Juan San Maló

Juan San Maló (Jean St. Malo) was the leader of a group of self-liberated formerly enslaved people who founded their own maroon resistance community in the bayous and wetlands southeast of New Orleans, in present-day St. Bernard Parish.

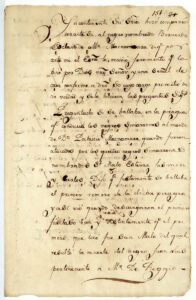

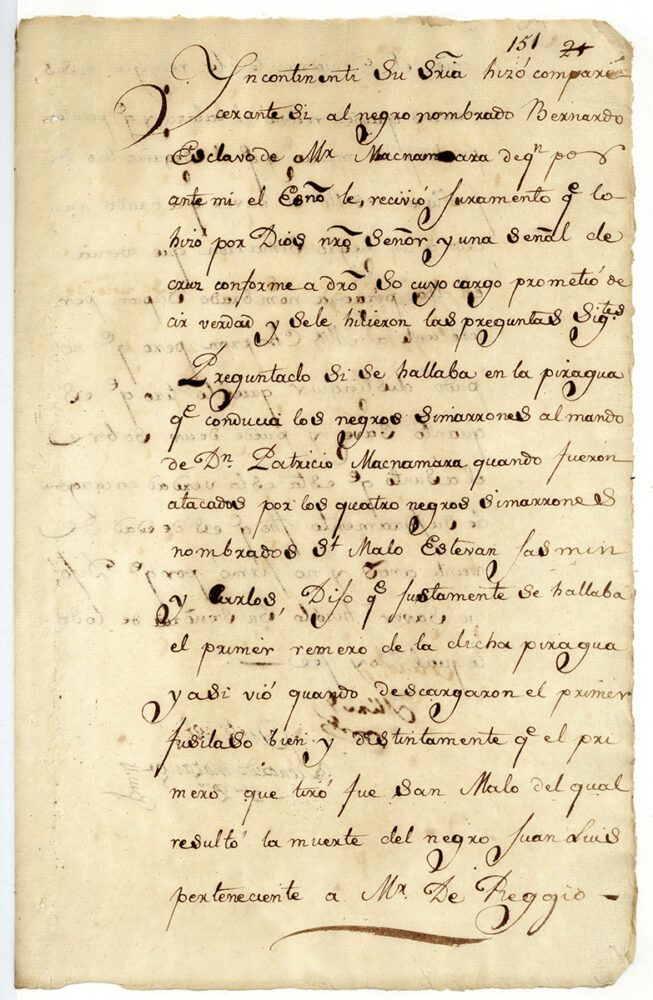

1783-03-01-02, Spanish Judicial Records, Louisiana Historical Center

Spanish judicial records involving Juan San Malo, 1783.

Juan San Maló, also known as St. Maló and Jean Saint Malo, was the leader of a group of maroons who established their own settlements in the bayous and wetlands southeast of New Orleans in the 1780s. Maroons, according to scholar Sylviane Diouf, were groups of formerly enslaved people who had “settled in the wilderness, lived there in secret, and were not under any form of direct control by outsiders.” St. Maló’s community fits this definition perfectly as they settled in the bayous and wetlands that were difficult for the Spanish colonial officials to navigate, attempted to keep their whereabouts unknown, and were engaged in long-running disputes with both local planters and colonial authorities.

Pierre d’Arensbourg, a French-speaking enslaver from the German Coast area north of New Orleans, enslaved St. Maló at one time. Beyond this, almost nothing is documented about St. Maló’s life prior to his leadership of the maroon community. Information about him exists mainly because of the extensive documentation of his trial and subsequent execution after a series of violent confrontations with Spanish authorities.

St. Maló’s maroons lived in multiple settlements across an area downriver from New Orleans known as “Bas du Fleuve,” where they cultivated food, hunted, and fished to sustain themselves. However, they were not fully self-sufficient and maintained complex trade and barter relationships with Indigenous people and enslaved people living on nearby plantations. St. Maló’s band also raided plantations to procure supplies, food, and weapons needed for their survival.

In 1782 the Spanish government began attacking maroon communities as they sought to exert greater control over the borderlands of the colony. In 1783, St. Maló freed a group of maroons who had been taken prisoner by American travelers. In the ensuing violence, one of the Americans was killed. Ultimately, St. Maló’s enduring resistance to Spanish authority resulted in Spanish Governor Esteban Miró sending multiple large raids against the maroon communities in search of St. Maló and his accomplices.

In 1784, one of Maló’s main settlements, Terre Gaillarde, was attacked again by the Spanish. The Spaniards captured St. Maló and most of the residents and brought them to New Orleans for trial. The trial lasted six days, and St. Maló and four other maroons were sentenced to death, while many others received severe punishments. Spanish authorities executed St. Maló on June 19, 1784.

St. Maló’s legacy has been long-lasting. In his time, he served as a symbol of hope and resourcefulness for enslaved and formerly enslaved people and a notorious symbol of the threat posed by permanent maroon communities to Spanish authorities and enslavers. He was memorialized in a Creole folk song that was passed down for generations after his death and in a small fishing town in the area he lived that bore his name.