The Formation of Reggie Adams

The story of the lone known Black victim of the 1973 Up Stairs Lounge tragedy

Published: December 1, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Johnny Townsend

Adams and friends at the Up Stairs Lounge.

These vows were the culmination of a two-year spiritual audition as Jesuit novices in the arduous eight- to seventeen-year “formation” process that could either end in dismissal or becoming a priest. Their novice class, which began as a cohort of ten in the summer of Woodstock, was now winnowed down to six. Their spiritual training, held in a bright white building called St. Charles College rising from swamps near Bayou Belleview, represented the Catholic equivalent of military bootcamp—intense and often solitary, with “particular friendships” among classmates discouraged.

Five novices took vows that Sunday and received elevation to the status of Jesuit “scholastic.” One, the only Black novice in the group, was not present. Though superiors made assurances that this wasn’t out of order, with three novices delaying vows the prior year, a neophyte named John Reine, who’d just joined the Jesuits, noticed the absence. Something had kept that young man, twenty-two-year-old Reginald “Reggie” Adams from Dallas, from making that same promise. Instead, this Black novice had been stealthily sent ahead of his class to studies at Loyola University in New Orleans.

According to his former lovers and friends, with whom I conducted personal interviews from 2014 to 2021, Reggie the aspirant priest became spiritually and sexually unleashed shortly after arriving in the Big Easy. Though he resided as a scholarship student in the Jesuit house of studies, called Druhan Residence, at 6318 Freret Street, he grew an Afro and ditched the novice uniform for bell-bottoms and printed shirts. Catching the St. Charles Streetcar from Loyola towards the French Quarter, Reggie explored the city’s gay underworld.

On Bourbon Street, he encountered convoluted racial codes wherein gay Black men were not permitted inside the same gay bars where white gay men flocked. At Café Lafitte in Exile, when a patron deemed to be “too Black” approached the doors, bouncers would ask that man to produce up to four forms of ID to gain admittance, an escalating ruse meant to deny any gay Black patron equal access.

But on Iberville Street, an extralegal borderland on the edge of the French Quarter, Reggie found relaxed rules and met others like himself. Gay men who often wore wedding rings and identified as “bachelors” cautiously pursued one another in violation of state law forbidding “crimes against nature” and local ordinances suppressing “sex deviates.” Reggie frequented a second-story Black gay bar on the corner of Royal Street called the Safari Lounge and a popular, mixed-race gay bar on the corner of Chartres Street called the Up Stairs Lounge.

At Café Lafitte in Exile, when a patron deemed to be “too Black” approached the doors, bouncers would ask that man to produce up to four forms of ID to gain admittance.

The come-one, come-all atmosphere of the Up Stairs Lounge particularly appealed to Reggie, as he was accustomed to interracial environments from his time around progressive Catholics in Dallas, and he found the entrenched segregation of the Deep South to be jarring. Around the white baby grand piano of the Up Stairs Lounge, working-class gay patrons crooned an anthemic song, “United We Stand” by Brotherhood of Man, that summed up their egalitarian beliefs. The chorus went, “United we stand, divided we fall.”

It was at the Up Stairs Lounge that Reggie was introduced to a white Mormon patron born with the last name Soleto, who was then experimenting with various female personae. She uses the name Regina today and openly identifies as transgender, but in 1970s New Orleans, neither the concept of gender identity nor the word “trans-gender,” as then spelled by the few national activists who used the term, were well understood. Reggie found this young woman ravishing and took her home on the St. Charles Streetcar towards Druhan Residence.

“First time I went there, I didn’t know where I was going,” Regina recalled, laughing. “And I saw the big front of Loyola, and I said, ‘Oh, are you living at school?’ and he said, ‘No, I live at the novitiate house.’ So I said, ‘Okaaaay.’” They spent the night in Reggie’s private room, where she said his small cot squeaked like a calliope.

In the morning, they washed in the common showers and remained so giddy that they accidentally bumped into Reggie’s house superior, Father George Francis Wiltz. Brazenly, but with some chivalry, Reggie introduced his Jesuit superior to his new bedmate.

Reginald Eugene Adams was born on May 31, 1949, in Dallas, Texas. So humble were his origins that the Texas Department of Health misspelled his name “Rugenal” in state birth records. A bespectacled teen raised in poverty near the West Dallas Housing Projects, Reggie displayed enough academic promise to be recruited early by the Jesuit order of Catholic intellectuals.In 1967, Reggie was accepted as a scholarship transfer student to Jesuit High School in Dallas, a flagship college preparatory institution. Tossed into such fertile educational terrain, Reggie thrived as a member of the History Club and the Glee Club, where he sang baritone. He drove a tiny French car called a Simca that barely contained his long, skinny legs and spent off hours at a public library housed in a strip mall across the street from a lead smelter facility.

Reggie played oboe in the school band and became an aficionado of classical music, a personal favorite being Handel’s “Water Music.” Reggie also found adolescent love with a blond named Marc Schmitz, who lived in the housing projects and for whom Reggie secured a scholarship to Jesuit High. “He could be an intense guy, not in an intimidating way, but he was brilliant, soft-spoken,” remembered Schmitz. “He would push people, question them, but he wasn’t confrontational or aggressive. He was kind of towering, physically and intellectually.” To explain why he never dated women his age, Reggie often claimed to have a girlfriend in France.

Graduating in 1968, Reggie attended the University of Dallas, a Catholic institution, for a year while also serving as a substitute teacher at St. Mary of Carmel, a Catholic elementary school near the housing projects, and a counselor at events called “happenings,” or weekend retreats for Catholic youth.

On August 14, 1969, Reggie formally entered the Jesuit order at St. Charles College in Grand Coteau, Louisiana. He embraced a life of celibacy and proudly began signing his name “Reginald Adams, N.S.J.,” the abbreviation meaning “Novice, Society of Jesus.” Reggie’s novitiate occurred during a conservative holdover period post–Second Vatican Council, an era of cautious hopes for reconciliation between an ancient Church and the modern world. Jesuits took pride in their “formation” process lasting years longer than the ordinary seminary, and the set of exercises Reggie underwent were among the most rigorous internal spiritual work that a Catholic can experience. As a novice in Grand Coteau at that time, who asked not to be identified for fear of discipline from Jesuit superiors, described, “To be in formation was a very individual, at many times isolated experience for novices. Your own sense of vocation, your interior life, your joys and your struggles, those were meant to be shared with you, God, and your Novice Master.”

At the time, Jesuit superiors warned against strong emotional bonds that could develop between novices and policed them as “particular friendships.” Novices were supposed to be friendly with all people but not friends per se with anyone specific. According to novices of that era, if you sat with the same person at meals more than four times in a row, you got called in and punished. The twofold concern was that “particular friendships” might blossom into unchristian favoritism, at best, or homosexuality, at worst.

Never the athlete, Reggie eschewed playing basketball or handball with his novice class for games of chess, studying in the novice library, or enjoying the shade of one of the numerous live oak trees on the property. “Reggie was very well liked,” the fellow novice told me by phone. “He was always very friendly. He was kind of quiet . . . because novices didn’t share what was going on inside.”

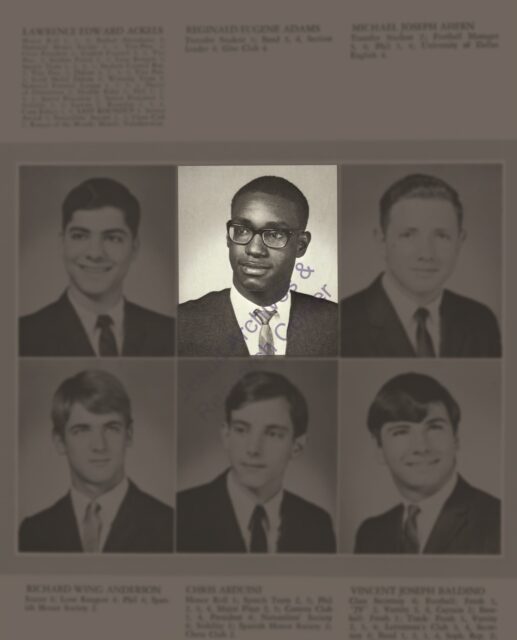

Adams in The Last Roundup ‘68, the yearbook of the Jesuit High School of Dallas. Robert W. Fieseler.

In his two years at Grand Coteau, Reggie slept in a private cubicle nestled in a third-floor dormitory room the size of a basketball court. Overhead intake fans provided the only relief from the heat, sucking wind from the Cajun Prairie through the open windows. Reggie wore black pants and white shirts, with black ties on special occasions, all of which he hung in a small locker. So humid were the environs that when novices hung their worn pants up at night, they’d find mildew in the lining the next morning.

In January 1970, during his first year of novitiate, Reggie underwent what was called the “Long Retreat,” thirty days of silent reflection during which he tested his desire for priesthood and performed a series of spiritual exercises modeled by Saint Ignatius of Loyola. Besides a break on every seventh day, any talking was strictly limited to one daily conference with the Master of Novices. That Jesuit superior during Reggie’s tenure was Father Robert “Bobby” Rimes, a former college football player who, years before the national fitness craze, jogged every morning.

During the Long Retreat, it wasn’t uncommon for young men to make the most vulnerable, unguarded confessions to their Novice Master. Some quit. Some shattered mentally. “There were always stories of suddenly finding that somebody had been sent home,” Reine, a who underwent the Long Retreat in 1971, recalled. “Sometimes there would be an explanation, and sometimes, you were just led to think it’s been taken care of.”

Although it’s unknown if Reggie ever came out to Rimes, John Reine did make the decision to formally come out as homosexual to Rimes during his Long Retreat. “There came a point when I just realized that God wouldn’t want me to try this at the cost of not being honest,” Reine explained. Reine entered the conference thinking, “Are they going to freak?” and spelled out his sexual feelings for other men explicitly. Reine recalled Rimes responding with something to the effect of, “Alright, I’m going to ask you to shelve this issue because this issue by itself is not what the retreat is about; it will not tell me, it will not tell you whether or not this might be the life for you.” Reine left without feeling his confession had altered much of anything.

“If someone told Bobby Rimes he was homosexual, but not practicing, Bobby would have no problem at all,” agreed a novice in Reggie’s class, who maintains a position within the order and asked not to be identified, to avoid having honest words “thrown in my face,” as he put it. “If someone confessed to having a homosexual lover,” Reggie’s classmate continued, “I’m fairly certain he would advise the same as to someone in a heterosexual affair: Cool it down, leave it behind, remember you made a vow against this.” Father Henry Joubert, a reform-minded Jesuit serving as an assistant to Rimes from 1969 to 1971, held the alternate view that God doesn’t condemn loving actions, Reggie’s former classmate told me. Strikingly, around the same time Reggie didn’t take vows, Joubert reportedly left the priesthood and married a former nun.

Racial tension marked Reggie’s time in Grand Coteau. Jesuit High School in Dallas had been integrated since 1955, but when Reggie arrived at St. Charles College in 1969, Grand Coteau had only just elected what the Lafayette newspaper the Daily Advertiser reported as “the first Negro to win a mayor’s seat in a Louisiana town of biracial population since Reconstruction.” The Confederate battle flag still flew above courthouses statewide. On August 2, 1970, the Daily Advertiser reported a “cross was found burning in Grand Coteau at 3 a.m. Sunday” just as local Jesuits made plans to integrate their two parishes, Sacred Heart for whites and Christ the King for Blacks.

“I will never forget waking up one night, and I looked out and heard voices, and the Ku Klux Klan was burning a cross on the corner of our seminary,” the novice in Grand Coteau at that time told me. “I can only imagine with a certain amount of pain what Reggie was experiencing, what he was feeling, what he was thinking. And really not having anyone to share that with. I mean, we never talked about it . . . And the next morning at breakfast, a word wasn’t spoken.” As recently as this year, that local parish in Grand Coteau has refuted the idea of such Klan activity. “There was No local klan [sic]. There were no newspaper articles,” responded church administrative assistant Mary Ann Matte to a July 2021 email request.

During his first year in Grand Coteau, the only clergy of color Reggie worked with was a Catholic nun named Sister Jane Frances. Frances ran a segregated mission school for children of rural Black farmers in nearby Bellevue. According to John Reine, mentioning Reggie would bring a glimmer of joy to the sister’s eye. During Reggie’s second year, a college-educated Black intellectual with a flair for languages named Douglas Hypolite joined the order, but he and Reggie did not become confidantes.

In 1971, Sacred Heart and Christ the King churches formally integrated, eventually being renamed Saint Charles Borromeo. They consolidated parishes around the larger, ornate cathedral of the formerly all-white congregation. About this time, Reggie took on a level of quiet intensity that shook younger novices. “He just kind of frightened me, not that he meant to, but as I look back on it as an adult, I kind of feel like there was anger there that would just come out,” recalled Father Francis Huete, then a first-year novice.

Such were circumstances in 1971 under which Novice Master Bobby Rimes sent Reggie without vows to New Orleans, where Reggie wasted little time finding love at the Up Stairs Lounge. It was Reggie who gave his new partner the name “Regina,” Latin for “queen,” as Reggie often called Regina his queen. So Regina was known from that day forward. Planning to introduce her to family and fellow Jesuits, Reggie confessed to Regina the source of his strife. “He had conflict with being gay and being a priest,” explained Regina. “I don’t know why. Because I’ve met several gay priests . . . But to Reggie, a vow really meant something.”

Regina grew up in Metairie and studied in the Mormon seminary. At twenty years of age, she was preparing for a multiyear mission to China. “I was looking forward to it until I met Reggie,” she admitted. They stared at a spiritual and logistical crossroads. He hadn’t taken his vows, and she hadn’t gone on her mission. “I got my letter to get ready to go on my mission,” she remembered, “and I showed it to him and told him, ‘If I go, I’ll be gone for two years,’ and he says, ‘I really don’t want you to go.’” In tears, they confessed their love.

So Reggie left the priesthood. And Regina declined her mission—tantamount to exiting the Mormon faith. Within six weeks of their meeting, they’d rejected the only worlds they knew to form a tenuous new one together. Even gay friends at the Up Stairs Lounge recognized Reggie and Regina as something truly original. No one they knew shared a love like theirs, on which they could model a future. Regina gave Reggie her high school class ring, which he wore on his left hand as if they’d gotten engaged.

It must be noted that Reggie didn’t exit from the Jesuit order in shame. At one point bringing Regina to Grand Coteau, Reggie conferred with Novice Master Bobby Rimes and made clear that he was being called to a different life. Persuasive and well-respected, Reggie left the Jesuits on remarkably friendly terms. Although his formal “dismissal” from the order occurred in April 1972, Reggie continued to receive family mail through that fall at Druhan Residence, where former Jesuit housemates kept his contact details.

No longer pursuing a path to priesthood, Reggie lost his scholarship to Loyola and moved out of the novice house with just a few articles of clothing to his name. He settled with Regina in a Julia Street flophouse, where they filled their small room with flowers and plants. Maintaining his religious devotion, Reggie joined a local branch of the Metropolitan Community Church, a radical gay-affirming Christian congregation that often met in the back theater hall of the Up Stairs Lounge. When Reggie clasped his hands in prayer during services, Regina’s high school ring often caught the light and gleamed, according to fellow Metropolitan Community Church member Henry Kubicki.

Regina got a job at the parking garage across the street from the Up Stairs Lounge, and Reggie took a furniture sales gig, which gave them the budget to afford an apartment in the French Quarter, at 1017 Conti Street. They spent the holidays with Regina’s family in suburban Metairie, according to Up Stairs Lounge scholar Johnny Townsend, and visited Dallas the following summer. There, Reggie introduced Regina to “Ma’ Dear,” Reggie’s much beloved mother Florene Clark Washington, who responded graciously when Reggie informed her that he and Regina planned to have a commitment ceremony in August 1973.

Balancing newfound love with financial realities, Reggie and Regina’s weekday lives in New Orleans became jampacked with opposite work schedules, but they always saved Sunday nights for each other at the Up Stairs Lounge, where they embraced openly in a safe space. By May 1973, Regina had tired of the racial and gender discrimination in the French Quarter bar scene. “They had a sign on the door at Lafitte’s,” remembered Regina. “It said, ‘No Blacks, No Fems, No Women.’”

Regina dared to sneak Reggie past a friendly doorman into Café Lafitte in Exile during the daytime. “He was the first Black man I ever saw drink in Lafitte’s,” recalled Regina. “And they only let him in because he was with me.” It was a personal victory for the trailblazing couple: raising a glass in New Orleans’s oldest gay bar.

On the night of June 24, 1973, a typical summer Sunday on Iberville Street, Regina left Reggie chatting near the grand piano of the Up Stairs Lounge. She needed to dash to their apartment to retrieve a checkbook to pay for dinner. Earlier in the evening, a drunken patron named Rodger Dale Nunez had been violently ejected from the bar, threatening to burn the establishment, but few in the Up Stairs Lounge paid any mind to the incident.Reggie had only just started his scotch and soda when Regina got up to run the errand. She insisted he stay. Around 7:45 p.m., they pecked and parted with “I love you,” and she ran down the staircase that served as the bar’s sole entrance and exit for the public. Regina strolled to their apartment and back. She was gone for less than twenty minutes, during which someone emptied a can of lighter fluid in that very stairwell and produced a spark.

A taxi buzzer rang inside the Up Stairs Lounge, and when someone opened the door to check downstairs, flames met oxygen and fuel. A fireball exploded, ripping forty-four feet across the main room. In the chaos that ensued, Reggie became pinned to the floor near the bar’s far windows, which were sealed with iron bars as a safety measure approved by fire inspectors; reporting by the Associated Press later confirmed that those inspectors hadn’t visited the bar in more than two years. As smoke billowed and milliseconds ticked, he suffered third and fourth degree burns across ninety-five percent of his body surface. Twenty-four-year-old Reginald Eugene Adams closed his eyes and perished, just as firefighters reached the nearby intersection of Chartres and Iberville Streets within 120 seconds of the first alarm. “I call it the cobra . . . superheated gas that will knock you unconscious in just a couple of whiffs,” explained New Orleans Fire Superintendent William McCrossen to the Daily Record, a small New Orleans newspaper. “The tiger . . . fire . . . will finish you off.”

Minutes later, Regina walked the final block down Iberville and witnessed the fallout herself. She shouted for Reggie among milling onlookers as firefighters doused the flames. Regina kept thinking she saw Reggie emerge from the crowd, but it would only be a stranger’s face. Frantically, she rushed to Charity Hospital, when she couldn’t find Reggie among the survivors. She didn’t venture down into the morgue because, in her words, “There was nothing left to ID.”

Regina went home to their apartment on Conti Street and descended into a state of near catatonia. Though firefighters extinguished the blaze by 8:12 p.m., the Orleans Parish Coroner would have to pry Reggie’s remains from what he called a “mass of death,” a pile of seventeen bodies stacked one upon the next near the window bars. It was the deadliest fire on record in New Orleans history, claiming twenty-nine lives in a span of minutes. Three more who escaped the flames suffered agonizing deaths in the Charity Hospital burn ward.

Front-page stories of the fire in the next morning’s Times-Picayune didn’t use the word “homosexual” to describe the Up Stairs Lounge patrons. Newspaper editors of the era tended to police and expunge the radical word “gay,” because it associated joy with a criminal lifestyle. The Louisiana Weekly, New Orleans’s Black newspaper, reported, “It is not known if any of the victims are black, but a number of black patrons had been known to frequent the bar called ‘The Upstairs.’” After it became widely known that the Up Stairs Lounge served homosexual patrons, no follow-up stories appeared in that newspaper, nor in national Black publications like the Chicago Daily Defender.

Reggie would be tentatively identified among the Up Stairs Lounge dead through witness statements by that Wednesday, June 27. That Thursday, detectives visited Regina at her apartment, where she’d been laying out Reggie’s clothes on the bed each morning in denial of his passing. Fighting through her grief, she gave a statement to police. But the coroner struggled to forensically process the full scope of death, ultimately thirty-two fatalities. Many families hesitated to step forward to help identify the Up Stairs Lounge victims because of associated stigma towards homosexuality. One local family who did step forward, that of fire victim Clarence McCloskey, were subsequently denied a Catholic funeral for their loved one by New Orleans parish Saint Rose de Lima, according to McCloskey’s sister Rose Little.

As smoke billowed and milliseconds ticked, he suffered third and fourth degree burns across ninety-five percent of his body surface. Twenty-four-year-old Reginald Eugene Adams closed his eyes and perished.

Flames in the bar had been scorching enough to char much of Reggie’s external skin tissue, which likely led investigators to mistakenly identify him as “an adult white male” in a written report. But the coroner did ultimately mark his body as “N,” shorthand for the 1970s legal term “Negro.” Ultimately, it wasn’t Black civil rights constituencies or gay activists or his lover or even his family who stepped forward to enable Reggie’s positive identification. “It was the Jesuits,” Regina asserted. “Through his dental records, they found out who he was, and it was the Church that had the dental records.”

Although Reggie’s official Jesuit file remains sealed from public review, several priests of that era recount how New Orleans authorities contacted Father Joseph Doyle, the house superior in 1973 at Loyola’s Druhan Residence, for Reggie’s medical and dental files. According to these current and former Jesuits, Doyle acquired Reggie’s records and facilitated their transfer. “Joe was very moved by having to go through this experience,” the fellow novice, who personally spoke to Doyle about it, told me by phone. “He was shocked and saddened. And having to secure the dental records was something that brought it home.”

Attesting to Doyle’s character, Father Francis Huete said, “If somebody needed to go down there to identify and he was asked, he would have done it.” (Doyle passed away in 2008.) Word about Reggie spread fast among the Jesuits. Members of his former novice class were distraught that he died, as well as surprised to learn that he was gay. None had suspected. John Reine was sitting at the lunch table in Grand Coteau with Father Bobby Rimes when the Novice Master learned of the death. “I got some really bad news,” Rimes told the group. That year, Reine would take his vows and continue on with formation; eventually Reine left the Jesuits to openly embrace what members of his former order called an “alternative lifestyle.”

Reggie’s positive ID through the Jesuits spared him the fate of fellow Up Stairs Lounge victims who went unidentified or whose families could not be easily located. Bodies that went unclaimed were dropped into unmarked graves in a remote potter’s field called Resthaven in New Orleans East; the burial records were subsequently lost. Nearly half a century later, the family of Up Stairs Lounge victim Ferris LeBlanc is still fighting Louisiana bureaucracies to locate the gravesite and exhume the body.

Despite the documented presence of Catholic priests providing “conditional absolution” over charred bodies at the Up Stairs Lounge, Catholic chaplains ministering to fire survivors at Charity Hospital, and Jesuits producing dental records to identify Reginald Adams, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans formally claimed they had no knowledge of the fire to gay activists and community members asking for public comment in the days that followed. They refused St. Louis Cathedral as an Up Stairs Lounge memorial site and declined to address the fire as a human rights issue. A spokesperson for the Archdiocesan Human Relations Committee told a local journalist that “they see no reason to issue any sort of statement on the matter.” New Orleans Mayor Moon Landrieu made no statement about the fire until July 11, and Archbishop Philip Hannan waited until July 19 to acknowledge the tragedy in a little-read column of the archdiocesan newspaper. “The report and opinion of the fire chief that arson could have been or probably was involved,” Hannan wrote, “makes all the more deplorable this holocaust.” That August, New Orleans police would prematurely close the investigation without questioning the chief suspect, Rodger Dale Nunez, and declared the fire to be of “undetermined origin.” Nunez died by suicide a year later.

Reggie’s mother Florene Clark Washington traveled from Dallas in early July 1973 to bring home the remains of her son. According to a death notice posted in the Dallas Morning News, “seminary student” Reginald Eugene Adams received a funeral at St. James Catholic Church in Dallas on Wednesday, July 11. So hurried were the arrangements that the obituary was posted on the same day as the service, giving mourners little notice. Within hours of this memorial, Reggie entered the ground at Calvary Hill Cemetery with Regina’s high school ring seared to what remained of his left index finger.

Several priests from Jesuit High School in Dallas were able to attend Reggie’s funeral, and his name continues to be included among deceased graduates during their annual Mass for alumni. Regina, however, was not notified of the funeral and received no further contact from the family. In 1980, she formally changed her surname to Adams in honor of the man she once intended to marry. That way, she could always be his “queen.”

Regina Adams lived for years with the paralyzing fear that if she ever loved again, her partner would die in an instant. Though she’s since reinvented herself several times over and evolved into one of New Orleans’s most celebrated entertainers—receiving a host of queer community honors such as Grand Marshal of Southern Decadence and Transgender Person of the Year—Regina has never returned to Dallas since her first trip with Reggie. As such, she hasn’t been able to bring herself to visit Reggie’s grave.

I went alone. On Sunday, July 17, 2021, I crossed the lawn of St. Theresa plot in Calvary Hill Cemetery to the place on the map marked “Adams”: lot number twenty-one, space two. There in the shadow of a tall pine, beside the marker for the family Smith, was a flat patch of grass. Bearing nothing but the beautiful uncut hair of a grave, as Walt Whitman put it.Given his family’s financial struggles and the sudden nature of the burial, one has to believe that someone who loved Reggie intended to give him a gravestone but was never able to do so. Thus rests Reggie, former Jesuit and only known Black victim of the Up Stairs Lounge fire, in privacy—his view unobstructed, I’d like to think, beneath the path of aircraft descending from the heavens to Love Field.

Robert W. Fieseler is a National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association “Journalist of the Year” and the acclaimed nonfiction author of Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation—winner of the Edgar Award and the Louisiana Literary Award, shortlisted for the Saroyan International Prize for Writing. Fieseler is currently working on his second queer history book. He lives with his husband in New Orleans.