“A Very Nice Lady”

The Chris Owens legacy

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

The Historic New Orleans Collection

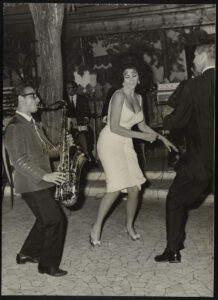

Chris and Sol Owens, at right, dance at an unknown club in the 1950s.

Two months after her death a sale of her estate was announced. Fans and relic hunters rejoiced. Consignment and estate-sale service the Occasional Wife held a three-day sale of items from her home and club, and Neal Auction Company featured treasures from her closets, jewelry boxes, and private rooms at several sales. The offerings included furniture in an array of styles, from Louis XV armchairs to a glass coffee table with a bronze sculpture of a woman as the base; photographs of Owens with celebrities such as Muhammad Ali; and custom outfits and costumes worn by the performer, including a number of colorful fur jackets and several of her iconic Easter ensembles.

Before the estate was made available to the public, The Historic New Orleans Collection was able to preview some of the offerings and purchase a select few. The group contains a white fur stole, two posters, and nine photographs of Owens. Together these pieces create a cohesive collection representing a giant of New Orleans entertainment.

Chris Owens was born Christine Joetta Shaw on October 5, 1932, in Stamford, a small West Texas town. One of eight children, she grew up on a farm and ranch and studied nursing at Texas Wesleyan College before moving to New Orleans at the age of 20, joining her eldest sister there. While working as a medical receptionist, Shaw met local car dealer and impresario Sol Owens. They married in 1956.

The couple opened a nightclub, Club 809, at 809 St. Louis Street, just off Bourbon. Within a few years, the club was thriving, largely because of the couple’s charisma. Chris and Sol dominated the dance floor, showing off Latin moves they learned at the famed Tropicana club in Havana, Cuba.

“We’d go [dancing] every night,” Owens said in her 2014 oral history for THNOC. Bandleader Xavier Cugat “would shine a light on us, and so then people would . . . just get off the floor when we’d start to dance Latin music. And just by [continuing] doing it and going to Havana and going to all the famous watering places around the country, that really highlighted my career.”

It’s difficult to overstate the explosive popularity of Latin music and dance styles in mid-1950s America. Perez Prado was “King of the Mambo”; Dean Martin’s “Papa Loves Mambo” was a huge hit; and I Love Lucy was bringing Cuban music into millions of people’s homes every week. With her beauty and skill, Owens became a face of the trend, appearing in the Saturday Evening Post and the syndicated column of New York gossip reporter Walter Winchell.

“I’ll never forget that night,” Owens said, in her oral history, of the time she first met Winchell. She was at the New York City nightclub El Morocco. Actor Jackie Gleason was at a table, and when Winchell asked Owens to dance, he sidled them up to the star, saying, “‘You’ve got to watch this girl, watch this girl do the mambo.’

“Then, nobody was really moving their bodies. People would really dance kind of stiff, but I was going to Havana then and dancing the way they did in Havana. That’s what really started it all off.”

Meetings with Hollywood producers and engagements at other famous venues followed. With Chris’s glamour-girl image ascendant, the couple parlayed that success into a full stage act for Chris at Club 809.

“Sol was my manager, so I left everything up to him,” Owens said. “They [Hollywood producers] said, ‘Oh, my god, we’re offering you more than now what we’re paying Jayne Mansfield, Marilyn Monroe.’ And I said, ‘No, it’s up to him.’ Sol said, ‘No, we just bought our club,’ and so we stayed in New Orleans.”

In 1968 the couple purchased property across the intersection from Club 809, at 500 Bourbon, creating a larger venue on the ground floor and maintaining their own residence and rental units upstairs. Her cha-chas and mambos, backed by a troupe of “Maraca Girls,” became the hit of Bourbon Street, putting her on par with Al Hirt and Pete Fountain. As Owens liked to say, her act attracted the “crème de la crème”—local notables as well as visiting celebrities. “Every major legendary star in Hollywood would be brought in by friends when they’d come to town,” she said.

In 1976 the Owenses dropped the old 809 moniker to name the club after its star. It remained the Chris Owens Club ever after.

The success of her act hinged partially on audience engagement. In the early years Owens would pass around maracas and conga drums, encouraging spectators to feel the rhythm. As her act progressed, she would bring people up on stage, getting them to dance and declaring them “hot.”

After her husband died, in 1979, Owens took over ownership of the club and the apartments above, where she resided for decades. In 1983 she became the “grand duchess” of the French Quarter Easter Parade, known for the elaborate bonnets worn by celebrants. Owens kept this honor for the rest of her life, typically parading with her longtime companion, Mark Davison, until his death in 2019. She continued performing at her eponymous club until the COVID-19 pandemic stopped live performances. Two weeks before the 2022 Easter parade, she passed away, on April 5.

The posters purchased from Owens’s estate include one listing the performances at the Chris Owens Club during the 1990 Super Bowl weekend and another from the 1991 Carnival season, when Owens reigned as queen of the Krewe of Tucks alongside New Orleans coroner and trumpet player Dr. Frank Minyard. Through the estate sale, THNOC was connected to Owens’s niece, who donated an additional group of objects documenting the entertainer’s career. The donation consists of percussion instruments from Club 809, photographs, music records, and several community awards, including one from Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee bestowing upon her the title “A Very Nice Lady.”