Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle

The Economy and Mutual Aid Association was a New Orleans-based benevolent organization of African descendants that exerted international reach and significant cultural influence.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

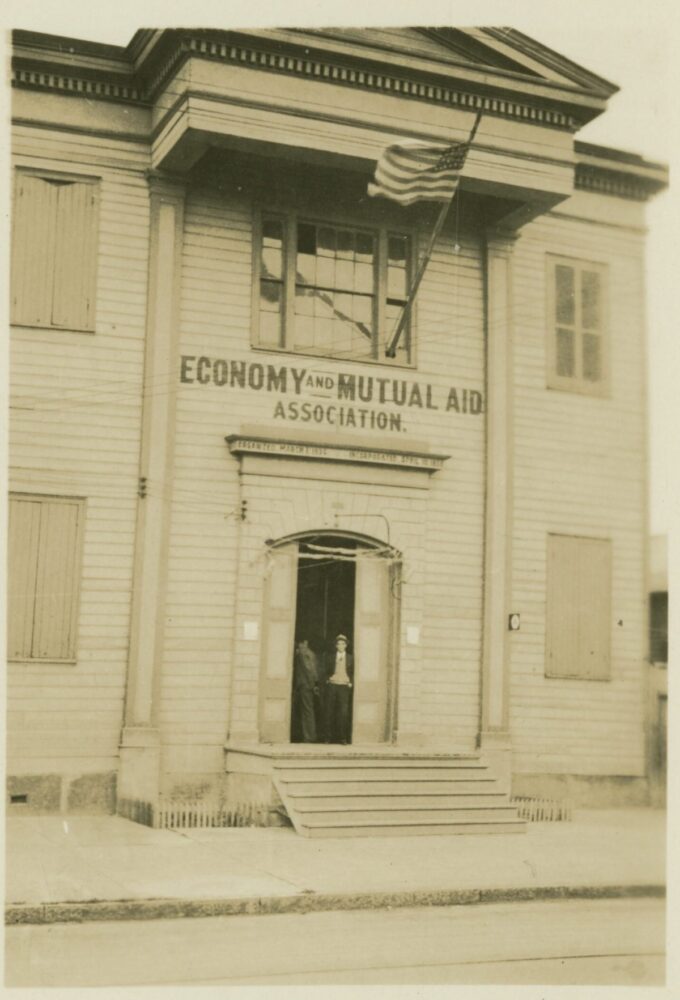

An exterior view of Economy Hall.

The Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle (the Economy and Mutual Aid Association) was a multi-ethnic benevolent organization formed by men of African descent based in New Orleans. The society was uniquely defined by its international reach, antebellum wealth, cultural influence, and longevity.

Founded in 1836 the 15 original members of the Economie were French speakers with ancestral roots in Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and Central America. From the creation of the organization to its demise in the early 1950s, the men of the Economie were characterized locally as Creoles due to their language and cultural traditions—the hybrid of African, Indigenous, and European foodways and family practices—or ancestry dating from French and Spanish colonial Louisiana. The US census and newspapers designated them racially as coloreds, Negroes, and blacks.

As a mutual aid organization, the Economie required members to pay dues at every meeting into a cash reserve for financial support of one another’s families in times of sickness and death. The Economie also provided a social network for members’ entrepreneurial efforts. In 1836, when membership initiation cost $25, the men pooled their money to purchase a small house at 219 Ursuline Street in New Orleans to house their library, archives, and meeting rooms. The Economie regularly took up collections to support the indigent, individuals, and local charity institutions, universities, and hospitals. In 1841 the Economie gave $369 in profits from a ball to charity, which was then the equivalent of three years’ wages for the average worker.

The wealth and literacy of the first Economie members came from inheritances, military service, and real estate. Economie members were traders, contractors, craftsmen, and teachers. Ludger Boguille operated a private school in 1840, joined the Economie in 1852, and by his admission in Harper’s Magazine and the New Orleans Tribune taught free children and the enslaved—which was against the law. Later members earned from their successful businesses like Pierre Casanave, a mortician known for innovations in embalming.

Before the Civil War the Economie maintained ties to Haiti, France, and Mexico, places from which their families and others in their Creole community had immigrated. Members traveled to their relatives and businesses abroad despite laws intended to limit the movements of Black people in the South. The society remained ideologically tied to Saint-Domingue following the Haitian Revolution, a time when Western nations and the US South vilified the newly independent nation of Haiti. In 1838 the Economie conducted a ceremony honoring Alexandre Pétion, the first president of the Haitian Republic. A ceremony took place in the Economie’s small meeting house to receive a portrait of Pétion from the estate of Charles Laveau (father of Marie Laveau), whose home had hosted the Economie’s first meeting. Members Joseph Firmin Perrault and Myrtil Piron immigrated to and returned from Haiti with their families.

The society’s antebellum internationalism is reflected in its members’ activities. Etienne Cordeviolle and François Lacroix operated tailoring businesses in Paris and New Orleans as early as the 1840s. Prospère Avril, Louis Nelson Fouche, Constantin Deburque traveled in and out of Mexico in the 1850s. In 1857 the members received a portrait of Mexican president Ignacio Comonfort, who invited them to immigrate as the possibility of Black citizenship had been rebuffed by the US Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision. Some members moved while others stayed in the United States and continued to work for political and social equity.

In the early 1860s, when the future was uncertain for Louisiana’s population of African descent, the members of the Economie took the lead in providing a venue and forums to shape an integrated body of voters. On June 30, 1863, a French-language gathering of African descended men gathered in the group’s headquarters to advocate for full American citizenship. A few months later, on November 5, 1863, members of the Economie held a meeting to discuss suffrage of “six or seven hundred people,” according to the New York Times, “unquestionably one of the most important and significant meetings which have ever taken place in this city.” Member François Boisdoré, the son of a Battle of New Orleans veteran said, “When our fathers fought in 1815, they were told that they should be compensated; we have waited already a long time for it …We have waited long enough.” In September 1865 economist Ludger Boguille sat inside Economy Hall during a voter registration drive held by the Friends of Universal Suffrage to show the numerical strength and interest of Black voters. On September 25, 1865, the Friends of Universal Suffrage met in Economy Hall with the National Union Republican Club and others to form the Louisiana Republican Party. In 1868, white supremacists attempted to burn the Economy Hall and succeeded in destroying registration books and furniture.

The balls and concerts sponsored by the Economie are cultural legends. The organization built a grand hall at 1422-26 Ursulines Avenue in the Tremé area in 1857 that stood until 1963. The opening of the la Salle d’Economie, or Economy Hall, brought together the Société Philharmonique, a group of musicians of color, among them founder and violinist Charles Martinez. More than 100 oral histories in the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane University mention influential musicians at Economy Hall, among them Lorenzo Tio, Kid Ory, and Louis Armstrong.

The longevity of the Economie from 1836 to the early 1950s and the permanent location of its hall from 1857 to 1964 speak to its influence. Thousands of people walked through the doors of Economy Hall for every type of social function. The Economie offered the use of its hall to charitable organizations for free and to others for a fee. Meetings of a German workers cooperative, the Société de Cigarers, the Société des Vétérans de 1814–15, Société des Jeunes Amis (young friends), and the seances of the Cercle Harmonique all took place in Economy Hall. The Orleans Athletic Club under the leadership of Walter Cohen rented the hall for Mardi Gras and Saint Joseph night dances during the early twentieth century. Economy Hall saw conventions for laundry workers in 1835, morticians in 1838, and a rally for the Scottsboro boys in 1934.

Over more than a century of its existence, the Economie counted among its members some of Louisiana’s most celebrated Black Americans, including Medard Nelson, Nelson Fouche, Henry Louis Rey, Octave Rey, Arthur Bedou, and Walter L. Cohen. The society touched every part of New Orleans and many places in the world.