Belle Isle Salt Mine Collapse

Once one of the most productive salt mines in the country, the Belle Isle Salt Mine was the site of numerous deadly accidents.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

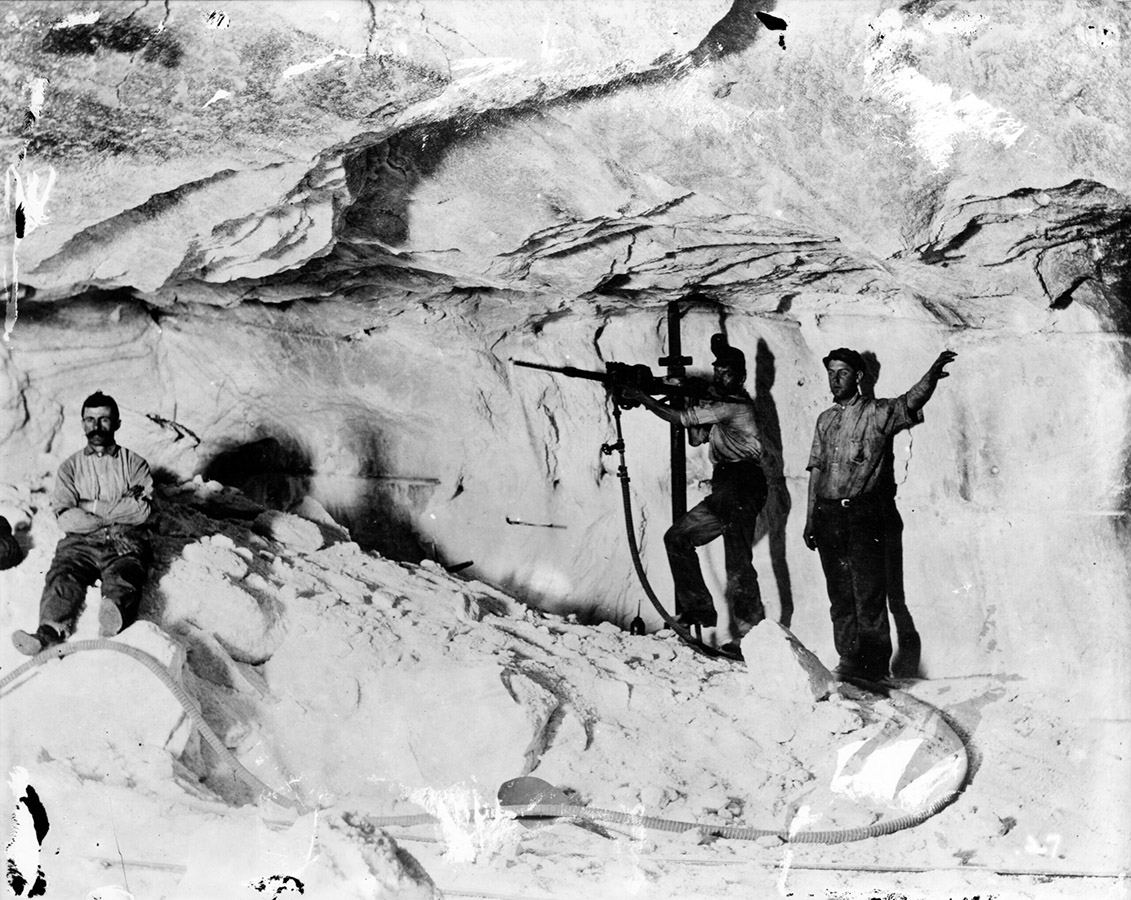

Salt Mine Interior, ca. 1930s.

Joseph Olivier, a former salt miner and mine safety inspector for the Mine Health and Safety Administration, recounted the 1968 Belle Isle Salt Mine disaster that claimed the life of twenty-one miners, including his brother Arthur Olivier and cousins, in a 2008 article for the Advocate in Baton Rouge. Olivier wrote, “I like to think my brother watched his cousins go to sleep. That gives me a little peace of mind.” In 1967, six months prior, federal inspectors suggested that the mine owner, Cargill Incorporated, install a second working mineshaft for safety. Only after the accident did the owners begrudgingly follow this advice. This tragedy was just the first of numerous accidents that ultimately led to the closure and intentional flooding of Belle Isle Salt Mine in 1985.

Belle Isle salt dome, in St. Mary Parish, is the southernmost of Louisiana’s five visible coastal salt domes also known as the “five islands.” The state has 128 identified salt domes, but the five along the coast are the most well-known. These domes were created by massive salt deposits left over one hundred million years ago during the Jurassic period, when a shallow sea that stretched over much of present-day coastal Louisiana evaporated. After millions of years of sediment buildup on top of the salt and geologic pressure, the salt became buoyant and bubbled to the surface, creating the salt dome structures. Other resources such as sulfur and oil intertwined with the salt. The domed landscapes played an important role in the agricultural and industrial development of Louisiana.

Indigenous and colonial people used the raised mounds as landmarks to guide their way through the otherwise flat coastal marshes and prairies. The islands teemed with wildlife, and the fertile soil that surrounded them supported the growth of plantation agriculture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Even with the development of extractive salt and oil industries in the second half of the 1800s, Belle Isle remained a remote outpost of coastal Louisiana. Still, interested parties attempted to access the valuable resources underneath the salt dome.

In the late nineteenth century attempts to extract these resources on Belle Isle proved difficult. Test wells produced little salt and, according to lore, collapsing mountains of salt supposedly buried workers. Another attempt to create a working mine failed in 1898. By the turn of the 1900s additional efforts to set up a salt evaporation plant foundered because an oil film marred the final product. Over the next three decades, repeated attempts to access resources such as sulfur and oil finally produced results in the 1930s when Sun Oil Company sank the first successful oil well on the isle. Over time, Belle Isle developed into one of the top-producing oil fields in Louisiana. However, salt production remained minimal for the next three decades until technological advances allowed the sinking of a mine shaft in unstable ground.

In the early 1960s, Cargill Incorporated, a Minnesota-based food company, reinitiated the attempts at salt mining on the isle and successfully opened a mine shaft in 1962, extracting salt at 1,200 feet and eventually 1,400 and 1,600 feet below the surface. The mine quickly became a top producer nationally, making 400,000 tons of salt in its first year and an average of 1.6 million tons per year by 1968.

In 1968 salt mines were generally considered safer than coal mines. However, safety was never a primary concern at the Belle Isle salt mine, and accidents plagued the operation. Over-pressurized flammable gases such as methane sat within the folds of the salt structure. Mine shaft structures were built of wood, which is resistant to corrosion by salt but also flammable. Underground mine-shaft fires were a constant threat as the shaft represented the only escape route and source of fresh oxygen. Sometime around midnight on Tuesday, March 5, 1968, a fire broke out in the sole mine shaft, most likely caused by an electrical short in the presence of flammable gas. Attempts to quelch the fire took hours and required firefighters to use equipment from nearby oil fields to pump water down the shaft. Although the rescue effort continued into the weekend, all twenty-one miners trapped underground, including Olivier’s brother and cousins, perished. Twenty miners died due to carbon monoxide poisoning, a side effect of fire combustion, and one due to blunt head force trauma, most likely from falling salt.

The tragedy occurred despite the fact that six months earlier federal mine inspectors had suggested the company install a second emergency shaft. After an investigation determined that should a second shaft have existed, essentially all the trapped miners could have escaped, Cargill established a second shaft to the southeast, which opened in early 1972. However, in March 1973 workers reported a leak at the mine level and caverns were evacuated. Surface level workers heard strange noises coming from the shaft a few days later and within hours a sinkhole opened. The sinkhole became 150-feet wide by 50-feet deep and swallowed nearby buildings. Cargill initiated a lawsuit against the cementation company hired to sink the second emergency shaft. The litigation was settled in 1983 with the cementation company found at fault and required to pay Cargill’s damages.

The shaft fire and subsequent sinkhole were not the end of tragedy at the trouble-plagued mine. In 1979 a gas explosion killed five miners, including two more cousins of Joseph Olivier. An investigation into the disaster termed Cargill’s approach to safety as “cavalier” and chastised the supposed attempts at safety regulations as ineffective. In early 1984 the mine was evacuated and permanently abandoned as the structure of the salt dome was in danger of collapse. A leak developed in 1985 and by the end of the year the company purposefully flooded the mine to preserve surface stability.

Now Belle Isle serves once again as a remote marshy outpost and nature preserve reminiscent of the state moniker of the “sportsman’s paradise.”