Code Noir

The Code Noir provided rules for how colonists treated enslaved people as well as how people of European and African ancestry interacted in French colonial Louisiana.

This entry is 6th Grade level View Full Entry

The Historic New Orleans Collection

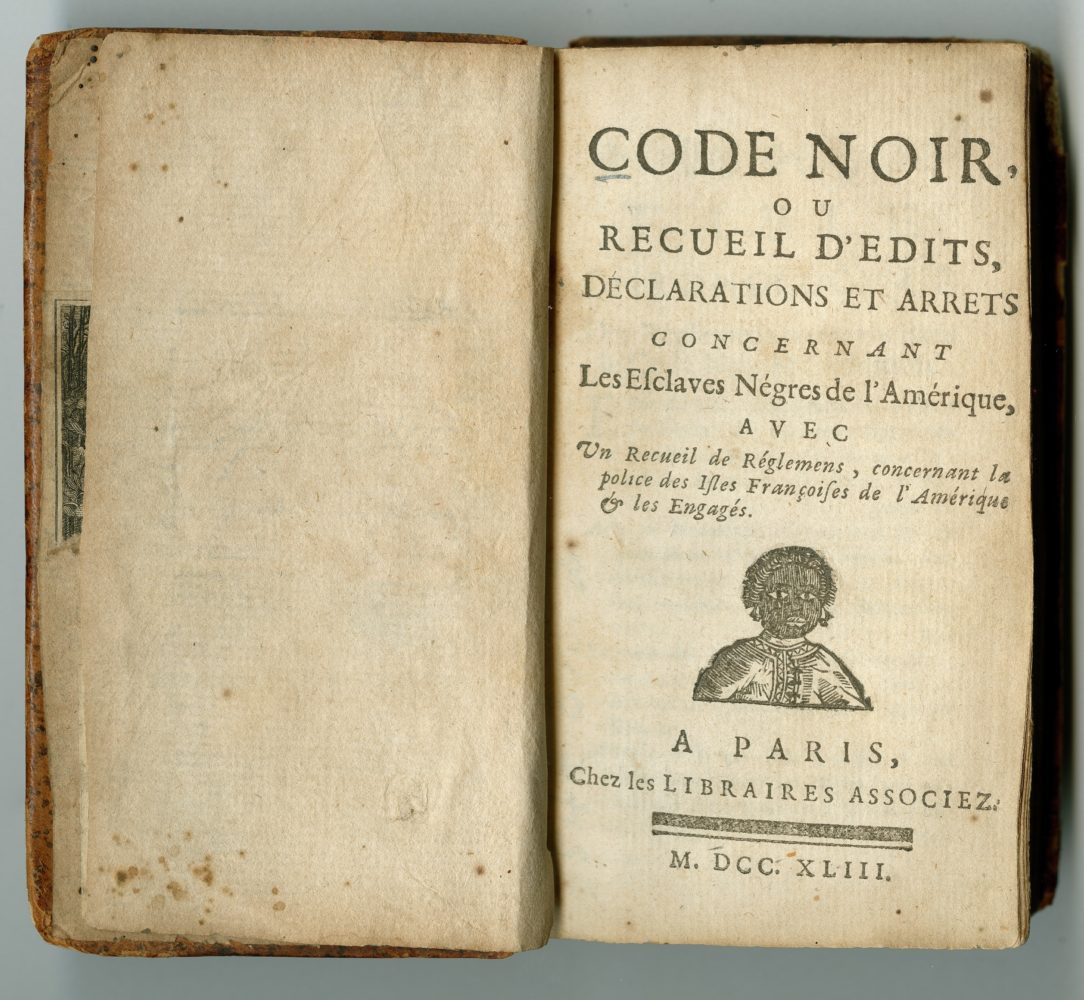

Code Noir of 1724 as printed by les Librairies Associez of Paris, 1743.

What was the Code Noir?

The French government issued the fifty-five articles of the 1724 Code Noir specifically for the Louisiana colony, replacing an earlier code from 1685. This new Code Noir was an attempt by the French government to control the lives of people in French colonial Louisiana, particularly men, women, and children of African descent. The first eleven articles created rules for religion in the colony, including the expulsion of Jewish people, the recognition of Roman Catholicism as the only legitimate religion, and the requirement that all slave owners baptize enslaved people, including newly arrived Africans, in the Roman Catholic Church.

As a legal document the Code Noir provided rules for how colonists treated enslaved people as well as how people of European and African ancestry, including free people of color, interacted in Louisiana. The 1724 code didn’t explicitly address or regulate the practice of enslaving Native Americans in Louisiana. These rules stated that enslaved people were considered property and could be passed from generation to generation or sold for their owners’ profit. The rules also made clear that the children of an enslaved women were the property of her owner regardless of whether the father was free or enslaved. One of the articles prohibits enslaved people from owning anything—no matter how small or of how little of value. Another article forbade marriage between Black and white people—even when both were free. Slave owners were supposed to make sure that enslaved people were, when given permission by their owners, married in the Roman Catholic faith. Owners could free enslaved people, but only with the permission of the colony’s government, the Superior Council.

The Code Noir placed some restrictions on slave owners and set minimum standards for the care and treatment of enslaved men, women, and children. For example, the code established Sundays as a day off for enslaved people and required owners to care for sick and elderly enslaved people. The historical record is clear, however, that enslaved people weren’t treated better in French Louisiana than elsewhere in North America.

The Code Noir limited how slave owners could punish enslaved people themselves, stating instead that the French colonial government would carry out punishments. For example, when the government found enslaved people guilty of illegally gathering in crowds, they could whip them for the first offense and then brand them with the mark of a fleur-de-lis after multiple offenses. In addition to lashes and branding, when enslaved people ran away repeatedly, the government could cut off their ears and cut their hamstrings. The government even put some of these enslaved people to death. Less severe penalties, usually fines, awaited white people who attempted to marry Black people, as well as the priests who conducted such marriage ceremonies. Enslaved people weren’t allowed to carry weapons, own property, marry white people, or gather with enslaved people belonging to other owners. And free Black people faced fines and could even be re-enslaved as punishment for helping enslaved people flee from slavery.

French officials wanted the Code Noir to create a clear social structure that ensured white colonists controlled the social, legal, and economic hierarchy. However, the laws didn’t completely stop illegal interactions between white and free and enslaved Black people or between Native Americas and enslaved people who ran away. Just as people in the present day don’t always follow the law, people in colonial Louisiana didn’t always follow the Code Noir. They found ways to subvert and resist despite the harsh penalties they faced if caught.