Location Is Everything

The upcoming relocation and restoration of the Pacale–Roque House in Natchitoches will reshape the riverfront of Louisiana’s oldest city

Published: November 29, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Tipton Associates

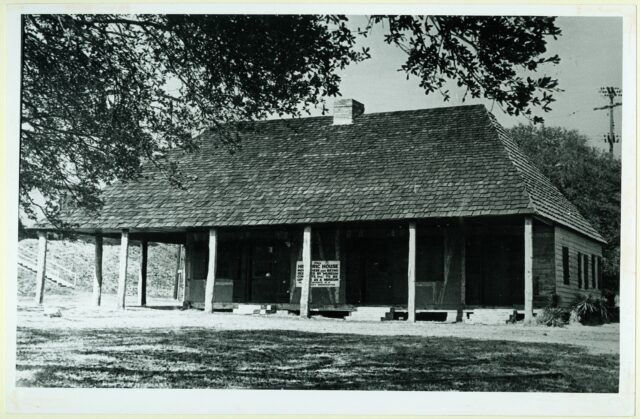

View along the main façade of the Pacale-Roque House, looking west to Cane River Lake.

“We’re gonna pick it up and move it about thirty feet one way and fifty feet the other way,” said George Gaharan, president of Natchitoches-based DSW Construction. Bryon Hume, a partner at architecture firm Tipton Associates, agreed with Gaharan’s assessment. “It’s really simple. We pick the thing up, we rotate it, and we push it back away from the water,” Hume said.

Spoiler alert: It’s not that simple. “The thing,” in this case, is the incredibly fragile, 220-year-old French colonial cottage known as the Pacale–Roque House—perhaps the only structure of its kind in the United States. The Pacale–Roque House is a rare surviving example of the poteaux-en-terre (or posts-in-ground) style of construction found in the earliest American settlements, including Jamestown. The frame of the three-room house is constructed of hand-hewn cypress beams, upright and angular posts connected to a sill that lifts the structure off of the ground, allowing rainwater to run underneath. The house’s walls are made of bousillage, a form of insulation that usually consists of clay mixed with a vegetal binder like Spanish moss. In the case of the Pacale–Roque House, the binder used to strengthen the bousillage is of an unusual type—tufts of horse hair emerge here and there from crumbling patches of the adobe-like material. The house’s unsealed walls allow visitors to inspect the bousillage and even see chip-marks left by axes during construction hundreds of years ago. These imperfections are Hume’s favorite elements of the home.

“We’re looking at a building that has pretty much nonexistent foundations,” Hume said. “The walls are coming apart. The flood of 2016 damaged this property, and its full potential hasn’t been seen since. We have the privilege of helping bring a piece of Louisiana’s history back to life, and that makes for very interesting and worthwhile work.”

As he spoke, Hume gestured toward Front Street, where a few tenacious tourists braved the sweltering heat of a mid-July afternoon. Prior to the catastrophic flooding of Cane River in 2016, visitors to downtown Natchitoches could step inside the Pacale–Roque House during special events and educational programs. Damages sustained during the flood resulted in the house being fenced off and essentially inaccessible. Moving it to higher ground, Hume said, will make the house less vulnerable to floodwaters and secure its future. In addition to relocating the existing house, Hume and his team will build a second structure adjacent to the Pacale–Roque House that will serve as a support building, providing space for storage, event staging, and more. The project also includes a large landscaping and site improvement package. All of this work is on track to be completed in March 2023. “This project has been three years in the making, and we’re finally reaching the point where all of that effort is coming to fruition,” Hume said.

The majestic tree, which has been appraised by the city and valued at a half-million dollars, is located so near the house that its boughs rest on the oversized, cypress-shingled rooftop.

The Pacale–Roque House is important not only because of its age and its architectural significance, but also because of the identity of the man who built it. The house was built by Yves Pacale, a formerly enslaved Black man who’d been permitted by his enslaver, Marie Leclaire Derbanne, to earn extra money working as a carpenter in the Cane River community of Isle Brevelle. In 1801, at age 53, Pacale purchased his freedom for two hundred dollars. He also purchased three, and later freed two, enslaved individuals who may have been his own family members, as well as ninety-one acres of farmland and the raw materials needed to build his home. The house was completed in 1803. It changed hands in 1818, eventually becoming the property of its final resident, Madame Aubin Roque. Roque’s surname has been associated with the cottage ever since, with most Natchitoches locals simply calling it “the Roque House.” A civic organization called Museum Contents, Inc., purchased the cottage in 1967, at which time it was reportedly being used for hay storage, and relocated it twenty-two miles upriver to the bucolic patch of Natchitoches riverfront where it sits today.

The question of why the house was ever placed in its current orientation, essentially bisecting a lovely riverfront park, is one that no one working on the upcoming relocation seems too eager to answer. The August 31, 1967, edition of the Alexandria Town Talk reported that the Pacale–Roque House’s current placement, facing southward between Cane River Lake and Front Street, was selected “to give motorists crossing the downtown bridge a frontal view.” That decision resulted in the house being positioned with its side to the river, an unnatural-feeling orientation that blocks pedestrian flow between the north and south ends of the riverfront.

The house shortly after being moved to downtown Natchitoches. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

“Traditionally, you’d never position a residence with its side or its back to its prominent view,” Hume said. “When we leave this project, the entire riverfront will be much more accessible and pedestrian-friendly. It’ll be much easier for people to move back and forth between the north and south ends of the park.”

Jim Rhodes is chairman of the Cane River Waterway Commission, the governmental entity that has partnered with Natchitoches Historic Foundation on the project and pledged two million dollars toward its completion. Rhodes said that relocating and reopening the Pacale–Roque House will not only alter the appearance, accessibility, and functionality of the Natchitoches riverfront, but will also recast the historical narrative of Louisiana’s oldest city. “This is a working man’s house,” Rhodes said. “This is not something that a plantation owner built for someone to live in, this is something that a free man of color built for himself after purchasing his own freedom. The building is significant, but the really important part is the story. It’s the story that gets lost.”

Architect Bryon Hume inspects the house before renovations. Tipton Associates.

Rhodes sees Pacale as an unsung hero whose life could inspire future generations. “My whole thing is, the story’s not known,” Rhodes said. “Can you imagine when the Oprah Winfreys of the world—these people of magnitude who are trying to help young, Black people understand their history—can you imagine what’ll happen when they get wind of this? This is a story that needs to get out, and once it gets out, you’re gonna have people coming from all over.”

There’s still a lot of work to be done before the Pacale–Roque House can resume welcoming visitors. As with any construction project involving a historic building, the relocation and restoration of the Pacale–Roque House presents unique challenges. “The vintage quality of the building is our biggest challenge,” Hume said. “We can’t historically restore it because there’s almost no documentation of its original configuration. So what we’re doing is a creative rejuvenation of the space, trying to keep its initial heritage intact while recognizing that it provides a service to its community.”

Gaharan added that the project’s many stakeholders—ranging from the Natchitoches Historic Foundation, which owns the Pacale–Roque House, to city government, locals with family ties to the house, event organizers, and tourism promoters—are all keeping a close eye on the project. He understands their passionate interest in the future of the house and appreciates his current role as a steward. “We don’t look at the historic nature of the building as being any sort of obstacle or impediment,” Gaharan said. “We use the historic preservation groups as resources; there are ways that they can help us make this project turn out the way that everyone involved wants to see it turn out.”

“This is a working man’s house…. This is not something that a plantation owner built for someone to live in, this is something that a free man of color built for himself after purchasing his own freedom.”

Another interesting complication presented by the Pacale–Roque House’s current location is the presence—just a few steps outside of the back door—of a towering, 250-year-old live oak. The majestic tree, which has been appraised by the city and valued at a half-million dollars, is located so near the house that its boughs rest on the oversized, cypress-shingled rooftop. The tree’s proximity to the house makes it impossible to perform soil-grading work that would be required to raise the house where it currently sits; any such work would place potentially fatal stress on the tree’s root system. Resituating the house further from Cane River Lake and turning it ninety degrees will not only save the house, but it will also likely lengthen the lifespan and improve the health of the sprawling live oak.

When the restoration and relocation of the Pacale–Roque House is complete, the building will once again host public events and educational programs. Rhodes imagines the house decorated with historically accurate furnishings from a working man’s home, and school buses filled with children visiting the site to learn the inspiring story of Yves Pacale. There is, however, one last challenge standing in the way of that plan: Pacale himself remains mostly a mystery. As Rhodes laid out the knowns and unknowns of Pacale’s life, frustration crept into his voice.

The Pacale-Roque House. Photo by Lane Luckie, Tipton Associates.

“We know where he came from, we know what plantation he worked on, but we don’t know what happened to him,” Rhodes said. “All of a sudden, he simply falls off of the face of the Earth. Anytime I go out in Natchitoches, I could be speaking to his direct descendants and not even know it. Natchitoches is like that. It’s filled with so much history that no one knows.”

Looking back on contemporary media coverage of the house’s 1967 relocation from its original setting in Isle Brevelle to the heart of downtown Natchitoches, one could conclude that the move may have been prompted out of an interest in bolstering tourism rather than an interest in preserving or restoring a fascinating chapter of Louisiana history. This time around—though the house may only be moved “thirty feet one way and fifty feet the other way”—a much greater distance is being covered in terms of the story of Natchitoches. In the Pacale–Roque House, Natchitoches has an opportunity to tell a different kind of story, one that celebrates the agency and self-determination of a Black man who was able to purchase his own freedom and, possibly, the freedom of his family.

Back on the riverfront on that sweltering July day, Hume summed it up. “The story of this house, compared to the story of a plantation, is entirely different,” he said. “Our goal here is that, no matter what your background is, here’s something that we can all celebrate together.”

Chris Jay is a native of Sarepta who is currently pursuing his master’s degree in Louisiana folklife and southern culture at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches. He blogs about southern food at stuffedandbusted.com.