Native Americans in Twentieth-Century Louisiana

Native American communities in Louisiana are culturally diverse with unique histories.

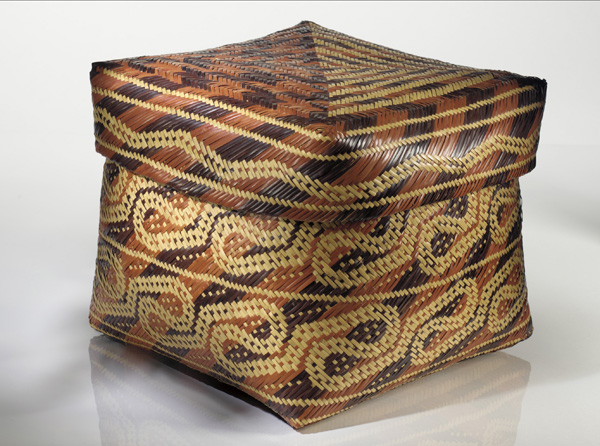

Courtesy of National Museum of the American Indian

Basket with cover. Thomas, Ada (Artist)

The US Census Bureau estimates that more than 32,000 Native Americans lived in Louisiana in 2020. The federal government currently recognizes four Louisiana tribes, the Chitimacha Tribe, Coushatta Tribe, Tunica-Biloxi Tribe, and Jena Band of Choctaw Indians, and the state recognizes eleven additional tribes, the United Houma Nation, Choctaw-Apache Tribe of Ebarb, Clifton Choctaw Tribe, Adai Caddo Indians of Louisiana, Four Winds Cherokee, Louisiana Band of Choctaw, Natchitoches Tribe of Louisiana, Pointe-Au-Chenes Indian Tribe (PACIT), and the Biloxi-Chitimacha Confederation of Muskogees (BCCM) which is comprised of the Bayou Lafourche Band, the Isle de Jean Charles Band (now the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation), and the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band. Louisiana also has four unrecognized tribes, the Talimali Band of Apalache, Atakapa-Ishak Nation, Louisiana Choctaw Turtle Tribe, and Chahta Tribe, as well as three American Indian organizations, the Louisiana Intertribal Council, Louisiana Indian Education Association, and Louisiana Indian Heritage Association.

Culturally diverse with unique histories, American Indian communities in Louisiana have nevertheless experienced similar challenges and opportunities. Although many tribes practiced horticulture for generations, lack of land and capital for equipment prevented Louisiana tribes from establishing extensive farms or ranches in the twentieth century. The Chitimachas controlled only 261.54 acres when the federal government placed the land in trust, and Tunica-Biloxis controlled only 129.5 acres by the early twentieth century. Timber companies bought up much of the land homesteaded by Coushattas in the early twentieth century and purchased mineral rights from those who refused to sell their land, clear-cutting it. The discovery of oil and gas on Houma, PACIT, and BCCM lands in the 1920s led to similar land loss through foreclosure, fraud, and coercion. In addition, the Choctaw-Apaches sold much of their land in the 1970s and were removed to make way for Toledo Bend Reservoir.

Despite these obstacles, Indians in Louisiana did farm. Tunica-Biloxis grew cotton, corn, and vegetables on small plots of land, and many Indians owned cows, horses, pigs, and chickens. Indians took jobs in the timber and oil industries and on farms. They supplemented their incomes by cutting cordwood, picking cotton, harvesting swamp moss, gathering blackberries, hunting, fishing, trapping, shrimping, oystering, and tanning hides. Indian women often cleaned the homes of local white people, took in laundry, and sold handcrafted baskets. Today, Indians in Louisiana run their own businesses and work in all areas of the economy. However, some Indians continue to work in industries that have become traditional like shrimping and oystering, while others still sell traditional crafts, such as baskets.

Louisiana’s American Indian artists, including Chitimachas, Choctaws, Coushattas, and Houmas, have carried their basket-making traditions into the twenty-first century, and museums and collectors recognize these craftspeople for their skill and creativity. In addition to basketry, traditions concerning burial, dance, folklore, food, music, woodworking, and other activities continue in Louisiana’s Indian communities. For example, Houma artists still create elaborate woodwork; the Chitimacha Tribe teaches traditional dances to their community’s children, and the Coushatta Tribe prepares traditional corn soup for community events.

Some of Louisiana’s Indians have also maintained their languages. The Choctaw language survives in the Jena Band, but not among the other Choctaws in Louisiana, and the Koasati language is still used in the Coushatta community. Other American Indian communities have lost their native languages. Some of these communities retain an Indian dialect of French, and others are trying to resurrect their languages using notes and recordings gathered by ethnologists and linguists. The Chitimacha Tribe has worked with Rosetta Stone to develop software to teach their language to tribal members, and members of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation are attempting to reclaim their language using a dictionary created by the Bureau of Ethnology in the 1930s.

Most Indians in Louisiana converted to Christianity in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, and although Indian communities in Louisiana still organize their communities through various kinship systems, churches became central to the social life of many communities. Louisiana’s Indians borrowed cultural elements such as powwows and fry bread from other Indians and made them new traditions in their communities. Today, the Coushatta Tribe, Jena Band of Choctaws, Tunica-Biloxi Tribe, Adai Caddo Tribe, Biloxi-Chitimacha Confederation, Choctaw-Apache Community, Four Winds Tribe, United Houma Nation, Atakapa-Ishak Nation, Chahta Tribe, and Louisiana Indian Heritage Association, all host powwows, and representatives from all communities attend them.

Louisiana’s Native Americans wanted both traditional and western education for their children to maximize their opportunities. For many, educating their children became a central issue. Local school boards often classified Indians as “colored” and barred them from white public schools. Refusing to send their children to segregation-era African American schools, Native parents took legal action, and Native communities pushed for Indian schools. Initially, very few Indian children attended school. In 1913, Houma Henry Billiot tried gain a court order forcing Terrebonne Parish to allow his children to attend school with white children but lost because the court ruled that his children were “colored.” In addition, Jena Choctaw parents refused to send their children to school until the Penick Indian School was opened in 1932. Coushattas were an exception to the usual pattern. They paid local taxes and sent their children to an Indian elementary school run by the parish, and Elton’s public school welcomed Coushatta students who desired schooling beyond the first few grades.

In 1934, after several Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) studies in Louisiana and a shift in Indian policy, the federal government established a school on the Chitimacha reservation. The same year it began funding public education for the Jena Choctaws and did the same for Coushattas the next year. The BIA took over operation of the Coushatta elementary school in 1942. Officials closed Penick Indian School at the beginning of World War II, and after the war, the local school board allowed Jena Choctaw children to attend the white public schools. The BIA relinquished responsibility for Coushatta education in 1953, returning control to state and parish governments. The state opened an elementary school for the Houmas in the 1950s, which operated until a suit filed by Houma Margie Naquin led to desegregation in 1969. Today, the Chitimacha Tribe operates a community school for grades pre-kindergarten through eight, which teaches the students the Chitimacha language as well as the conventional state curriculum, but most American Indian children in Louisiana today attend integrated public and parochial schools.

The US Congress recognized the Chitimachas as an Indian tribe in 1925, and the BIA had extended services to the Coushattas and Jena Choctaws in the 1930s. However, in 1953, the agency discontinued services to both communities and proposed termination legislation for the whole state the next year. Congress never passed the legislation, but neither did the government reinstate services. In the 1970s, several Louisiana communities banded together to form the Louisiana Inter-Tribal Council. During the same period, the Louisiana legislature acknowledged the Choctaw-Apaches, Clifton Choctaws, Coushattas, Houmas, Jena Choctaws, and Tunica-Biloxis and created a state office for Indian affairs. In the 1990s, the state extended recognition to the Adai Caddos and Four Winds Cherokees. The BIA administratively recognized the Coushatta Tribe and reinstated services to them in 1973, and the Branch of Acknowledgement and Recognition, created by the BIA in 1978, recognized the Tunica-Biloxis in 1981 and the Jena Band of Choctaws in 1995. The Houmas filed a petition for federal recognition in 1985 and received negative proposed findings in 1994. The United Houma Nation sent a rebuttal two years later, but in the wake of this initial failure, four communities initially within the United Houma Nation broke away, three formed the Biloxi-Chitimacha Confederation of Muskogees, (BCCM) and all four petitioned for state and federal recognition. The state legislature recognized the Bayou Lafourche, Grand Caillou/Dulac, and Isle de Jean Charles Bands, (BCCM) and the Point-Au-Chien Tribe in 2004. Most of the state-recognized tribes continue to seek federal recognition, and unrecognized tribes petition for the state’s acknowledgement.

Current BIA rules for federal acknowledgement make the process difficult, and Louisiana recently followed suit, giving new claimants an increasingly onerous path to state recognition. Despite these difficulties, communities continue their efforts, in part, because many state and federal programs meant to benefit Indian people require official government acceptance that a community is an Indian tribe. For example, designation as an Indian artist or an Indian student requires state recognition of the individual’s community, and BIA funding requires federal recognition. Additionally, the sovereign status that comes with federal acknowledgment also provides opportunities for economic development, including Indian gaming. In 1980, when the Federal District Court of Florida ruled in Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Butterworth that states could not regulate any legal games of chance on Indian reservations, gaming became a viable option for Louisiana’s federally recognized tribes. The Coushattas authorized a bingo operation in 1984, and the Chitimachas did the same the next year.

After the Supreme Court agreed with the legal thinking of the Florida court, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988. This act regulated Indian gaming and made provisions for negotiations between the state and tribes wanting to open Las Vegas style casinos. In 1992 the Chitimacha, Coushatta, and Tunica-Biloxi tribes, the only federally recognized communities at the time, negotiated compacts with the state and opened casinos over the following three years. The Chitimachas converted their bingo facility by adding slots and table games, but the Tunica-Biloxis and Coushattas, whose bingo operation was short-lived, built new facilities. After gaining federal recognition, the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians made headlines when they negotiated with the governor to build a casino in Vinton, which was nowhere near their home in central Louisiana but strategically located to take advantage of the lucrative business coming from Texas. Opposed by both riverboat casino operators and competing Indian tribes, the federal government refused to approve the compact in 2003, and the Jena Band remains the only federally recognized tribe without a casino in Louisiana.

The Jena Choctaw effort and other potential expansions of gaming in Louisiana and Texas brought difficulties for gaming tribes as their governments hired lobbyists to influence local, state, and national policy. The scandal surrounding Jack Abramoff involved both the Chitimacha Tribe and the Coushatta Tribe who were clients of the lobbyist. In the wake of the Abramoff ordeal, Louisiana’s American Indian communities move forward with efforts to improve their communities. Revenues from gaming have allowed the Chitimachas, Coushattas, and Tunica-Biloxis to improve their standard of living, invest in their culture, and reclaim some of their land. The Chitimacha Tribe has bought back almost 1000 acres of land lost earlier in their history, and the Coushatta Tribe expanded from 156 to over 10,000 acres since their casino’s opening.