Bourbon Street

The origins of the notorious adult playground

The Historic New Orleans Collection

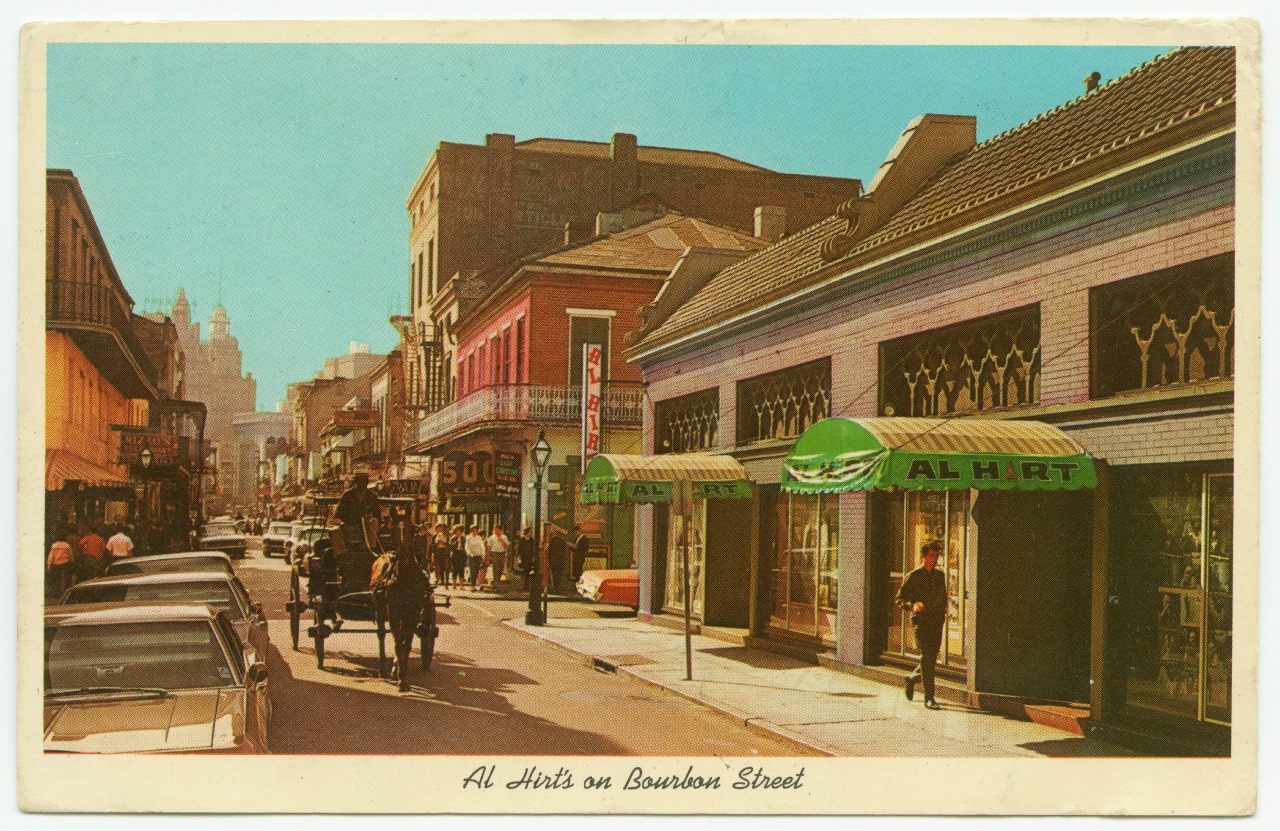

Postcard of Al Hirt's music club, 1970.

Geographically, Bourbon Street is a fifteen-block-long street in downtown New Orleans. Historically, it is one of the city’s twenty oldest streets. Economically, it is 55 percent commercial and 45 percent residential. Administratively, it lies 93 percent in the French Quarter (Vieux Carré), 85 percent within Vieux Carré Commission jurisdiction, and 80 percent within the original plat of the French colonial city of Nouvelle Orléans. Culturally, it hosts a boozy adult entertainment district that since the 1940s has earned both national fame and local infamy. To its proponents, Bourbon Street celebrates and sells New Orleans culture, creating thousands of jobs and forming the epicenter of the city’s tourism economy. To its detractors, it symbolizes superficial indulgence and crass consumption that stigmatizes the city.

Origins

Quite different was the case in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. French engineers first surveyed Rue Bourbon into the banks of the lower Mississippi River in 1722 and named it to honor members of the reigning house of France. Settlers built West Indian–style houses along this and other streets of the village-like settlement, and Rue Bourbon became home to a rather intermediary demographic during the French (1718–1762) and Spanish (1762–1800/1803) colonial eras. Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, probably built in the 1770s and still operating as a tavern today, generally reflects the street’s long-destroyed eighteenth-century building stock.

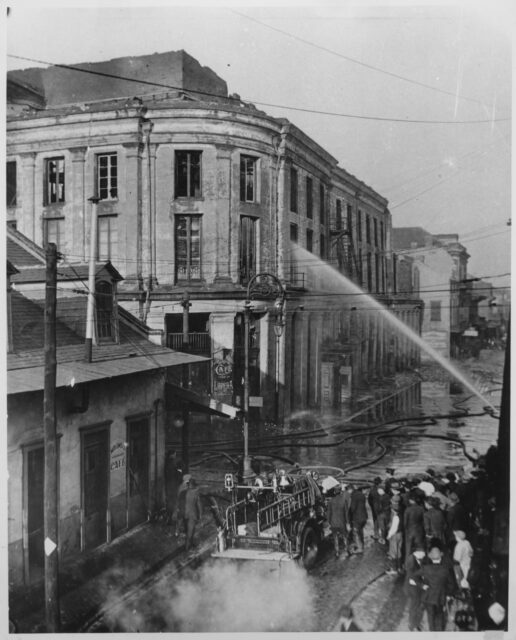

Nearly half of the French Creole edifices on Calle de Borbón (as the Spanish called it) were destroyed in the Good Friday Fire of 1788. Following a subsequent blaze in 1794, new building codes brought forth a more urban Spanish-style streetscape. This architectural form was “creolized” (that is, adapted to local conditions) after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, when the region fell under the domain of the United States. Perhaps the best example of this early-nineteenth-century modified Spanish Colonial style is the circa 1806 Old Absinthe House at 240 Bourbon, also a bar today.

Bourbon Street in the antebellum era (1803–1861) continued its relatively prosaic status, even as New Orleans rose in population and prominence. The street in this era was neither particularly powerful nor disenfranchised, neither bustling nor sleepy, and not at all notorious. It was, rather, a reasonably priced place for light commerce and home-making among the working and middle class, with smaller numbers of poorer and wealthier families as well.

Antebellum Bourbon Street did, however, have some distinctions. Its first block became the address of this Catholic city’s first Protestant house of worship, and later a Jewish synagogue. Two-thirds of Bourbon’s Jewish families had addresses on its Anglo-dominant first block. The remainder of the street comprised mostly Francophone Creoles who were either white, gens de couleur libre (free people of color), or Black and enslaved, in addition to immigrants primarily from the Caribbean and Mediterranean regions.

Another distinction arrived in 1859 with the construction of the French Opera House. This grand performance venue plus nearby theaters stoked the twilight bustle and gave entrepreneurs an opportunity to serve patrons with food, drink, lodging, and diversions. Thus was planted one of the seeds from which, decades later, the modern Bourbon Street entertainment scene would germinate.

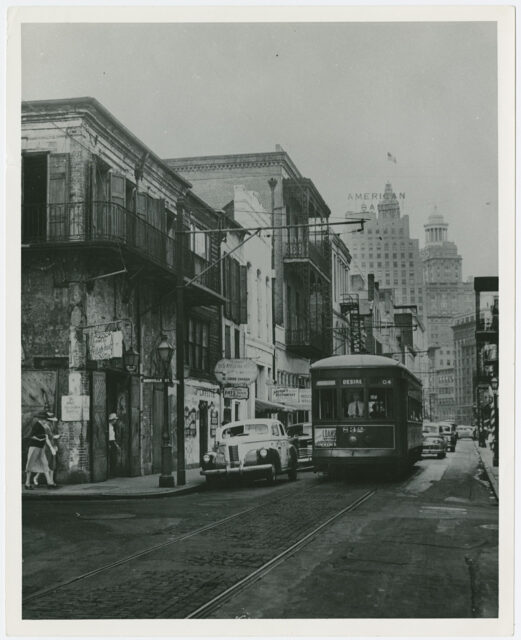

Desire streetcar at Iberville, ca. 1940s. Charles L. Franck Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Emergence of an Entertainment District

American cities changed after the Civil War, and New Orleans was no exception. The metropolis’s inner core grew congested, industrialized, raffish, and less appealing as a place to live. Wealthy Creoles moved out, replaced by poor immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, particularly Sicily. Geographies of indulgence and vice shifted correspondingly: formerly prevalent in the urban fringe, the saloon and gambling scene now flourished in the central city, where, starting in the late 1860s, a new innovation appeared: the concert saloon.

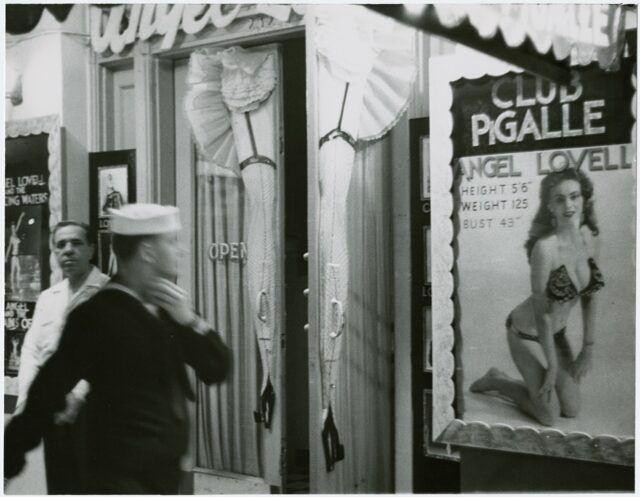

Featuring sexualized performances such as the can-can dance, concert saloons catered to men on the town via copious amounts of alcohol served by attractive young waitresses. A concert saloon named Wenger’s opened on Bourbon Street in 1868, becoming the first venue offering the type of entertainment for which Bourbon would later become famous.

Americans by this time were increasingly venturing out to see their country. Industrialization had helped raise the ranks of the middle class, and families had more disposable income to spend on leisure travel. New railroads made once-arduous journeys swift and comfortable, and new parks and resorts presented enticing destinations. Fancy hotels were built to accommodate the new tourists, and fine restaurants turned “eating out” into entertainment. The “local color” literary genre in vogue at the time depicted places like New Orleans as quaint and exotic, and made people curious to visit. New Orleans, for its part, aimed to draw visitors with attractions like the 1885 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in present-day Audubon Park.

City officials, meanwhile, noted the widespread distribution of vice downtown, particularly the sex trade, and worried about its impact on the city’s reputation. In 1897, a councilman named Sidney Story crafted an ordinance forbidding prostitution from all areas except sixteen contiguous blocks behind the French Quarter, where, by default, it became legal. A later amendment forced concert saloons and other sexually themed venues to locate nowhere else but the aforementioned space, which came to be known as Storyville.

Businesses of the upper French Quarter reeled from the shift of nocturnal entertainment to Storyville. But it would not remain there for long. A violent “Tenderloin War” broke out in 1913, which made Storyville’s reputation all the more odious. When the US joined World War I, the Navy, worried about the health of its sailors, succeeded in getting Storyville closed.

Storyville’s demise shifted the vice and entertainment scene back into the French Quarter, specifically around Rampart and Burgundy at Iberville, an area known as the Tango Belt. Vice raids in the 1910s–1920s, plus commercial encroachment from Canal Street, led to the Tango Belt’s demise.

The Development of Nightclubs

It was at this point, during Prohibition, that Bourbon Street gained a key advantage in the nighttime entertainment scene. On January 13, 1926, a French-born restaurateur named Count Arnaud Cazenave, owner of an eatery on Bienville at Bourbon, opened The Maxime, at 300 Bourbon, which he modeled on an innovation he had first seen in Paris—a “night club.”

Unlike in concert saloons, an air of exclusivity circulated in nightclubs. Restaurant service made nightclubs a total-evening experience, and patrons danced, as most arrived as couples, quite different from the male-dominated scene of concert saloons. Nightclubs catered to the liberated lifestyles to which women in the 1920s were laying claim; here was a place you could bring a girlfriend or wife and feel safe, entertained, and exclusive.

The nocturnal appearance of “decent” middle-class women in the 1920s helped re-gender a space that had previously been mostly male and decidedly sketchy, a change that laid the groundwork for large-scale middle-class tourism. After Prohibition, and despite the Depression, Bourbon Street had attracted roughly three dozen clubs and bars. It was locally noted as a fancy nightspot, but all but unknown nationally.

All that changed when World War II broke out, and millions of servicemen and war plant workers found themselves crossing paths in New Orleans. To Bourbon Street’s clubs and bars they gravitated, and by 1945, Bourbon Street had become big, raucous, lucrative, notorious, and nationally famous.

Over the next twenty years, capacious burlesque clubs with elaborate shows and renowned entertainers operated door-to-door with bars and fancy restaurants. There was a little Chinatown on the 500 block, and while renters lived in the garrets, working-class folks mostly of Sicilian or Creole descent lived in the residential blocks downriver. Until 1949, the Desire streetcar line, made famous in the eponymous play by Tennessee Williams (who once lived around the corner), ran down the entire length of Bourbon to Desire Street.

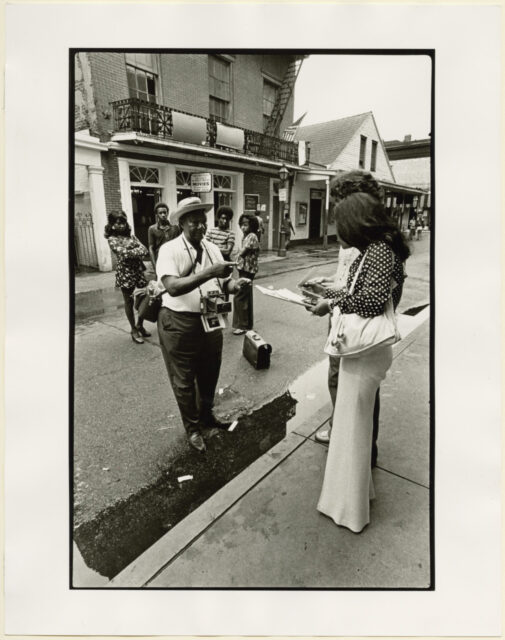

Itinerant photographer on Bourbon Street, 1978. Photo by Josephine Sacabo, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Vice and Corruption, Reform, and Mass Tourism

Bourbon Street during this “golden age” had, however, its share of problems. Many clubs made high profits only because organized crime ran extensive illegal gambling operations in the backrooms, and padded their profits with exploitive “B-drinking” schemes, in which dancers would sucker a “mark” into buying her overpriced drinks. Drunk tourists were routinely “rolled” in back alleys, and naïve country girls originally hired as “B-girls” or dancers often found themselves pulled into Bourbon Street’s sex trade. Residents of the French Quarter, which was gradually gentrifying in this era, bitterly fought Bourbon bar owners over vice, noise, signage, litter, architectural transgressions, and other flashpoints. Like the rest of New Orleans and the South, Bourbon Street was also strictly segregated, and was pointedly unfriendly to African Americans in any role except that of entertainer or laborer.

Bourbon Street changed dramatically in the 1960s. Modern jet travel and new corporate hotels brought mass tourism directly to the street’s doorsteps. Most significantly, the newly elected district attorney Jim Garrison, aiming to appeal to voters with a reformist anti-vice crusade, calculated that burlesque clubs were costly operations with big staffs and could only turn a profit if they ran illicit activities on the side. By cracking down on the illegal but lucrative activities in the back of Bourbon Street clubs, Garrison made the legal but costly main attraction untenable. Clubs closed left and right during 1962–1964, and were gradually replaced by tawdry joints and junk shops whose operating costs were low enough to turn a profit. Hippies and rubes started to outnumber couples on fancy dates, and businesses repositioned themselves accordingly.

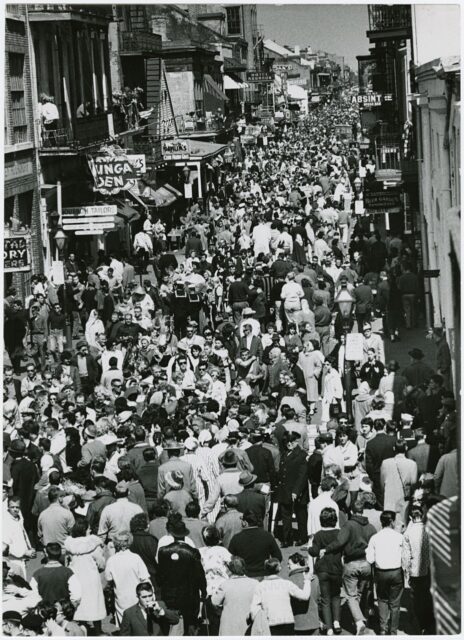

The decline of the traditional burlesque scene meant that visitors increasingly strolled up and down the street past the clubs and bars, even as barkers cajoled them to enter. In 1967, one enterprise came up with a better idea: instead of convincing people outside to buy drinks inside, why not sell inside drinks to people outside? One by one, bars and clubs opened tiny window or alleyway outlets through which they sold beer, drinks, hot dogs, and snacks directly to pedestrians. The go-cup was born, and it would soon completely rewire the social and economic dynamics of Bourbon Street. Whereas historically the action was in the exclusive private space of the clubs, now it shifted to the passing parade of pedestrians in the street. For this reason, nearly all businesses on Bourbon today (except, by law, the strip clubs) throw open their doors, blurring the line between public and private space and allowing money to flow from outdoors to indoors. “Window hawking,” as it was called, created a nonstop pedestrian parade, and brought litter and public intoxication to what had previously been a stylish destination. To New Orleanians, Bourbon Street by the early 1970s had become a carnivalesque embarrassment.

Zoning Enforcement and Debates

Mayor Moon Landrieu knew something had to be done, and to that end, formed the Bourbon Street Task Force in 1976. A model of civic reform, the task force conducted extensive research and devised a series of new policies. To remedy spot zoning and nonconforming uses, it devised a new Vieux Carré Entertainment zone. To remedy unsightly signage, it forged a formula determining its size and position. To remedy the low grades users gave to shopping on Bourbon Street, it advocated the removal of outdoor T-shirt displays. To remedy tax cheating, it clarified and enforced which enterprises were “bars” as opposed to “restaurants.” To remedy the nightly transition to a pedestrian mall, it designed a system of portable bollards. To remedy littering, it increased and coordinated trash collection. To remedy the lack of organization, it formed the Bourbon Street Merchants Association. Perhaps the task force’s wisest decision concerned what not to remedy. It succeeded because it knew just when to let Bourbon Street be Bourbon Street, and just when to not.

On account of the task force reforms and the ensuring prosperity of the 1980s–1990s, Bourbon Street recovered from its 1960s–1970s nadir, and reinvented itself with a sort of beachy tropicality theme aimed at the spring-break college student set. Since then, Bourbon Street has been relatively stable; a walk down the street today is remarkably similar to the experience fifteen or thirty years ago. By no means, however, is it at peace with its neighbors. Bourbon business owners and residents routinely engage in protracted political and legal battles over noise abatement and other issues, and parties on both sides are apt to describe the situation as “worse than ever,” despite that they’ve been going on consistently for the better part of a century.

Many New Orleanians side with the neighborhood residents and openly express disdain for Bourbon Street. But there is no arguing with its commercial success. Bourbon Street has a nearly hundred-fold greater job density than the rest of the city, and among the highest property values. It constitutes the main attraction for the city’s roughly ten million annual visitors. Anywhere from twelve to twenty thousand people pack the street’s eight commercial blocks at any given moment on Mardi Gras, scenes of which are broadcast worldwide—free publicity for Bourbon Street, and a source of wistful dismay for its critics.

What detractors may not recognize is that Bourbon Street is largely a product of deep-rooted localism. The dizzying deafening artifact we see today originated organically, without an inventor (such as Jazz Fest) or a vision (the World’s Fairs of 1885 and 1984) or a legislative act (Storyville). There is no Bourbon Street logo, no headquarters, no board of directors, no visitors’ center, no brochure, not even an official website. The nightlife that made the street famous—after two hundred years of utter normalcy—was created spontaneously by a cast of working-class characters who, in an uncoordinated attempt to make a living individually, succeeded collectively.