Filipinos

Louisiana is home to the earliest Filipino American community in the United States.

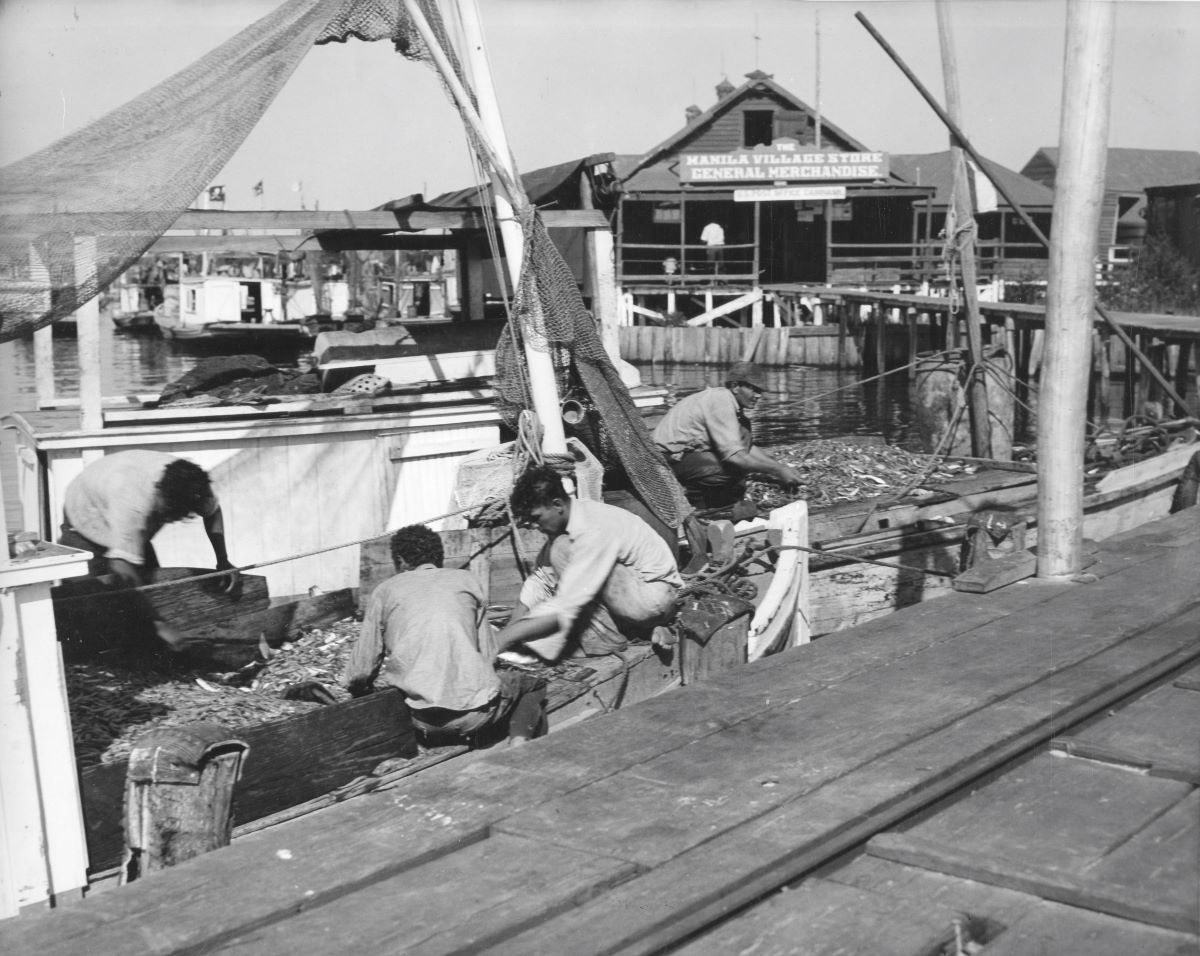

State Library of Louisiana

Unloading the Day’s Shrimp Catch in Manila Village, Louisiana.

Louisiana was home to one of the earliest Asian American communities in the United States. Filipinos first arrived in Spanish colonial Louisiana as sailors on Spanish vessels in the eighteenth century. They settled in the marshes of St. Bernard and Jefferson Parishes and were pioneers of Louisiana’s commercial seafood industry. These early settlers were the foundation of a Filipino American community fortified through centuries of migration. Now more than sixteen thousand Louisiana households have Filipino ancestry.

Early Settlers

The earliest Filipino settlers were sailors who left their ships in New Orleans and found their way to sparsely populated wetlands on the southern shore of Lake Borgne and barrier islands around Barataria Bay. They established the settlements of St. Malo (circa 1830s) in St. Bernard Parish and Manila Village (circa 1880s) in Jefferson Parish. Filipino seamen who heard of these fishing communities traveled to Louisiana to join these settlements. They found seasonal work as fishermen, trappers, moss collectors, and, after slavery was abolished in 1865, as plantation workers. With no Philippine-born women, male Filipino settlers married across ethnic and racial lines or, when possible, married daughters of earlier Filipino settlers. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Filipino American population of Louisiana was greater than that of all other states combined.

St. Malo

Filipinos living in the marsh on the southern shore of Lake Borgne were instrumental in developing the state’s commercial fishing industry. Filipino fishermen established St. Malo at a site previously settled by Indigenous peoples and later by Maroons (people who escaped slavery) led by Juan San Maló. In the 1860s their proximity to prime fishing grounds positioned Filipino fishermen to meet the increased demand for fresh seafood in New Orleans. When Lafcadio Hearn visited in 1883, St. Malo was the largest fishing village on Lake Borgne, a prosperous community of more than one hundred and fifty Filipinos who lived in large cypress buildings constructed over the wetlands.

These fishermen and their descendants formed the foundation of the Filipino community in Greater New Orleans. In 1870 they established the first Filipino American community organization in the United States, Sociedad de Beneficencia de los Hispanos Filipinos. They used Spanish because the Philippines was still a Spanish colony at the time. Filipinos often associated with other Spanish-speaking communities, like the Isleños. The benevolent society raised money to support the community in difficult times, including burial for members in a society tomb at St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery in the Upper Ninth Ward in New Orleans. The tomb is one of the oldest Asian American tombs in the South.

Manila Village

Filipino fishermen were pioneers in the commercial shrimp industry. They dried shrimp in Louisiana for generations before Chinese merchants commercialized the industry in the 1870s. Shrimp harvesting and processing were coordinated from platform villages. The shrimp drying process included using football-field-sized platforms. To remove the shells from dried shrimp, workers would “dance” on the shrimp, shuffling canvas-covered feet across them until the dried shells turned to powder. Filipino American entrepreneurs established several platform villages, including Manila Village and Clark Cheniere in Barataria Bay. Manila Village was the largest platform village and came to symbolize the Filipino presence in the region. Bernard Docusen worked on his father’s shrimp boat before he became a successful professional boxer. Descendants of Filipino fishermen still reside in the region.

Growing Community

US immigration policy determined Filipino migration to Louisiana. The community grew during the Philippines’ US colonial period (1899–1946), suffered when US policy set restrictive quotas on Filipino immigration, and surged when the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished quotas. During the colonial period Filipinos were non-citizen US nationals free to settle in the United States without restriction. The designation increased migration to Louisiana, particularly among seamen. Descendants of early settlers and recent immigrants, including Filipino veterans who joined the US Navy in the Philippines, contributed to a vibrant Filipino community in New Orleans. Filipino boarding houses, restaurants, and bars around the French Market supported a large contingent of merchant marines working on ships that frequented the bustling port.

Filipino cultural identity remained strong across generations due in part to the practice of Philippine-born men marrying the daughters of earlier Filipino settlers. Community events like dances, Mardi Gras balls, and gatherings at Filipino establishments like the Filipino Colony Bar in New Orleans’s Marigny neighborhood helped maintain community pride. A highlight for the community came in 1935 with participation in the inaugural Elks Krewe of Orleanians parade for Mardi Gras in New Orleans. The community float featured a group of young Filipino Americans in traditional Filipino clothes. The float, which flew both Philippine and American flags as an expression of dual cultural identity, won an award for being the best decorated. In 1948 the Philippine government opened a consulate in the city. Consulate staff and their families helped strengthen ties between the community and the Philippines.

After the 1965 Hart-Cellar Immigration Act removed quotas on the number of Filipinos allowed to immigrate to the United States, Louisiana saw an influx of Filipino professionals and their families. Filipinos migrated across Louisiana to contribute to industries like healthcare, energy production, and education. Recent immigrants took the lead in community organizations as descendants of earlier settlers increasingly identified more with Louisiana and less with the Philippines. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Filipino healthcare workers and educators came to the state to fill a labor shortage. Three hundred and fifty teachers were illegally trafficked to the state in 2007 and 2008 by a Philippine labor agency. They won a class action suit in 2010 to recover some of the tens of thousands of dollars they were each forced to pay to the agency.

Descendants of earlier generations and recent immigrants make up a vibrant Filipino community. Filipino community organizations across the state hold events to celebrate the culture of the Philippines and history of Filipino Louisiana. Each October, during Filipino American History Month, Filipino Americans around the country look to Louisiana as the setting for the first chapter in Filipino American history.