Coartación

Coartación was a legal framework during Spanish colonial rule in Louisiana that allowed enslaved people to purchase their freedom.

Louisiana State Museum Historical Center

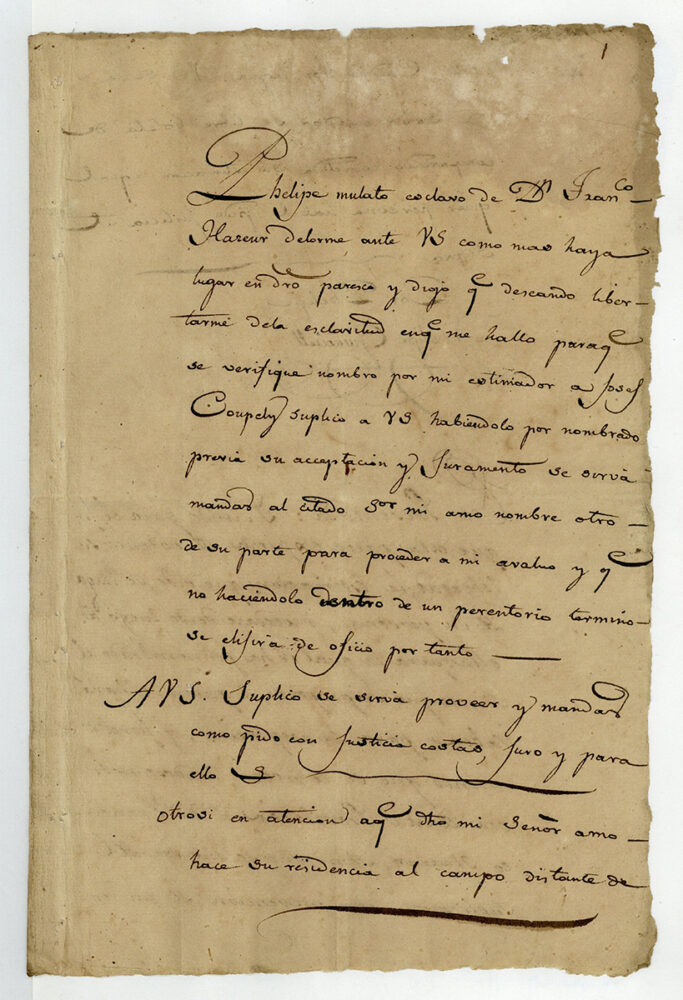

Petition of Felipe, an enslaved mulatto man, to obtain freedom, 1793. “Spanish Judicial Records,” Doc. # 1793-08-06-01.

Coartación was a pathway to freedom in the Spanish empire in which enslaved people could self-purchase their freedom at a fixed price. The horrors of slavery in the Atlantic world included two legal conditions: permanence and inheritability. When enslavers purchased enslaved people, they believed themselves to be buying a lifetime of servitude and obedience, as well as the potential children of that enslaved person. Although some enslaved people found freedom by running away and others were very rarely set free in the wills of owners who died, there were few avenues to freedom for enslaved people. However, a legally protected pathway to manumission called coartación, or self-purchase, developed in Cuba and spread to Spanish colonial Louisiana.

The word coartación comes from the Spanish verb coartar, which means to limit or restrict. In this sense, it referred to the limits on the ownership of the enslaved person granted by the process. In coartación an enslaved person and their owner agreed on a price to be paid for manumission and signed a contract. Typically, once that agreed-upon price had been paid, the enslaved person was granted their freedom. The process of saving up money was difficult and often took years or decades, as enslaved people could only make money through the informal economy, selling products or labor produced outside of the scope of their enslavement.

Despite its limitations, the practice of coartación was often upheld and enforced by local judges, who could compel obedience to coartación contracts. For example, if an owner and an enslaved person could not agree on a price for coartación, a judge would employ appraisers to set a value that was binding on both parties. Each party was appointed their own appraiser, and if their valuations disagreed, a third one would be brought in to make a final decision. Likewise, if an owner refused to free an enslaved person after they had paid the price, enslaved people were able to use the court system to force owners to meet the terms of the contract.

Once an agreement had been reached and the enslaved person had begun making payments, they attained the status of a coartado or coartada until they reached the point at which they were set free. This status was a legal grey area, as some locations allowed coartados more rights than a typical enslaved person but fewer rights than someone who was free.

Coartación was built on the Spanish legal code that had traditionally defined slavery and freedom in the Iberian Peninsula but was not a universally accepted practice in all areas of the Spanish Empire. When the Spanish government gained control of Louisiana, plantation owners who were used to France’s stricter restrictions on manumission were unable to avoid or overrule the practice of coartación. Scholars have tied the legally guaranteed ability to purchase one’s own freedom to significant growth in the number of free people of color in Louisiana during the Spanish period. While there were many success stories, the process was never easy. Coartación frequently involved difficulties and legal battles for those who pursued it as a means of attaining freedom.