New Orleans Flood of 1849

The flood of 1849 was the worst in New Orleans history until Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

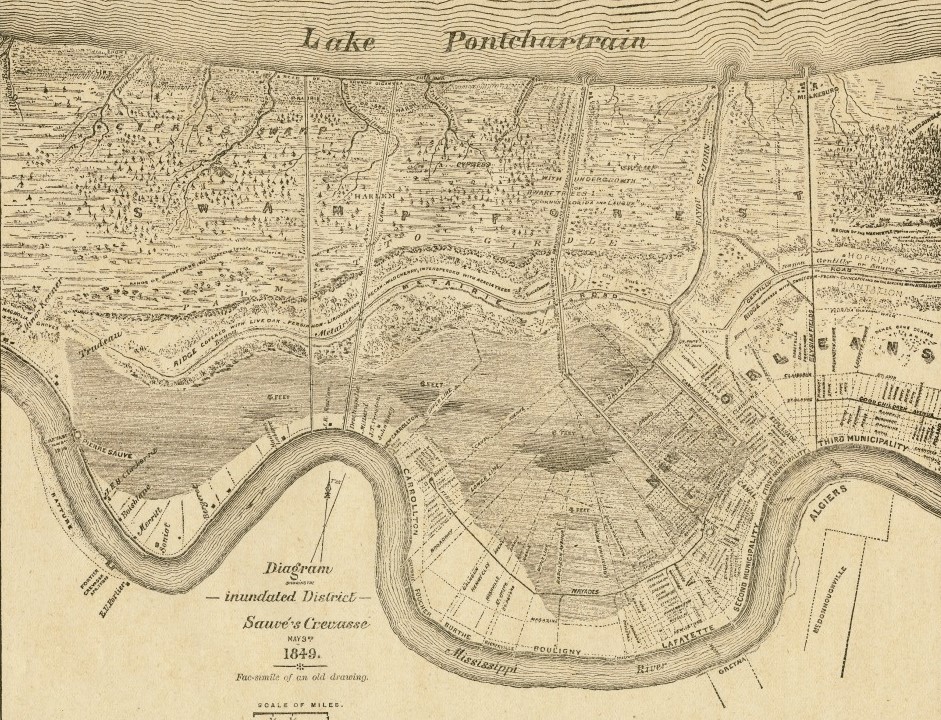

Diagram Showing the Inundated District, Sauvé’s Crevasse.

On May 3, 1849, the Mississippi River broke through the levee at Pierre Sauvé’s Providence Plantation, seventeen miles upriver from the center of New Orleans. By May 8, waters reached the back of the city’s Second Municipality (roughly today’s Central Business District). Within days the river flooded about 220 occupied city blocks, surrounded two thousand homes and apartments with water, forced nearly twelve thousand people to flee, and covered most of the cemeteries with six feet of water. According to historian Harry Kmen, several residents died from drowning, starvation, and even snake bites. In terms of the proportion of the city covered with floodwaters, the 1849 flood was the worst in New Orleans history until Hurricane Katrina in 2005. As the 1849 floodwaters receded, the disaster laid bare the limits of human engineering of the Mississippi River via the levee system, the political and other divisions that plagued the city, and the environmental challenges the city of New Orleans has historically had to confront.

As floodwaters inundated the city, some New Orleanians died in or near their homes, tens of thousands of the city’s poorest residents (around 10 percent of the city’s population) were displaced, and others threatened one another with violence over which parts of the city should be protected and which parts sacrificed. Food shortages and a lack of clean drinking water exacerbated the situation. Floodwaters reached four blocks into the rear of the French Quarter and into what is now the Central Business and Garden Districts. Snakes and alligators were rumored by the city’s newspapers at the time to roam the inundated streets and buildings. Engineers blamed elected officials for refusing to fund necessary protection measures and ignoring sound scientific advice, while politicians blamed engineers and other politicians for the chaotic response.

Divided City

At the time of the flood, New Orleans was organized into three municipalities, each with its own government and budget. The First Municipality comprised the French Quarter, or old city core. The Second Municipality comprised the upriver “American” district above Canal Street, and the Third Municipality comprised the downriver Marigny area below Esplanade Avenue. Upriver from the Second Municipality were the towns of Lafayette and Carrollton (today within New Orleans), with plantations extending beyond the towns upriver for miles. The three municipalities maintained the levees within city limits, but the towns of Lafayette and Carrollton and private landowners shouldered the responsibility to maintain the levees upriver from New Orleans. This unique municipal governing structure, whereby each municipality had its own council of elected aldermen with full budget authority, made coordinating a crisis response difficult. Layered over the three New Orleans municipalities was an elected mayor with limited authority, especially concerning budgetary matters. City engineers, especially Second Municipality surveyor George T. Dunbar, criticized elected officials for doing little to bolster New Orleans’s defenses against a river flood, even as the Mississippi River rose to unprecedented heights in the spring of 1849. Dunbar called for major infrastructure improvements, including constructing a spillway to connect the Mississippi River with Lake Pontchartrain in the event of a high river. This idea was not realized until the Bonnet Carré Spillway opened in 1931. Second Municipality aldermen dismissed Dunbar’s proposal in 1849 for being too costly.

When the engorged Mississippi River broke its banks at Pierre Sauvé’s property around 4 p.m. on May 3, the divided city government scrambled to construct temporary levees along the north side of the French Quarter and in the western wards of the Second Municipality and to repair the breached levee upriver. River water soon filled the back parts of the Second Municipality—the lowest ground farthest from the banks of the Mississippi River. The city’s poorest residents—primarily recent Irish and German immigrants—lived in the rear parts of the city, where housing was cheapest and more vulnerable to flooding. Many Irish and German children remained trapped in their homes, and some of their parents drowned trying to find food.

Political Scandal

The city’s effort to stop the flood quickly became a political scandal. Residents and representatives from towns and communities upriver disagreed with New Orleans officials about how best to handle the situation since the construction of temporary cross levees to prevent floodwaters from flowing into the city could then inundate upriver areas as water continued to flow through the crevasse. Each ward in the Second Municipality responded according to its own perceived best interests. For example, opposing groups of men, armed with spades and shovels, faced off over the construction of a new temporary levee along the New Canal, with one side seeking to build it higher and the other—led by a Second Municipality alderman—seeking to tear it down. City newspapers ran titles such as “Who Is to Blame?” as they sought accountability from city officials.

Aldermen of the Second Municipality Council provided skiffs and other boats to residents in its flooded areas. Editors of the Daily Crescent newspaper thought that “something more should have been given than mere transportation.” The boats were a convenience, but “many poor people, who are driven from their homes by the flood, know not where to go or what to do, when they get to dry land.” When some members of the Second Municipality Council proposed cash payments to the poor to help them acquire basic supplies and housing, others struck down the idea as “charity” and insisted that private sources should pick up the slack. As the flood stretched into weeks, city officials ordered engineers back to Sauvé’s levee with Irish and enslaved laborers who repaired the breach by June 20, resulting in slowly receding waters after that date.

Impacts

The few years following the 1849 flood saw major changes in the organization of New Orleans’s city government. By early June 1849, while the Mississippi River still flowed through the crevasse at Sauvé’s plantation, city newspapers such as the Daily Crescent argued in favor of municipal consolidation. In the mayoral election of 1850, incumbent Mayor A. D. Crossman ran successfully on a platform of revoking the city charter and establishing a unified city government. A vote by New Orleans residents and then state legislative action reorganized New Orleans and neighboring Lafayette into a single municipality in 1852, giving the mayor’s office more authority to handle emergencies. City politicians who opposed the sufficient funding of flood prevention and resisted providing relief to survivors in 1849 faced intense criticism, with some resigning their office or declining to seek reelection. Civil engineers gained new prestige and responsibilities in 1849 and thereafter as the city, state, and national governments sought up-to-date scientific data and plans to prevent a similar catastrophe from happening again. Dozens of engineers flocked to New Orleans and offered a multitude of plans and reports. Lastly, the 1850s brought renewed prosperity to New Orleans. Growth was fueled in part by city reform and engineering projects but also by the boom in cotton prices, staple crop production, and the related expansion of slavery and the slave trade in Louisiana and the lower Mississippi River Valley.