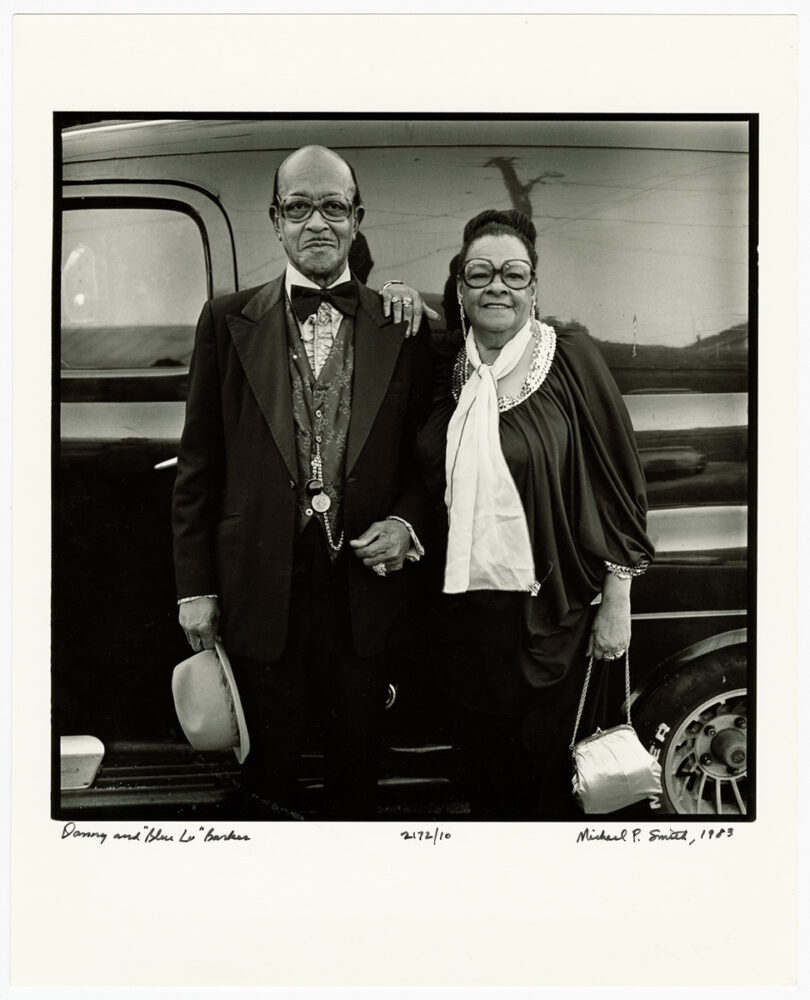

Danny and Blue Lu Barker

New Orleans’s first couple of jazz.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Danny and “Blue Lu” Barker. Photo by Michael P. Smith

After thirty-five years of pursuing their music careers in New York City, Danny and Louise “Blue Lu” Barker returned to their native New Orleans in 1965. Becoming beloved role models for generations of jazz musicians, the Barkers and their musical and educational influence continued decades after the couple’s deaths.

During his years away from New Orleans, Danny Barker, a guitarist, banjo player, singer, and songwriter, performed with fellow New Orleanian Jelly Roll Morton, Lucky Millinder, Benny Carter, and Cab Calloway. A prolific session musician, Barker and his powerful rhythm guitar contributed to recordings by Lena Horne, Ethel Waters, Billie Holiday, James P. Johnson, Lionel Hampton, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, and many more. From 1965 through the early 1990s, Barker’s multiple roles in New Orleans—historian, music journalist, educator, gigging musician, and raconteur—inspired a second era for the traditional New Orleans jazz revival that began in the 1940s. For a new generation of musicians and jazz fans in New Orleans during the 1970s and 1980s, Danny and Blue Lu Barker personified the city’s jazz history. Danny Barker also mentored dozens of aspiring jazz artists, including Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Herlin Riley, Leroy Jones, Shannon Powell, Dr. Michael White, Gregory Davis, James Andrews, and Gregg Stafford.

From New Orleans to New York: Swing Bands, Beboppers, and Traditional Jazz

Daniel Moses Barker was born on January 13, 1909; Louise Dupont (she later took the stage name Blue Lu), on November 13, 1913. Danny and Blue Lu came of age in the 1920s, after a first wave of pioneering New Orleans jazz musicians began migrating from the Deep South. Danny Barker’s uncle and drum instructor, Paul Barbarin, was a prominent musician, one member of a family of nearly forty professional musicians dating to the nineteenth century. Danny Barker moved from ukulele to banjo and guitar and began playing professionally, first with a street band, the Boozan Kings, and later with the touring bluesman, Little Brother Montgomery.

Blue Lu Dupont’s family ran a grocery store and pool hall that prospered selling bootleg liquor during Prohibition. In 1930, at sixteen years old, Blue Lu married Danny Barker and, a few months later, moved to New York City with him. When Danny Barker wasn’t working in a band, he freelanced and promoted his wife’s singing. The pair recorded for Decca in the late 1930s and later for the Apollo and Capitol labels. In 1938 Blue Lu Barker’s recording of a risqué song she’d co-written with her husband, “Don’t You Make Me High,” became a hit. The song would later be known as “Don’t You Feel My Leg.” In 1945 Danny Barker recorded with future beboppers Dexter Gordon and Charlie Parker. However, mid-twentieth-century modern jazz wasn’t for him and, by the early 1960s, he was leading a band at Jimmy Ryan’s, a traditional jazz club on New York City’s 52nd Street.

Return to New Orleans

Following the couple’s return to New Orleans in 1965, Danny Barker worked as assistant to the curator at the recently opened New Orleans Jazz Museum. The position gave him a reliable income while he pursued his interest in jazz history, especially jazz in New Orleans. Barker helped others with their research while he wrote his autobiography. In 1969 he was among the leaders of an effort to commission the statue of New Orleans’s most famous jazz musician, Louis Armstrong, that now stands in Louis Armstrong Park. In 1970 Barker founded the Fairview Baptist Church Brass Band, naming twelve-year-old trumpeter Leroy Jones as its first leader. Dozens of locally and nationally important musicians passed through the band, and Barker is credited for reviving the New Orleans brass band tradition.

Blue Lu Barker’s legacy received attention in 1973 when roots-music chanteuse Maria Muldaur recorded “Don’t You Make Me High” for her solo album debut. After the album’s surprise commercial success, Muldaur sent a gold record award to the Barkers and, with the help of Mac Rebennack, aka Dr. John, arranged for the couple to receive songwriter royalties for “Don’t You Make Me High.” In 2018 Muldaur released the Blue Lu Barker tribute album Don’t You Feel My Leg. As the 1980s approached, Danny Barker, with the assistance of British editor Alyn Shipton, concentrated on the notes and fragmentary memoirs he had been collecting for decades. He subsequently published two books, A Life in Jazz (1986) and Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville (1998). Although Danny Barker appeared on as many as 1,000 recordings as an accompanist, his 1988 album, Save the Bones, recorded when he was seventy-nine years old and released by the local Orleans Records, best showcases his performance strengths: faultless timing, masterful storytelling, and droll humor. In 2022 Tipitina’s Record Club reissued Save the Bones in a premium vinyl edition.

In 1991 the National Endowment for the Arts named Danny Barker one of its jazz masters, the highest honor the United States bestows on jazz artists. In his later years, he performed for private events and appeared weekly at the Palm Court Jazz Café in the French Quarter. He performed for the final time on New Year’s Eve at Preservation Hall in 1993 and died on March 13, 1994. The Black Men of Labor, a benevolent society dedicated to honoring African American men in the work place and preserving traditional jazz music, paid tribute to Danny Barker with its first jazz funeral parade.

Blue Lu Barker retired from performing after her 1989 appearance at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. She died on May 7, 1998. But the Barkers were not forgotten, especially in New Orleans. In 2015 guitarist and banjo player Detroit Brooks founded the Danny Barker Banjo and Guitar Festival. In 2016 the Historic New Orleans Collection published a new edition of Barker’s autobiography, A Life in Jazz. In 2018 Muldaur paid tribute to Blue Lu Barker with the album Don’t You Feel My Leg—The Naughty Bawdy Blues of Blue Lu Barker. Muldaur met the Barkers in 1974, after they accepted her invitation to attend her show in New Orleans. “We were great friends from that point forward,” Muldaur said in 2019. “It was an honor to know them. They were both so charming and cool, and such unique, soulful people.”