint under her own name. As a comparison, her illustrated short fiction in the children’s magazine Saint-Nicolas: journal illustré pour garçons et filles appeared a decade before Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s Violets and Other Tales, published in 1895. The subject matter and intended audience of these two authors’ stories differ enormously. While Dunbar-Nelson wrote for a sophisticated public that appreciated a finely crafted tale, Lamotte created a literature for children whose goal was to educate young girls and boys so that all would be equally prepared to create lives that reflected the republic’s values of liberty, equality, and fraternity. In doing so, Lamotte left behind one of the earliest bodies of fiction by an American woman of color.

That Lamotte used aliases is beyond question; she herself revealed two of them in her magazine La Pléïade—Lara and Lily Henri. However, as a self-proclaimed “publisher” with a long history with Delagrave, it is likely that she is one of many individuals behind the house pseudonym “Eudoxie Dupuis” and the hundreds of Delagrave publications that bear that name. Dupuis is the family name of Lamotte’s mother, and “La Princesse Eudoxie” is a main character in La Juive, an opera written by Fromental Halévy with a libretto by Eugène Scribe in 1835 (the date frequently given as the year of Eudoxie Dupuis’s birth). The story tells the impossible love between a Christian man and a Jewish woman, and Lamotte would have certainly noted the parallels of religious intolerance central to her own position in postbellum America. Furthermore, Dupuis’s death date is sometimes given as 1907, the same year Lamotte passed away. Delagrave seems to have retired the name upon Lamotte’s death, and it is because of the firm’s extensive use of house pseudonyms that literary historians will unlikely establish a definitive catalog of works attributable to Louisa Lamotte.