A Bar Called Charlene’s

The lesbian dive that became a nexus for gay rights in New Orleans

Published: May 31, 2023

Last Updated: December 5, 2023

Newcomb Archives and Nadine Robbert Vorhoff Collection, Newcomb Institute, Tulane University

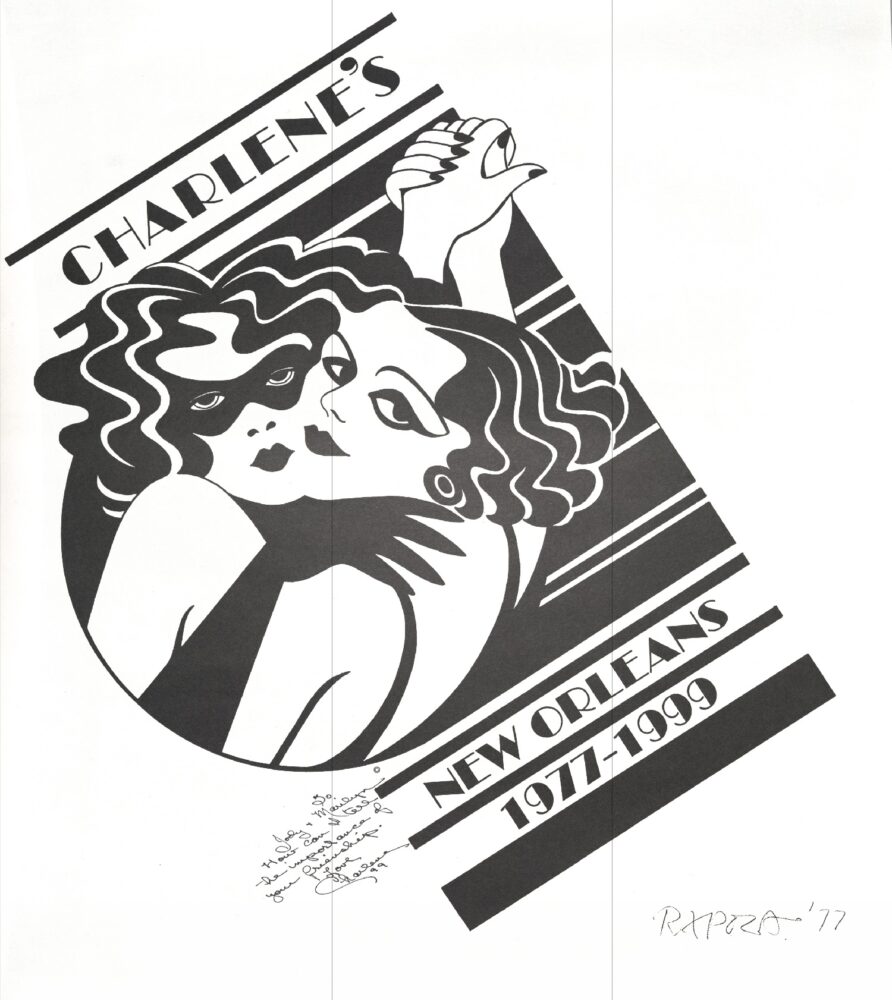

A poster, signed by Schneider, commemorating the bar’s lifespan.

Beneath the halos of streetlamps, the four women leaned on their car hoods and flirted. Emerging from a place of hiding, two male officers of the Fifth District of the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) pounced. They’d been harassing Charlene’s patrons this way for months—emboldened after a series of mass arrests at French Quarter gay bars like Jewel’s Tavern. The officers threw the women against the cars, frisked their bodies, slapped cuffs on their wrists, and placed them under arrest. Their crime? Obstruction of free passage, legalese for blocking a sidewalk. As patrons inside Charlene’s sounded the alarm, the officers noticed three more women—just in from Baton Rouge—walking towards the bar. The officers arrested them for the same sidewalk crime.

Now seven handcuffed women stood in a dehumanizing line outside of Charlene’s. Most of these women weren’t “out” at work. In a time without employment protections for sexual orientation, they would all almost assuredly be fired if the location of their arrests became publicized. Alert to the emergency, Charlene Schneider leapt over her bar and ran outside to intervene. At forty-two years old, Charlene was a short, trim lesbian woman with a dark feathered mullet, dimpled cheeks, and the unmistakable y’at accent of a New Orleanian. Neither butch nor femme, she transcended gay archetypes and rejected bigotry wholesale. She had the gruff voice and moon lines beneath her eyes characteristic of a streetwise smoker, someone who’d seen much from her stoop. “She was open,” remarked her friend and political ally Mark Gonzalez. “And it wasn’t just her look, it was her attitude.”

Trying to understand the charges, Charlene brought out a tape measure to calculate her sidewalk square footage. She asked for a legal definition of “obstruction.” Arriving on the scene, the NOPD Fifth District Commander attempted to rebuff Charlene, saying, “It’s at the discretion of the officers.” Sensing that she wasn’t being taken seriously, Charlene picked up the phone behind her bar and dialed one of her friends in high places. Even before she opened Charlene’s in December 1977, Charlene had begun cultivating political alliances to combat this very form of discrimination.

…she counted seven gay women at the jukebox. “I fell in love with every one of them.”

Charlene knew what it meant to be outed and arrested as a lesbian. Born on August 13, 1940, in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, she moved with her family in early childhood to a house on Magazine Street in New Orleans, and she attended L. E. Rabouin Vocational High School downtown. Charlene was outed by a teacher in 1959, her senior year of high school, after watching her first “girl crush” marry a man. Expelled from school, Charlene ran away from home. Her mother had to personally take her back to Rabouin to get reinstated. Soon after, Charlene went to her first lesbian bar, The Tiger Lounge on Tchoupitoulas Street. When she walked into the place in 1959, she counted seven gay women at the jukebox. “I fell in love with every one of them,” she recalled in a 1983 profile for the New Orleans gay newspaper Impact, relieved to discover that “somebody was gay besides me.”

After graduating, Charlene’s typing skills qualified her for a high-status job, and she worked as a crypto-teletype operator for the contractor Mason-Rust at the NASA Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans East. Due to the sensitive nature of her codework, Charlene applied for, and received, a federal security clearance. For several years, she balanced the discrete halves of her life—by day, a coder and decoder at a facility building stages of the Saturn V rocket; by night, a connoisseur of Quarter lesbian bars like The Village Inn. Then those worlds collided.

“Members of the headquarters special vice squad Saturday reported the arrest of 16 women, a female juvenile and two men from The Village Inn Bar, 345 Dauphine, on various charges of obscenity,” reported the Times-Picayune in August 1964. Charlene had taken her baby sister Diane Schneider, also a lesbian, to The Village Inn to celebrate Diane’s eighteenth birthday. They’d grabbed a pitcher of beer, and Diane was agog, reveling in newfound attention. Then someone called Charlene over to the bar’s pay phone. A lesbian friend, whose dad was a cop, tipped Charlene off that The Village Inn was about to be raided. It all happened faster than Charlene could react: lights, screaming, pushing, handcuffs. Charlene escaped out a side door, but then it dawned on her that Diane wasn’t at her side. Charlene intentionally went back into The Village Inn so she could be apprehended and put in the same paddy wagon as her sister. “She tried to protect Diane,” recalled Linda Tucker, the woman who’d become Charlene’s life partner.

Charlene tried to clarify that her lesbianism wasn’t a blackmail risk because it wasn’t a secret to anyone in her circle.

To limit blowback from the arrest, Charlene gave the false name Charmania Cochran at the police station. But Diane stated her real identity, which tipped off Charlene’s security officer at Michoud—a federal functionary tasked to investigate security risks for NASA. When Charlene showed up at the First District Court to face misdemeanor charges as “Charmania,” that security officer stood in the back. Within minutes, Charlene was handcuffed anew and charged with the felony of making a false statement to police.

When Charlene arrived at work the following day, her boss told her that debriefing agents were flying in from Patterson Air Force Base. Those three federal agents interrogated her for two hours. They threatened her with what would happen if she revealed a single detail of her codework. At the end of the grilling, they yanked Charlene’s security clearance for reason of homosexuality, which they said made her susceptible to blackmail from foreign governments. Charlene tried to clarify that her lesbianism wasn’t a blackmail risk because it wasn’t a secret to anyone in her circle. The explanation disgusted them. As Charlene remembered, “They dismissed me as if I was a dog.”

Charlene’s mind shattered. She refused to leave her apartment. “It’s very hard for gay people to lose their jobs,” she explained to New Orleans historian and gay activist Roberts Batson in 1997. “We tend to be very independent. That fear kept many gay people from going to the bars and made activism so difficult. It was a choice between being outed and a bum with no job or being self-homophobic and successful.” Though her felony charge got dropped, it didn’t resurrect her previous employment, and her car got repossessed. Eventually, Charlene reemerged with a black mark on her resume. She was so humiliated that she only applied to work at gay bars—the very locations that police targeted. In January 1968 Charlene was arrested again while working at Red’s Bar at 940 St. Ferdinand Street. Seven women, including her, were charged with “alleged lesbian activities.” Afterwards, Charlene’s real name appeared in the Times-Picayune.

So when she opened Charlene’s in December 1977, she wanted her bar to be a haven from a world of dangers. “Charlene always said she wanted somewhere where women could be safe,” recalled Linda Tucker. “And that’s why she opened her own bar and used her own name.” Though the décor was spare besides a few booths and a pool table and tile dance floor with cracks down the middle, Charlene’s swiftly garnered a regular crowd. The bar’s art-deco logo of two women, one masked, dancing cheek to cheek with hands clasped seemed to say it all. “It was a comfortable, small bar, and when people started dancing, the place was rocking,” recalled former patron Maxx Sizeler. “I remember how welcome I felt, and I remember how, for the first time in my life, I fit in somewhere.” Fellow patron Valda Lewis likened Charlene’s to the ultimate dive. “There were some mirrors on the walls here and there, and you could basically spit on the floor and nobody would care,” Lewis said, laughing. The eclectic jukebox at Charlene’s was beloved by clientele, with tunes ranging from contemporary Madonna to vintage Fats Domino.

Regulars at Charlene’s got an automatic social life for the price of a beer each night. “We’re a whole support system,” Charlene bragged. In the years when many lesbians were rejected by biological family, Charlene became a mentor figure for “families of choice” as well as lesbian youth. “Charlene was one of the people that you knew would be supportive if you got arrested or even if you were having problems with your girlfriend,” recalled Mark Gonzalez, a gay attorney who Charlene frequently sought out for legal consultations. Resolutely, Charlene guarded patron privacy and held customers to strict “No Fighting, No F******” rules. “I make you a deal: You don’t smoke dope in my bar, and I don’t shoot out your kneecaps!” Charlene joked to Playboy magazine in 1979. To keep “predatory straights” who ogled at lesbians or married couples cruising for threesomes away from clientele, Charlene’s patrons got buzzed in at the front door, which she monitored with an eagle eye.

On February 27, 1978, Charlene’s hosted a political forum for candidates in the Louisiana State Senate District 4 special election, the first in a series of candidate/constituent meetups that continued for the bar’s duration. “When we started to be visibly queer in the political movement, by and large the bar owners didn’t want to have anything to do with us,” recalled Roberts Batson. “Charlene was a notable exception—because she had already been arrested. No one was as visible.” Charlene developed a reputation for imploring patrons to become politically active. “Are you a registered voter?” she’d ask. If a woman answered no, she’d quip, “Then your opinion don’t count for shit.” Determined to link party-centric New Orleans with the national Stonewall legacy of gay politics, Charlene spearheaded a campaign in 1979 with law student Mark Gonzalez and activist Dick O’Connor to bring a political Pride celebration to New Orleans. Brainstorming at the bar, they decided to call the new happening Gay Fest, and it took place just down the street that year at Washington Square Park.

Depending on the day, Charlene’s could feel like a saloon, a cramped dancehall, a music venue, and a debate space all rolled into one. It was a community clearinghouse. It was just the sort of place where lesbians could stop in after work to catch a comedy show from Ellen DeGeneres or drop off a signed civil rights petition. “Ellen was a customer and a young struggling comedienne determined to become famous,” recollected Charlene in an unpublished autobiography. Charlene’s patrons also caught touring musicians from the national circuit of lesbian artists. The summer of 1986, for example, a young singer-songwriter named Melissa Etheridge kicked off a grassroots tour at Charlene’s. Patron Brenda Laura was there that night. “She opened her mouth,” recalled Laura in a recent interview, “and she could have had any woman she wanted.”

Newly official couple Linda Tucker (left) and Charlene Schneider (right) attending a Human Rights Campaign Fund gala to honor Charlene in 1988. Courtesy Linda Tucker.

In 1987 Linda Tucker, head coach of the NCAA female basketball team for Rice University, strolled into Charlene’s. When Tucker accidentally bumped into Charlene that night, they hugged almost involuntarily. “Get her away from me, she fits!” Charlene shouted. That was it. They were together for the next nineteen years. “Charlene was very, very protective of me,” Tucker recalled. “She didn’t want anything to jeopardize my profession.”

For the first few years, Charlene lived in a small apartment in the back of the bar to save on expenses. “Charlene never had any money,” Maxx Sizeler and Linda Tucker both said. “Lesbians just never drink enough to keep a bar afloat,” Sizeler added. Generous nonetheless, Charlene held charity fundraisers such as “Toys for Desire,” an annual Christmas pledge drive that donated presents to children in need; the fundraising party featured, according to Valda Lewis, “a lesbian Santa with a big beard.” Meanwhile, Charlene made outreach to police and government a priority. She joined the Louisiana Lesbian and Gay Political Action Caucus (better known as LAGPAC) and encouraged LAGPAC’s efforts to fundraise for the purchase of bulletproof vests for police officers. She also cheered the creation of a charity softball game between the New Orleans gay community and the NOPD between 1980 and 1981, umpired by New Orleans City Councilmembers like Lambert Boissiere (whose campaign LAGPAC had endorsed). When Ernest “Dutch” Morial, the first Black mayor in New Orleans history, was reelected in 1982, Charlene—an openly lesbian politico—was invited to the inauguration.

These steps towards peaceable relations between gays and the authorities stood at risk on the evening of June 1983, with the arrest of seven patrons outside Charlene’s on surreptitious charges. Treated disrespectfully by the NOPD Fifth District Commander, Charlene called the home number of her good friend—Councilmember Lambert Boissiere. When Boissiere pulled up to Charlene’s in his car, the police backtracked on their sidewalk ruse and said they’d amend the charges. Boissiere exploded. “You just told me that those women were arrested for blocking the sidewalk and open containers, and if there’s going to be anything else on their police report, you’re going to be in trouble with me,” he said. Charlene helped bail out the arrestees, found them hotel rooms, and went with them to their morning hearing. As if by magic, the judge dropped all charges against Charlene’s patrons. Associated records were expunged, and the arrestees’ names didn’t even make the newspaper. Thus did Charlene’s participation in New Orleans politics pay dividends.

Charlene and New Orleans City Councilmember Johnny Jackson on the National Mall at the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987. Courtesy Valda Lewis, LGBT Legacy Project.

As the nationwide lesbian bar scene collapsed on the cusp of the 1990s—squeezed by neighborhood gentrification and then undermined by the advent of email, online chatting, and internet dating—Charlene’s remained an outpost on Elysian Fields, though her landlord kept raising the rent. Bar events like Saints games and Charlene’s birthday, August 13, drew regular crowds. It was at a political meeting at Charlene’s that a young, Black New Orleanian named Larry Bagneris proposed his candidacy for the City Council District C seat; the year was 1989, and Bagneris became the first openly gay candidate to run for local office. In 1991 Charlene hailed the New Orleans City Council’s passage of an anti-discrimination ordinance protecting gays and lesbians. She celebrated at Charlene’s alongside fellow members of LAGPAC, several of whom fought eleven years for the victory.

But when the lease on Charlene’s was up in 1999, she knew she couldn’t manage the next rent hike. She made “Last Call at Charlene’s” a formal adieu, a celebration of more than twenty years serving the community. Newspapers reported the sendoff, and on February 20, Charlene’s was wall-to-wall packed with well-wishers and officials. “It’s very difficult to let something good go away, but that’s what happened at New Orleans’s oldest Lesbian bar,” elegized the gay New Orleans newspaper Ambush. (New Orleans’s last lesbian bar, Rubyfruit Jungle, would close in 2012.)

Charlene retired to Bay St. Louis with her partner Linda. She died of cancer just a few years later, on December 3, 2006. She was sixty-six. A former New Orleans Councilmember and close friend named Johnny Jackson Jr. spoke the eulogy at her funeral, and a portion of her ashes were interred at the home of fellow LAGPAC member Stewart Butler in a private memorial for New Orleans activists. The following year, Linda Tucker paid to install a plaque at the historic site of Charlene’s Bar on Elysian Fields. It reads, “Let the work I have done speak for me.”

Robert W. Fieseler is a National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association “Journalist of the Year” and the acclaimed nonfiction author of Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation—winner of the Edgar Award and the Louisiana Literary Award, shortlisted for the Saroyan International Prize for Writing. Fieseler is currently working on his second queer history book. He lives with his husband in New Orleans.

Published June 1, 2023.