Magazine

“They Call Me Baby Doll”

The resurrection of a Mardi Gras tradition

Published: February 4, 2015

Last Updated: February 19, 2019

Photo by Andy Levin.

Antoinette K-Doe, left, resurrected a Baby Dolls club in 2003.

Editor’s Note: As part of a yearlong partnership between Louisiana Cultural Vistas and WWNO 89.9 FM, New Orleans’ NPR affiliate, broadcast journalist Eve Abrams is interviewing past contributors the magazine. The following feature story by Xavier University Associate Dean Kim Marie Vaz appeared in the Winter 2010 edition of Louisiana Cultural Vistas. Vaz went on in 2013 to write the book The “Baby Dolls”: Breaking the Race and Gender Barriers of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Tradition (Louisiana State University Press). The radio program, which will delve into Vaz’s research on the African American Carnival tradition of masking as “baby dolls,” aired on February 4 during Morning Edition and can be heard at the link below.

“Sure, they call me Baby Doll

That’s my name.

I am a Baby Doll today and every day.”

—oral history from Gumbo Ya Ya:

A Collection of Louisiana Folk Tales by Lyle Saxon

Seven-year-old Miriam Batiste was bursting with excitement as she saw the Baby Dolls turn onto the 1300 block of St. Phillip Street one Fat Tuesday or “Old Fools Day” as Mardi Gras was called in her Treme neighborhood in 1930s-era New Orleans. The Baby Dolls she saw were a group of mostly women, accompanied a man or two, dressed to the nines in shiny, colorful satin short dresses, with bonnets, bloomers, and Mary Jane shoes, accessorized with lollipops and screen masks covering their faces, or a satin mask with a piece of cloth covering their mouths.

The men who costumed alongside these women wore satin pants and hats in the same color as the Baby Doll dresses. The women hand-crafted all of the costuming except for the screen masks which were purchased in the French Quarter. The Golden Slipper Club, led by Miriam’s very own mother, Alma Trepagnier Batiste, masked annually in red, yellow, green, pink, or blue satin and began their parade very early in the morning initially calling themselves “The Dirty Dozen.”

Ms. Miriam, as she is affectionately known, recalled that “The Dirty Dozen was the nickname for how the older people would come out. Some men wore union drawers or thermal suits—all-in-ones with flaps in the back. They would wipe cha-cha, relish mix with mustard, or peanut butter, on their bottoms.” But mostly, the men liked to dress in women’s clothes and bonnets. Alma Batiste would dress in pink bloomers and an apple smock, fishnet stockings, and a pair of black baby-doll shoes. The group went from house to house where they received a little “recess” of food and drink. “There was one house they would return to and dress in their pretty costumes,” Miriam said. The Golden Slipper Club’s Baby Dolls were accompanied by Miriam’s father, Walter Batiste, who played the guitar and her brothers and other relatives who made up the Dirty Dozen Kazoo Band.

The Baby Dolls were one of the numerous social aid and pleasure clubs that could be found in New Orleans African-American neighborhoods. Like other clubs, they participated in the second-line tradition of dancing, singing and chanting while accompanying a brass band on public streets in a display of collective identity.

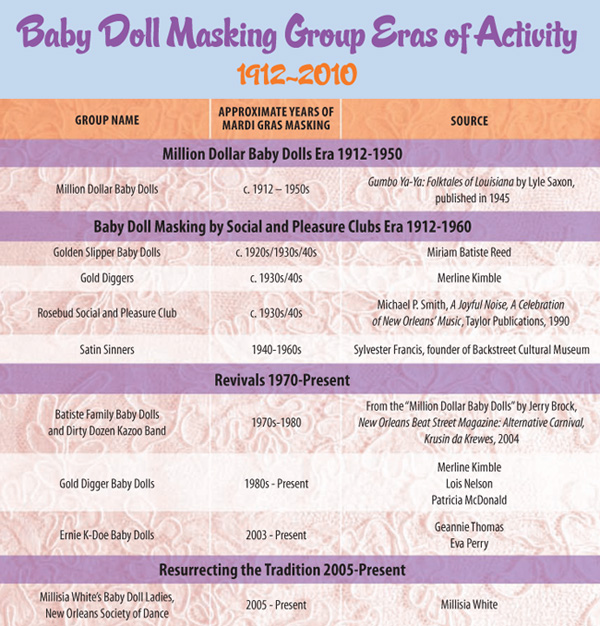

Up through the mid-20th century many neighborhoods had their own groups of Baby Dolls. The tradition became dormant as the maskers aged, passed away and other opportunities for participating in Carnival activities increased.

Up through the mid-20th century many neighborhoods had their own groups of Baby Dolls. The tradition became dormant as the maskers aged, passed away and other opportunities for participating in Carnival activities increased.

Fast forward, 20 years and it is the 1950s. The late Antoinette K-Doe who owned the “Mother-in-Law” Lounge on Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans, is a child, looking in awe at the Baby Dolls on a Carnival day and just assuming that she can play with them. Her grandmother tells her, “Those ladies are grown-ups.” She is impressed with these women who seem so independent and full of fun. As an adult, Antoinette will bring the Baby Doll tradition back in a real big way.

A group of Baby Dolls masking in the early 20th century. Courtesy of Louisiana State Library.

Revivals

Miriam, her sister Felicia and her brothers began masking and marching in the Baby Doll tradition again in the 1970s. When Felicia died, a big jazz funeral was held in her honor and Miriam attired a mannequin in the deceased’s Baby Doll dress, bonnet, and socks. “My sister was laid out at Charbonnet’s funeral home and that mannequin was standing at the head of her casket.” Felicia’s costume is now on display at the Backstreet Cultural Museum in New Orleans.

A decade later, Merline Kimble and Lois Nelson borrowed the name of Merline’s grandparents’ old social aid and pleasure club, The Gold Diggers. Merline remembered that “they came out the 1400 block of Dumaine before the sun would come out. They would come out with the band consisting mostly of my grandmother, Louise Recasner Phillips’, 13 brothers and sisters. They would go around the Sixth Ward from bar to bar drinking just like the previous generation.” The Gold Digger men wore tuxedos and top hats and the women wore satin Baby Doll dresses.

To make her grandmother happy, Merline hit upon the idea to bring back the Gold Diggers Baby Dolls. “When my grandmother was old, she had nothing to look forward to. . When all the Baby Dolls walked in the house, my grandma’s face lit up. That’s all she talked about.” Like other groups, the Gold Diggers wore brightly colored costumes in an era when men generally only wore dark tuxedos. The women got together and made yellow, green, and orange tuxedos and dyed the hats.

When Merline and her friends paraded as the Gold Digger Baby Dolls, they debuted at Merline’s mother’s house on Ursuline Ave. “We put plywood down in the driveway and Walter ‘Wolfman’ Washington set up his whole band to play for the Baby Dolls for no pay, on Carnival Day!,” she said. Then the Gold Diggers accompanied the Rebirth Brass Band on the big stage at Claiborne and Orleans Avenue. Today they mask primarily on Mardi Gras and for the Satchmo SummerFest second line Parade.

Socially, much was happening at the advent of Baby Doll masking in 1912. Jazz was evolving from the music hall to the street. Women were rebelling against Victorian restrictions.

The origins of the Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls, named in honor of Antoinette’s late husband, the legendary, rhythm and blues musician Ernie K-Doe, dates to 2003 according to co-founder, Geannie Thomas. Antoinette noticed that the “Chief of Chiefs” of the Mardi Gras Indian tribes, Allison “Tootie” Montana, was not among the murals of Indians on the columns of the interstate along Claiborne Ave., the historic gathering place and the current site of African-American masking on Mardi Gras day. Antoinette asked the Montanas if she could have Joyce and Tootie’s portraits painted on the outside of her lounge which is adjacent to the elevated interstate. Antoinette then remembered that historically the Baby Dolls marched with the Indians and decided to revive the tradition. Geannie found it especially memorable that the K-Doe Dolls were able to reconnect to that masking heritage. Their group of Baby Dolls grew to about 40 and “marched with Tootie, because not long after that he dropped dead fighting for the Indians’ gathering under the bridge” while testifying in New Orleans City Council chambers.

The founding members of the Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls were Antoinette, Geannie, who owns a commercial cleaning service called Do It Right, Not Twice, and Eva Louis Perry, owner of Tee-Eva’s Famous Pies and Pralines. They called on Ms. Miriam to learn the history and costuming practices. They have marched and performed with her at numerous venues from nursing homes to clubs. The Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls have put their own unique spin on the work of a social aid and pleasure club. They are devoted to community service, such as feeding the homeless at Thanksgiving with the sheriff of Orleans Parish, in addition to their commitment to their craft as entertainers, dancers, character actors, and back-up singers for notables such as Al “Carnival Time” Johnson.

The Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls’ charitable works know no bounds. They were pallbearers for Lloyd Washington, one of the last living singers of the Ink Spots. His family’s limited funds prevented them from burying his ashes. Antoinette had kept his ashes in the lounge for months until a burial place could be found for them. Geannie decorated her red Dodge Dakota truck with greenery and used their stage prop casket to transport the ashes as they marched from St. Augustine Catholic Church to St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.

A New Generation

Imagine now that it is Mardi Gras in the 1980s and Millisia White, founder of the New Orleans Society of Dance Incorporated’s Baby Doll Ladies, is about ten years old and is ready to run out to the street to celebrate. “I grew up the Sixth Ward, “ says Millisia. “My vague remembrance of the Baby Dolls was with the Skeletons. That’s who first came out to announce Mardi Gras. It took you into this world. I remember the Baby Dolls just coming through the neighborhood. I asked my grandmother, ‘Who is that? Can I get out there and dance?’” She said, “No, that’s Baby Dolls; that’s women.”

Millisia never forgot about the Baby Dolls and when she formed the New Orleans Society of Dance, Inc., the Baby Dolls became the symbol of her organization. “It is typical for a dance company to have a face or a theme that they tie in. We tie in themes from practices from back in the day, our birthright. We borrow from the idea and contribute to the idea. We want do the tradition justice. With the blessing of past generations, we cultivate it, upgrade it and bring it to 2010. Every neighborhood had a group of Baby Dolls. It was womanhood personified. We can show it the way it has never been seen.”

Those in Millisia’s group are the newest generation to pick up the Baby Doll mantle. They do so with the blessing and guidance of Miriam Batiste Reed. As fellow member Davieione Fairley notes, Baby Dolls are “no generation. We represent our ancestors, those that danced before. We are bringing it back with flavor and choreography. Baby Dolls used to be in the back of the Zulu parade and today we march in the front.”

“Men would put money in their garters. The women made sure that their dresses were short enough for the men to see the garter and the men knew what that meant.” —Eva Perry

The Baby Doll Ladies continue the chanting tradition while they parade and practice, which resembles the Mardi Gras Indian call and response tradition. Millisia noted that “The Baby Dolls always chanted. I remember them with homemade tambourines and a small band. They would sing and dance, just like when they were in church … they would second line.”

Millisia has updated the music by featuring “bounce,” New Orleans’ underground music, the city’s vernacular of hip hop. DJ Hektik, who performs with the company, laid tracks under the group’s signature and ribald chant, Fire in their Drawers.

“When we perform, we incorporate the tambourine and the cowbell and upgrade it with bounce,” says Millisia. “It is a way for us to introduce it to the new generation.”

Millisia’s NOSD is part of what she and DJ Hektik have coined “The Resurrection.” The goal is to serve as an example of hope after the city’s devastating setback by Hurricane Katrina. When all seemed lost, Millisia and Hektik brainstormed about how they could reconnect New Orleans’ African Americans with their heritage. “We wanted to resurrect the things that unified us, what makes New Orleans unique.” Resurrecting the Baby Dolls, a tradition that was largely dormant among young people before Katrina, became Millisia’s contribution to the city’s recovery. Millisia decided to showcase Creole dance and share it with the world through choreographed stage performances and videography.

Eddie “Duke” Edwards, jazz musician and executive director of the Louis Armstrong Foundation in New Orleans, whose Aunt Vanilla was a Baby Doll and who wrote the signature chant for the Baby Doll Ladies, noted that the Baby Dolls are known for having an attitude. “Their spirits are high and they are free in their minds” he said. “They know who they are and what they are. If they can be accused of anything, it is too much pride and knowing too much.”

Storyville District Origins

Socially, much was happening at the advent of Baby Doll masking in the 1910s. Jazz was evolving from the music hall to the street. Women were rebelling against Victorian restrictions on their self-determination and sexuality. Women, who were not associated with the notorious red-light Storyville district, mimicked those who were on Mardi Gras day.

Eva Perry of the Ernie K-Doe Dolls described the start of Baby Doll masking: “They would have flouncy clothes on that were very short: bloomers, lace stocking and garters on their legs. Back then, they were really hustlers. That’s what the Baby Dolls were. They went out to make money on a Mardi Gras Day. That’s why they went out early, because they knew people were coming out to see the Indians and the Skullheads that went out before the Indians. Men would put money in their garters. The women made sure that their dresses were short enough for the men to see the garter and the men knew what that meant.”

Lois Nelson, a member of the Gold Diggers and a former nightclub owner recalled that the Baby Dolls in Storyville named themselves the Million Dollar Baby Dolls and hustling for them was a way of life, not just a Mardi Gras day event.

Alma Trepagnier married Walter Batiste in 1909 and she became the mother of a large family. She took in laundry to help support her children. Miriam and another sibling would often be dispatched to pick up and return the clothes of the customers, some of whom were prostitutes in the District. “We were never allowed to pass Basin Street; that’s where the train tracks came around near the Krauss Building and Iberville. That was the District [i.e. Storyville]. Young girls were not allowed there. One of the ladies brought my mama her clothes to wash. They didn’t want to send them to the laundry to mess them up. Mama would put their clothes in a basket and me and my brother or me and my sister would walk to Basin Street. One of the ladies would come out, take the basket of clothes and give us the money.”

We may never know, but it is not inconceivable that two women from different walks of life, connected by gender, race, and the need to earn an income, living in close proximity because of the racial segregation of the times, shared a love for clothes, beauty, costuming, and artistic expression. It is not unimaginable that during conversations over laundry on a Basin Street corner, or in the privacy of the sewing room, that each would take one bright idea and develop it in her own way.

The Baby Dolls continue to stir the imagination. Geannie Thomas recalled the first year they marched many people approached the members saying that they remembered the Baby Dolls. “When we came down Canal Street people were so happy to see that the Baby Dolls were back.” It was the joy on their faces that moved Geannie. As she marched by she children say, “That’s a Baby Doll!” Mama, who is that Baby Doll?”

———

Kim Vaz Deville, Ph.D., is Associate Dean in the College of Arts and Sciences at Xavier University in New Orleans.