Magazine

Alexandria’s Hotel Bentley

A Gilded Age hotel in Central Louisiana has a storied history

Published: December 3, 2014

Last Updated: January 30, 2019

Courtesy of Louisiana State University Libraries, Special Collections.

This color postcard shows the lobby of Alexandria's Hotel Bentley in 1912.

When the Bentley was built, Alexandria was booming. As the center of Louisiana’s pine lumber industry, dozens of sawmills operated within a 50-mile radius and more than 20 passenger trains came through the city daily. In this hive of activity, lumber baron and entrepreneur Joseph A. Bentley saw his opportunity. He would build a splendid hotel to outclass everything between Shreveport and New Orleans.

To design his hotel, Bentley turned to sought-after architect, George R. Mann of Little Rock, Arkansas. Mann had begun his career in the New York City architectural office of McKim, Mead and White, the most influential design firm in the nation. The firm popularized a type of classically-inspired and symmetrically-planned architecture that was based on the curriculum of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris; Charles F. McKim had studied there. Mann’s own designs reflected that influence.

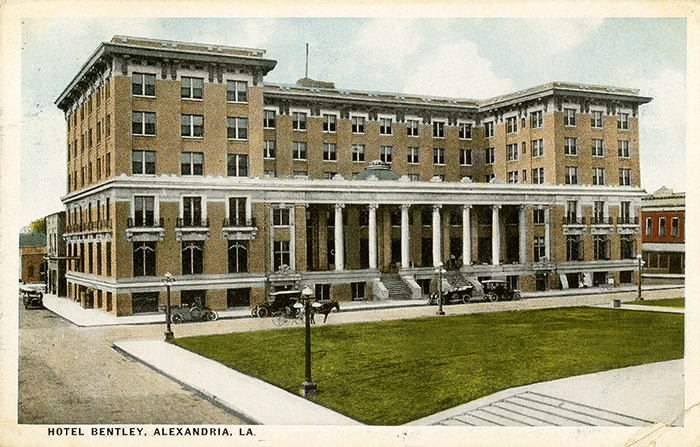

This color relief halftone postcard of the Hotel Bentley in Alexandria was postmarked 1920. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

The Bentley hotel fills the entire block on DeSoto Street and is raised on a half-basement, which gives its six upper stories additional height and presence. It is a symmetrical three-part composition with a recessed central section flanked by identical wings. The smooth buff-colored walls are enlivened by elaborate window lintels and belt courses in a lighter-colored Bedford limestone. A tall cornice and extended eaves give the hotel a strong conclusion. The most striking exterior feature is the row of seven two-story high Ionic columns that fronts the hotel’s central section and which is crowned with a tall entablature and cresting. The design was described at the time as modern French Renaissance.

George Mann’s three-part scheme for the Bentley echoes such works by McKim, Mead and White as the Villard House group (1885) in New York City or Rosecliff (1902), the ocean-front villa in Newport, Rhode Island. A formal symmetry became favored for homes of the wealthy at the turn-of-the-20th-century. Rosecliff also has an Ionic colonnade fronting its recessed central section. Such deliberate echoes of opulent and ultra-fashionable residences allowed the Bentley’s visitors to feel that they too were entering a palatial mansion.

Two wide flights of marble stairs rise to the Ionic columns and a loggia, and from there through double doors to the magnificent 100-foot long lobby that stretches out to left and right. Grand lobbies were an essential component of hotels and the Bentley’s has all the requisite elements. Its double-height space is framed by marbleized Ionic piers that rise through a mezzanine level to the coffered ceiling. A confection of ornamental plaster moldings and scrolled and paired brackets adorns the ceiling. In its center is a shallow dome with an oculus and, because the dome is invisible outside at street level, it appears all the more as a surprise.

Originally the interior surface of the dome was painted by Romanian immigrant Herman Sachs with cartouches and swags, imagery that added an imperial flavor to the lobby. The dome’s surface was repainted in the 1990s with a pastoral scene by artist Nicholas Crowell of New Orleans. The lobby also boasted a fountain and fish pond in which, reputedly, Joseph Bentley kept bass. In the center of the lobby, a grand staircase leads up to a mezzanine that runs the entire length of the space. From here guests could observe the comings and goings of those in the lobby below.

The Bentley’s features—“marble” columns, tile floors, overwrought ornament, chandeliers, and surfaces that gleam and glitter—marked the new luxuries of urban hotels. The goal was to create atmosphere and inspire memories.

For overnight guests, the rooms had every modern amenity of their day. Bathrooms and toilets were on each floor and bedrooms were provided with a bowl and pitcher for washing. The hotel also included a honeymoon suite with its own parlor. And Bentley himself maintained an apartment in his hotel.

As well as offering all the conveniences that every traveler expected, the Bentley became a center for fashionable town gatherings. An opulent luxury marked the formal dining room with its coffered ceiling and forest of columns, and the glamorous Venetian room served as a ballroom. The hotel also included a café, barber shop, cigar stand, parlors, writing room, stenographer and telegraph offices, and a billiard room. In the early part of the last century, large hotels served as the premier business and social space of a city, forming a new type of privately held public space.

The Bentley’s design meshed with early-20th century “City Beautiful” planning schemes. The great colonnaded entrance dramatizes and gives superb definition to the street and the building’s classical dress complemented the (now demolished) domed and columned city hall that sat opposite. The Bentley gave monumentality to the city center, and it still does.

George Mann (1856-1939) went on to design other buildings in Louisiana. In Shreveport his marvelous Old Commercial National Bank (1911) drips with the kind of ornamentation found in the Bentley’s great lobby, and his high-rise Slattery Building (1924) is a fashionable interpretation of Modern Gothic. Mann had a flair for the splendid as is evident in the bathhouses he designed in Hot Springs, Arkansas, such as the Fordyce and the Arlington. There he included domed spaces like that of the Bentley’s lobby.

In the 1930s, Joseph Bentley decided to enlarge the hotel and an eight-story extension was added in 1937 to the hotel’s rear. Given that the nation was in the throes of the Great Depression, Bentley’s decision seemed irrational at best, but it turned out to be prescient. Alexandria was about to enter another boom, this time brought on by the United States’ entrance into World War II. The city became a center for five military bases and businesses moved in to serve the troops. Such notables as Omar Bradley, George Patton, and Dwight Eisenhower stayed at the hotel, as did visiting officials and families of military personnel.

In the 1940s Alexandria became a hub for military bases, justifying Joseph Bentley’s addition of an eight story extension to his namesake hotel. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

In much larger cities and those that can host major conventions, many historic hotels have found a new life catering to people seeking the architectural grandeur of the Gilded Age. But for majestic hotels in smaller cities that lack the critical mass of guests, these splendid buildings often languish. Although renovated with modernized bedrooms in 1985, the hotel closed in 2004.

Yet the Bentley should find a new life and reclaim its place as Alexandria’s focal point. With tax credits for renovating and reusing historic structures, it could be converted into a multi-purpose building, accommodating, for example, city offices, some hotel rooms, and perhaps a few condominiums. The Bentley, now 101 years old, counts as one the most handsome of Louisiana’s historic hotels.

——–

Update: As of January 2019, the Bentley now houses a hotel and condos.

Karen Kingsley, Ph.D., is professor emerita of architecture at Tulane University, author of Buildings of Louisiana (2003, Oxford University Press), and a freelance writer.