A Priest on the Color Line

In New Orleans and Breaux Bridge, Father Antoine Borias navigated race and saved souls

Published: November 30, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

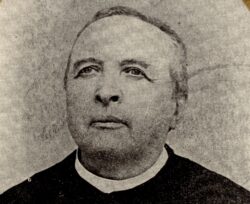

Archdiocese of New Orleans Archives

Undated photo of Father Antoine Borias.

It’s no surprise, then, that church records show the Herrimans attending St. Augustine more than any other church. From the 1840s through the 1890s, the Archdiocese of New Orleans noted that the family gathered at St. Augustine to celebrate numerous baptisms and other blessed events. But on Sunday morning, October 17, 1880, instead of walking to St. Augustine, the Herrimans turned in the opposite direction and headed toward the corner of Claiborne Avenue and Annette Street. There, at Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church, they presented George Joseph Herriman for the sacrament of baptism.

The infant baptized that day would grow up to become the celebrated cartoonist George Herriman, who brought very Catholic stories of love and hate and transgression and punishment into his famed comic strip Krazy Kat. But this isn’t his story—it’s the story of the priest who baptized him, who was the reason why the family broke with tradition that day to attend Sacred Heart.

That priest’s name was Antoine Borias, and he was pastor at Sacred Heart. Borias was a Paris-born, fifty-two-year-old priest with a round face and thinning hair, a cassocked adventurer who had already lost his health and nearly his life on more than one occasion as he tempted the swamps and plains of south Louisiana and east Texas. When Borias joined other young French priests in answering the call to travel to the American South, he would find himself impelled to do more than save souls. He would have to mark his own territory on the shifting and violent racial landscape of his new home.

Borias responded to this challenge by welcoming Black Catholics into his church in New Orleans and, when he lost that church, into a school he founded in Breaux Bridge. For this, the Herriman family would trust him with their first son.

Borias would learn, however, that not everybody in the community would be so appreciative.

Just as mid-nineteenth-century dime novels charged the American imagination with lurid tales of taming a frontier, so too did stories of wilderness adventures reach young Catholic men in France eager to encounter both new lands and new souls.The names of these accounts, “Annals of the Propagation of the Faith,” give little indication of the lurid content: tales of beauties and savages in an open, wild land; marauders and destruction and redemption all on a dusty trail. The stories found a home in the fantasy lives of young French priests. “They were attracted to North America because of tales of adventure and martyrdom, an imagining of adventure,” said Michael Pasquier, whose book Fathers on the Frontier explores the lives and beliefs of nineteenth-century French missionaries. “They’re sometimes anthropological, making observations about these strange people. It becomes impressionable to young men thinking of the priesthood.”

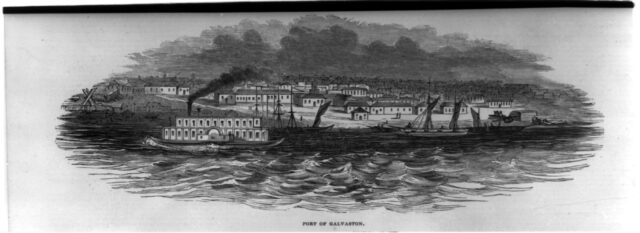

One of these young men was Antoine Borias. When he was twenty-five, he found himself in Galveston, Texas. It was Christmas Eve, 1853, and Borias was one of more than seventy priests serving the Archdiocese of New Orleans, which then stretched into Texas. But Borias’s adventure didn’t begin well, and it wouldn’t get much better. He arrived with a chest ailment and spent that Christmas in bed. New Orleans Archbishop Antoine Blanc and Galveston Bishop Jean-Marie Odin—who themselves both arrived as French missionary priests—tried to figure out what to do with their new recruit. They settled on sending him to Beaumont, where he was charged to “take care of quite a number of creole families,” according to Church correspondence.

Texas was a rough and ready place, and priests didn’t get a pass from troublemakers. In Brownsville, thieves had broken into the church and stolen the ciborium, which was found the next day with “the Sacred Species thrown here and there in the mud,” according to reports. Borias embraced his Texas mission, promising to build chapels and schools. Yet within a year, there were reports that he was beaten up and left for dead near the town of Goliad, and that near San Patricio he only escaped gunfire because he had a faster horse. By 1866, Borias was back in France, in poor health and begging to be reassigned to Louisiana. He complained that his attempts to learn English weren’t successful, and noted that his French would serve him better in New Orleans. Plus there were those days when he was shot at and left for dead.

His pleas were heard. Borias returned to the United States and began serving in New Orleans. Yet this too began badly, for he soon contracted yellow fever. Still, he must have consoled himself that at least it wasn’t Texas.

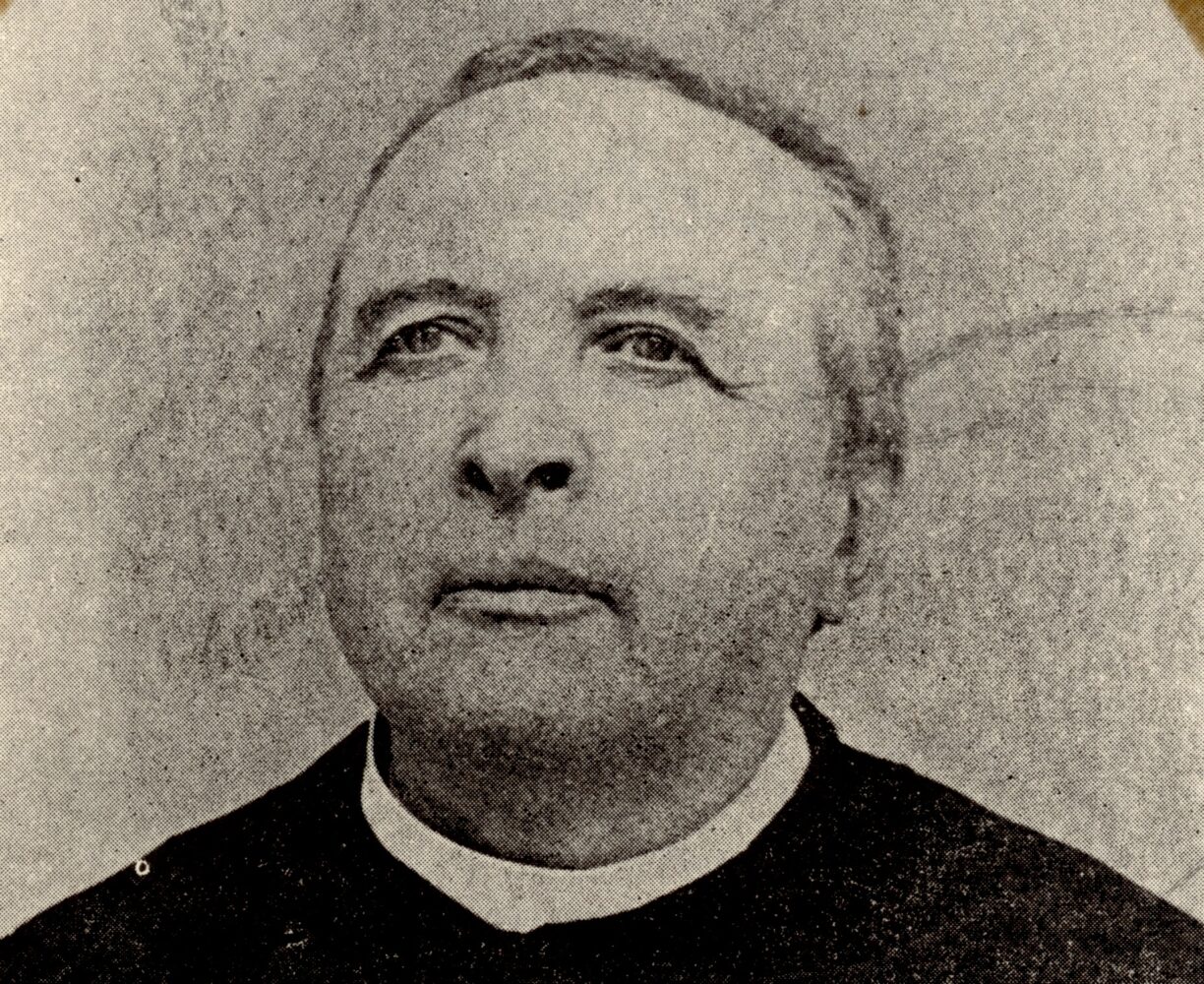

The 1870 census lists Antoine Borias living in New Orleans’s Sixth Ward with two other priests, both from France. Also in the household are two children, described as servants. Adelaide Meilleur is sixteen and her sister Marie is seven. They are Black and, according to the census report, neither could read nor write.There is no further information about the two girls. The census does not reveal if they had been enslaved until abolition, just six years earlier, or speak of the fate of their parents. This glimpse of the two Meilleur children living and working in a household with three French priests is another reminder of the complicated and compromised relationship between the Catholic Church and the institution of slavery. This relationship was not part of the missionary adventure tales that first lured French priests to the United States. Priests like Antoine Borias would have learned about it after they arrived.

1870 census showing Borias living in New Orleans’s Sixth Ward. National Archives and Records Administration

When they did set foot in their new homeland, French priests found themselves caught between anti-slavery edicts from superiors in France and the laws and customs of the South and the Confederacy. “They’re having to deal with the fact that their brother priests in France are for abolition, and now they adjust their understanding of Catholicism to accommodate a slave society,” Pasquier said. “It wasn’t a tough sell. They embraced the institution of slavery pretty much wholeheartedly as a body of priests, and benefited from it.”

In 1852—right around the time that Borias likely set sail from French shores—New Orleans Archbishop Antoine Blanc issued the first official word on slavery from a local cleric. His pastoral letter on “Slavery and True Freedom” argued for obedience to laws. Catholics, Blanc argued, should be more worried about shackles on souls than shackles on bodies.

One priest would famously reject that letter. Also from France, Claude Paschal Maistre arrived in Louisiana in 1855. He would serve as minister to the Native Guard of free people of color who took up arms against the Confederacy, and “became the only Catholic cleric in New Orleans to publicly advocate abolition and equal rights for blacks,” writes Stephen J. Ochs in A Black Patriot and a White Priest, his biography of Maistre and Black Civil War hero André Cailloux. Most famously, Maistre defied his superiors’ orders in 1863, when he presided over a grand public funeral for Cailloux, who had died in battle.

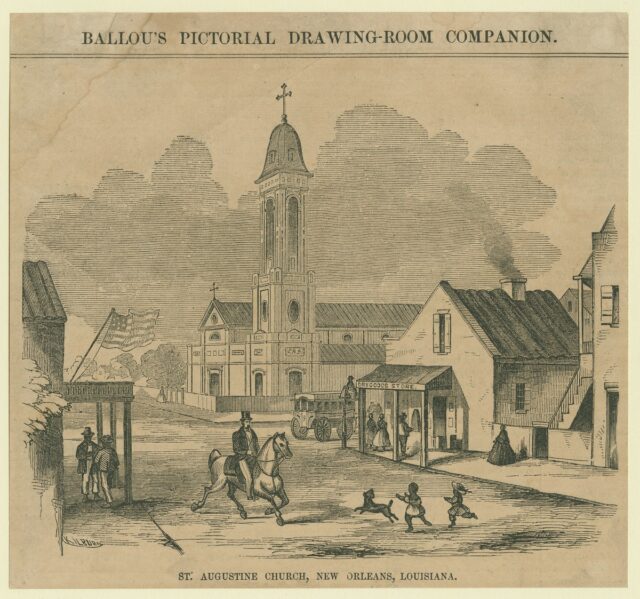

There are no records of Borias being so brave or outspoken. Yet when he arrived in New Orleans, his first position would be at St. Augustine Church in Tremé, known then and now as a center of interracial worship. “St. Augustine Parish was a bastion of Black Catholic life, and it would be one of the real holdouts for preserving Black Catholic participation,” said James Bennett, who chronicled churches during and after the Confederacy in his history Religion and the Rise of Jim Crow in New Orleans.

…he was beaten up and left for dead near the town of Goliad, and near San Patricio he only escaped gunfire because he had a faster horse.

Despite its tolerant—even enthusiastic—attitude toward slavery, the Catholic Church in New Orleans was also known for welcoming both Black and white worshippers to Mass. Travelers to the city frequently commented on the unusual sight. “Never had I seen such a mixture of conditions and colors,” one visitor reported in 1845 after visiting St. Louis Cathedral, in a letter cited by Bennett. When Antoine Borias first stood at St. Augustine’s altar, he looked over a congregation that was mixed in every possible way: color, social status, and legal freedom. Free people of color contributed to the construction of the church’s pews, which sat alongside pews donated by white parishioners. Worshippers who were enslaved sat in smaller pews on the side.

By 1868, the war had ended and Borias had apparently made a full recovery from both his injuries in Texas and his bout of yellow fever in Louisiana. “Rarely have we harkened to language as fervid or tones as deep and pathetic,” the Morning Star and Catholic Messenger rhapsodized after witnessing a Borias sermon on Sunday morning. “He discoursed as if God inspired, and the honey that came, as it were, dripping from his lips, was sweeter and purer than that distilled from Hybla’s Mount.”

Three years later, Borias would throw himself into opening Sacred Heart. The parishioners would be mostly Black and they were mostly poor, so Borias announced his plan to raise funds from across the city. Held at the Blaffer Building—then a popular site for events, located on Canal Street near Rampart—a series of balls featured a “host of our charming young creole ladies,” reported the Morning Star and Catholic Messenger.

This engraving from the January 4, 1845, edition of the London Illustrated News shows Galveston much as Borias would have encountered it. Library of Congress

The fundraiser appears to have been a success. On September 11, 1871, the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin reported the ceremonial laying of a cornerstone at Annette and Claiborne. The church was projected to cost twenty thousand dollars, with Gothic windows and a hundred-foot steeple “in striking contrast with the low roofed cottages of the vicinity.”

Sacred Heart became a vital parish, energized by Black-led organizations that filled the nearby streets during Jubilee processions to nearby churches. According to reports, Borias led the marches, followed by children, bankers, ladies, gentlemen, and the local chapter of the St. Peter’s Total Abstinence Society. On another day, the church was “crowded almost to suffocation,” complete with choirs, ringing bells, and a six-hundred-strong congregation. When Borias visited France to check on his aging parents, he returned to his congregation with tears in his eyes, overcome with emotion to be back at Sacred Heart. “Considering the poverty of the congregation, which is composed principally of colored persons, the zealous pastor, Father Borias, has wrought wonders since he undertook the building of the church some ten years ago,” reported the Morning Star and Catholic Messenger in 1878.

And then, just a few years later, it was over. It’s not certain why Borias left—or was removed from—Sacred Heart. Although surviving church letters don’t reveal the reasons for the conflict, the acrimony is made clear. Borias even went over the heads of his Louisiana superiors and contacted Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni in Rome, but it was no use. “The poor man, who is crazy, takes the surest means of losing everything,” scoffed Archbishop Napoléon-Joseph Perché to another bishop.

Borias later expressed regret for his “violent and offensive words.” His apology was received. In a letter to Borias, Perché thanked God for having inspired Borias with “more Christian and priestly sentiments than had been evident in recent days.”

What was the reason for the dispute? Records aren’t definitive. Yet while Borias wasn’t the fighter that Claude Maistre had been, the next years at Sacred Heart as well as in Borias’s career suggest the conflict might have resulted from a stand against the Church’s near-total abandonment of interracial worship during the advent of Jim Crow legislation. Before long, Borias’s former church in New Orleans would look nothing like it did when he served as pastor. According to Roger Baudier’s 1939 history The Catholic Church in Louisiana, “In 1881, Archbishop [Napoléon-Joseph] Perché appointed Father Célestin Frain and under his administration of 35 years, the colored societies disbanded and the church had a white congregation.”

With their pastor gone and church organizations disbanding, the Herrimans returned to St. Augustine Church, presumably along with other Creoles of color. At least one Black parishioner remained, however. In 1913, the Daily Picayune reported on the death of a woman named Aunt Annie Morris in Charity Hospital, who said she was 115 years old. Whatever her actual age, she had attended Mass daily at Sacred Heart, near her home on North Robertson Street.Besides noting Antoine Borias’s offensive language to his superiors and his appeals to Rome, Catholic Church records don’t indicate how Antoine Borias might have tried to stop the dismantling of Sacred Heart as a church for Black Catholics. But it does record his next request: In 1881, he wrote to Archbishop Perché after hearing that a church in Breaux Bridge might be looking for a priest, following the departure of its pastor, Father Ernest Forge. Borias made clear the reason for his interest: He had been told “there are many well-disposed Negroes there who would be good Christians if the priest occupied himself.”

Borias would not be immediately sent to Breaux Bridge. His first stop was in Brusly in West Baton Rouge Parish, to serve at St. John the Baptist Church. The church was still reeling from a recent scandal, with charges and countercharges over failed leadership, as well as threats of excommunication. It all ended when the church’s pastor stole away with a parish woman to be married in New Orleans. Borias would serve in Brusly for five years of relative calm. He is most remembered for having blessed a bronze church bell in 1888, giving it the name “Marie.”

In 1888, Borias’s wish to go to Breaux Bridge was granted. For the next twelve years at his new post in St. Bernard Church, Borias seemed indefatigable. He embarked on a flurry of construction projects, expanding the church and building a new rectory. And within three years of arriving, he brought in nine members of the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration to establish schools for both whites and Blacks. Within the first year, 135 African American children were reportedly among those educated.

Segregation was the order of the day; these were not interracial schools. Yet the dangers of Borias’s project were underscored when, at the same time, just fifteen miles away in Arnaudville, a new school with Black students was visited by a group of masked vigilantes known as the “Regulators,” who showed up on the first day of school to intimidate children and their teachers. Several days later, the school was set afire.

There are no records of similar acts of violence against the schools Borias helped establish in Breaux Bridge. Yet he did encounter resistance to his plans. Although details are not known, Borias reportedly tried—and failed—to establish a Catholic church for Black parishioners in Breaux Bridge during this time.

Through it all, Borias remained a popular local figure. An Easter Sunday Mass in 1891 drew a thousand worshippers, according to a letter to a local newspaper whose author added that “Father Borias may feel proud of the house of God of which he is pastor.” When, on April 28, 1900, Borias passed away after being in ill health for the previous year, “Breaux Bridge was thrown into mourning,” the Daily Picayune reported. Sixteen hundred mourners filled the church. Nine priests led the services, with local bands and the church choir. All businesses shut down for an hour that day.

In 1990, the Breaux Bridge Historical Society inducted Borias into its Hall of Fame. Yet though his position as a pioneering priest is well known, much of his work remains a mystery. Borias both succeeded and failed at addressing segregation during his lifetime. The subject would remain explosive for both society and churches.Borias’s legacy includes the career of Jules Jeanmard, a former altar boy who served for Borias and was educated in Borias’s schools. Jeanmard would become Louisiana’s first native-born bishop, and the first bishop of the Diocese of Lafayette. He welcomed the diocese’s first Black priests and made national news in 1955 when he excommunicated two women who had assaulted a teacher for giving religious instruction to an integrated class.

Within a year of that incident, Jeanmard resigned. The excommunication of the two women was lifted. But the integrated classes continued. It was a century after Antoine Borias first arrived in Louisiana and fifty-five years after his death. Yet Borias’s project of reconciling race and his faith has remained unfinished.

Michael Tisserand is a New Orleans–based writer whose most recent book, George Herriman: A Life in Black and White, was a 2018 Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Book of the Year. His website is www.michaeltisserand.com.