Ursuline Convent

The old Ursuline Convent remains as the only French colonial structure in the French Quarter known to have survived the fires of 1788 and 1794 and one of the oldest buildings in the Mississippi Valley.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

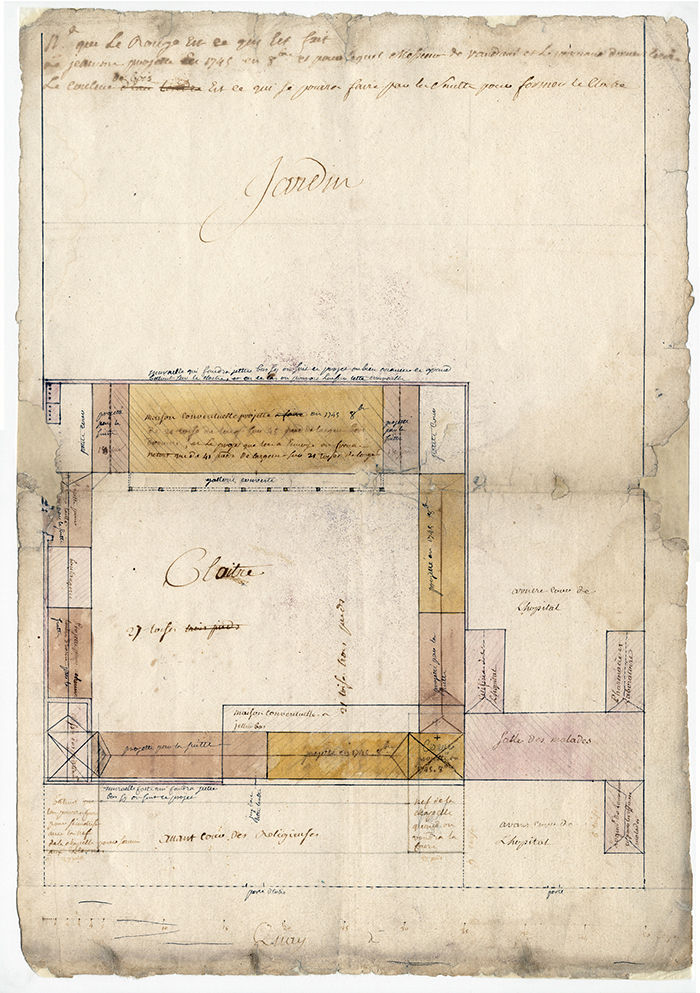

Plan for Ursullines Convent. Broutin, Ignace François (Draftsman)

The Ursuline Convent remains as the only French colonial structure in the French Quarter known to have survived the fires of 1788 and 1794; it is one of the oldest buildings in the Mississippi Valley. Today this national landmark, which also served as residence for Catholic bishops and archbishops between 1824 and 1899, comprises part of the Archbishop Antoine Blanc Memorial, named in honor of the New Orleans Archdiocese’s fourth bishop and first archbishop. In addition to the convent, the complex includes St. Mary’s Catholic Church (1845) and several secondary buildings constructed by the nuns and bishops. A significant loss to this religious site was the 1985 demolition of wall remnants from the Almonester Chapel (1786).

The Ursuline Nuns and Their First Convent (1734–1752)

In 1727, only a few years after the settlement was founded, twelve Ursuline nuns arrived in New Orleans from Rouen, France. Their mission, as stated in the 1726 treaty between the Ursulines and the Company of the Indies, was “to relieve the poor sick and provide at the same time for the education of young girls.” For their first seven years in the colony, the nuns lived in temporary quarters while awaiting the completion of the first convent, located in the lower French Quarter on part of an extensive royal land grant to the order. In 1727, the nuns’ property consisted of the equivalent of three squares, located between today’s Decatur, Royal, Ursulines, and Governor Nicholls Streets. The nuns moved into their home in 1734.

The design of the early structures on the nuns’ grounds is documented in a series of finely executed plans and elevations by royal engineer Ignace Francois Broutin, preserved in the French Archives Nationales. By 1745, however, the first convent was collapsing. According to architect-historian Samuel Wilson Jr., Broutin’s original plans were modified and the colombage (brick-between-posts) construction was left exposed, precipitating decay in the southern Louisiana climate.

The Second Ursuline Convent (1752–1824)

Although Broutin’s drawings for the second convent date from 1745, the building was not completed until 1752. Significantly, when the new building was constructed—just behind the old convent—the monumental floating cypress stairway with wrought iron railings was removed from the first convent and installed in the second. Also preserved from the first convent is the lead plate from the cornerstone. Interestingly, for years no one seemed to know that an earlier convent preceded the existing one. As far back as 1815, Jacques Tanesse’s Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans depicted the existing convent, dated incorrectly to 1733. Even the stained glass fanlight windows (1889–1890) in the Chartres elevation entry portico mistakenly give the construction date as 1730–1734. Not until Wilson located the drawings for both the first and second convents in the Paris Archives in 1938 did this knowledge become widespread.

Inspired by the plans of French military engineers, published in the eighteenth century, the design of the surviving convent—in the Louis XV style—emphasizes the building’s French origins. Dominated by central pedimented bays outlined with quoins on both the river (originally front) and Chartres elevations, the building has a high pitched roof, flared slightly at the edges and pierced by a series of dormers. Unlike the earlier half-timbered building, the second convent has solid masonry construction (stucco over brick). Of the many secondary buildings constructed by the nuns, only the kitchen building on the river side of the convent remains. A second story was added to this originally one-story structure.

Despite the nuns’ anxiety during the Spanish takeover in 1763 and the transfer to the United States in 1803, they retained their property rights under the new governments. The final challenge, however, came from the local city council, which voted in 1819 to extend Condé (Chartres) and Hospital (Governor Nicholls) Streets through part of the nuns’ property. With the interruption of their cloistered privacy, the nuns purchased a site two miles downriver and constructed their third, now demolished, convent.

The Bishopric and Archbishopric (1824–1899)

After they moved, the nuns donated the second convent and its surrounding grounds to the bishop of New Orleans, and extensive changes were made during the early years of the bishopric. In addition to providing lodging, a portion of the convent was converted into a short-lived school. A new portico was added to the Chartres elevation, transforming the entrance from the riverside. The existing gate lodge was constructed on the Chartres elevation in 1824, and a new entrance was made on the Ursulines’ side elevation. This door led into the bishop’s private living quarters. Later modifications include the ca. 1850 construction of the bishop’s service building (originally a one-story structure) on the Ursulines’ side of the property. The Chartres entry portico was modified to its present appearance in the 1890s by architect James Freret, and its stained glass lunette windows date from the same time.

Almonester Chapel (1786) and St. Mary’s Italian School (1870)

On the river side of the convent, running along Ursulines Street, stood a small building, erected in 1786 as a chapel at the bequest of Don Andres Almonester y Roxas. A number of period sources, including Jacque Tanesse’s 1817 map of New Orleans, depict this one-story building. After the 1794 fire destroyed the St. Louis Church (now known as St. Louis Cathedral), it served as parish church for a while. After construction of St. Mary’s Catholic Church in 1845, the chapel ceased to be used for religious services. In 1870 a seminary was opened on the site, and lower walls were added to the old chapel. The building operated as St. Mary’s School or St. Mary’s School for Italians from the late nineteenth century until 1964, when the building was deemed structurally unsafe. The upper walls were demolished in the early 1970s, and in 1985 the historic lower walls were demolished without Vieux Carré Commission approval.

St. Mary’s Catholic Church (1845)

In 1845, the French-born architect J. N. B. DePouilly, also responsible for the 1850 remodeling of St. Louis Cathedral, designed a new church to replace the old chapel. His austere, classical building was known first as the Bishops’ Church and later, after the influx of Italians into the Quarter in the late 1800s, as St. Mary’s Italian Church. In the 1970s it was called Our Lady of Victory Church. Today, the name has returned to St. Mary’s. Constructed on the downriver side of the convent, the church actually encroached upon the northeast end of the old building. A 1919 extension of the sanctuary further impacted the convent’s original fabric.

Decline and Rescue

After the archbishop’s residence moved to Esplanade Avenue in 1899, the convent continued to be used as ecclesiastical offices and later as rectory for St. Mary’s Italian Church. The complex, which served the Quarter’s Italian immigrant residents, gradually fell into disrepair. With the rekindled interest in the Quarter in the 1930s, the importance of the old convent was recognized. In the 1930s, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) documented the convent’s historic features. In the 1965 Vieux Carré survey, the old convent complex was identified as in need of major repair.

In response to community concern, Archbishop Philip Hannan appointed a committee to “study and recommend measures to preserve the old Ursulines convent” in 1966. Around the same time, Wilson and his architectural partner Richard Koch made a model for the restoration of the complex, including reconstruction of the Almonester Chapel. In the early 1970s, Mayor Maurice Edwin “Moon” Landrieu took the position that a public body should control the convent in order to develop the site as a “historical monument rather than church-oriented property.” In 1973 the archdiocese undertook restoration of the convent and its outbuildings.

The proposed renovation raised a philosophical question: Should the renovation include preservation of changes over time or restoration to the 1745 appearance? For an answer, the Vieux Carré Commission turned to the community’s architects and historians. The approach followed was to retain the ca. 1890 Chartres elevation portico and standardize millwork features, using the HABS drawings for guidance. Other minor renovations have taken place over the years, all the while maintaining the integrity of this French colonial landmark, which today serves as a museum documenting the lasting relationship between the religious institution and the community.